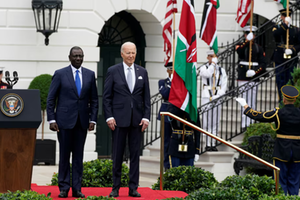

Kenya President William Ruto and US President Joe Biden during their talks at White house on May 23, 2024.

Kenya is now America’s closest military and, potentially, economic ally in Sub-Saharan Africa after the announcement of various agreements and negotiations during President William Ruto’s State visit to the United States.

This comes hot on the heels of decisions by West African nations – long under the heel of the French – invited their erstwhile masters to bugger off, and take their American friends with them. France has lost its footing in Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, even in Gabon where its man Omar Bongo, the father of recently deposed and confined Ali Bongo Ondimba, ‘ate’ his country with the master.

Most of the West African countries have mineral resources and will develop, particularly without French exploitation. But Kenya, and most of East Africa, without minerals worth a dime and having destroyed its agricultural production through mismanagement and political sabotage, will have to take a more circuitous route, one that relies on creating a stable, peaceful and open environment for commerce and striking smart alliances that improve competitiveness.

In the fullness of time, Kenya will almost certainly become America’s proxy in regional conflicts, there will be US troops on Kenyan soil, America will meddle in Kenyan affairs and gain access, sometimes to the disadvantage of locals, to the Kenyan market. But, if negotiations are handled well, they will help Kenya survive and prosper. The biggest risk is conflict, whether internal or in close proximity.

Al Shabaab terrorism from Somalia has set Kenya’s development many decades: The cost of fighting wars and therefore diverting resources from productive use, the impact on tourism especially at the Coast, the undermining of development in Northern Kenya where government workers from other parts of the country were targeted and either killed or chased away, the shooting of university students and security – all these have put a damper on economic progress. The capacity to deter or deal with conflict is a paramount imperative for the future.

Sudan conflict

Looking around the region, Kenya appears to be sitting in a ring of fire consisting of countries which are already on fire and others which are stable but have the potential to encounter unpleasant events. Kenya is itself only one bad election away from a serious meltdown as happened in 2007.

Sudan conflict is the worst of all regional wars: The 300,000-man national army, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) led by General al-Burhan, is facing off with the 100,000 strong RSF, former Janjaweed, well equipped and stationed in Khartoum and Darfur, its stronghold. By April, nearly 16,000 people, including military personnel, had been killed, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). However, ACLED and experts have said those numbers are a significant undercount, due to the difficulty in collecting accurate, real-time data during a conflict of this nature.

A report by the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, in October last year estimated that nearly 4,000 civilians were dead and 8,400 injured in Darfur alone, between April 15 and the end of August. Reuters quoted a UN report in January claiming that between 10,000 and 15,000 people had been killed in just one city – El Geneina, in Sudan’s West Darfur region – last year. Whatever the case, thousands are dead and the country basically destroyed. RSF supply lines and resources, although their fighting capabilities remain substantial, with a steady inflow of arms and personnel.

Some 25 million, 14 million of them children, need help; 8.6 million have been displaced from their homes, 6.6 million being IDPs and while 1.8 million have fled to Central African Republic, Chad, Egypt, Ethiopia, and South Sudan.

Ethiopia, where the guns are silent after the war with TPLF two years ago, is peaceful but unstable. The Tigrayans threw in the towel when they realised they were going to be wiped out by the combined armies of Eritrea and Ethiopia as well as armies from other regions of the country.

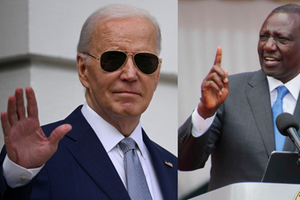

U.S. President Joe Biden welcomes Kenyan President William Ruto during an official White House State Arrival ceremony on the South Lawn of the White House in Washington, U.S., May 23, 2024.

President William Ruto addresses a press conference at the White House with US President Joe Biden on May 23, 2024.

The lasting impact of that war, according to some analysts, is a country whose central government exists at the mercy of provincial armies – it looks stable from far but is far from it. Ethiopia is a nation of about 125 million, generally mobile and migratory people. According to the International Organisation for Migration, about 840,000 Ethiopians migrated to other countries in search of jobs and a better life. Ethiopians can send the region reeling by migration alone.

Political stability

Tanzania is the most placid and peaceful country in East Africa and takes great pride in its political stability. Recently, a Tanzanian minister attributed the country’s stability to its “political heritage”, a reference to moderate, civil and restrained approach to politics. Tanzania is also a very image-conscious society, rarely airing its dirt in public and always committed to making a good impression and presenting the nation in good light. But “political heritage” also involves enforcement of astounding firmness: When the government decided to evict Maasai herders from Loliondo in Ngorongoro wildlife area and move them 600 kilometres to Msomera, it was not done with flowers and chocolate.

It involved force, the alleged seizure or killing of 6,000 animals and $2.5 million in fines, according to The EastAfrican, quoting the pastoralists. Elections in Tanzania are often a lively affair, especially in the independent-minded islands of Zanzibar and Pemba, where there are claims of ballot rigging and electoral violence of fantastical proportions. Human Rights Watch, for example, accused the Tanzanian authorities of serious human rights violations in Zanzibar during the 2020 election.

The watchdog said “state security forces, alongside a government-aligned militia, patrolled the streets of … Zanzibar, beating and harassing residents, firing teargas, and shooting at people indiscriminately. The security forces also broke into people’s homes, and arbitrarily arrested opposition supporters, detaining and torturing them for weeks”. Since independence in 1964, every election has been returning Chama Cha Mapinduzi with a regularity and certainty somewhat at variance with political dynamics and realities on the ground – a sometimes strong opposition and national yearning for change. The magma of secession and religious radicalisation churns beneath feet of the Tanzanian state and it is credit to law enforcement that they have sustained peace and stability in the face of it.

In September 2017, Tundu Lissu, 52, Chadema leader and vocal critic of the government of then President John Pombe Magufuli who was expected to run for president in 2020 was shot 16 times in Dodoma. That he survived to tell the story is perhaps testament to the tough constitution of Tanzanian men. But Magufuli, a blunt tyrant, went at CMM’s hallowed structures and mores like the grim reaper, imposing his will and subverting political tradition in a surprisingly disruptive manner. After his death, the transition was anything but smooth.

It was said that some wise guys from his inner circle decided that the constitution was subordinate to their superior wisdom, that then Vice President Samia Suluhu Hassan couldn’t cope with the rigours of power and were looking for someone more suited for the job from amongst their number to take up the mantle. They were thwarted, eventually, and the constitution obeyed. But the lesson was learnt that “political heritage” will ensure calm and stability only to the extent that crazyheads like Magufuli are kept a mile from power.

Strange political alliance

In Uganda, President Yoweri Museveni, the Methuselah of African Big Men, 38 years in power and counting, wields absolute authority from atop a strange political alliance – his family – which works together to subdue and rule Uganda. Being a wise politician, Museveni is without a declared or assumed successor. He knows that the minute the successor emerges, he will lose power – courtiers will transfer their allegiance and love to the coming man or woman.

Museveni has ruled Uganda through a combination of guile, revolutionary humbug, droning speeches peppered with old, outdated economic concepts – if lectures could develop a country, Uganda would have a GNI per capita higher than Lichtenstein’s $$165,287 – and a practiced application of sheer violence and terror on the population and his opponents. Mr Kizza Besigye, the opposition leader, is routinely denied the right to leave his house, or even walk the streets, in this ‘democracy’. But, analysts suspect, Museveni’s longevity owes a lot to his deft use of his family, which is not a family in the traditional sense, but an alliance of politically powerful individuals.

Mama Janet Museveni is a wily political operator in her own right and the President embraces her not just because of her great beauty but because she brings complementary political value. His son, Gen Muhoozi Kainerugaba is rumoured to be a little lacking in sobriety and gravitas, but he is a political mobiliser of some ability. And he couldn’t have spent his whole life in the military without assembling a following. He launched a noisy campaign to succeed his father which grew legs and captured the attention of the youth. His father scotched the succession campaign by appointing him the Chief of Defence Forces of the Uganda People's Defence Forces: he killed his political ambitions by hogtying him with military discipline. Gen Muhoozi can’t send a drunken tweet, call a political rally or go galivanting in Rwanda any more. His political ambitions are on ice.

Operation Wealth Creation

But it is the man who installed him as CDF – Museveni did not – the President’s younger brother Gen Salim Saleh, who is Museveni’s most valued mid-fielder, clearing the field and feeding him the ball upfront. Well-liked and effective, Gen Saleh heads a big organisation – Operation Wealth Creation - with a large budget and massive national reach. Analysts regard him as perhaps the most networked individual in Uganda. The question is: Without a successor in sight, would this alliance hold Uganda together and keep power, if Museveni were to be otherwise unavailable to exercise it, whether by stepping down or incapacitation? Or will it descend into chaos and splinter into regional fiefdoms?

Congo is a strange land where the government rejects its own people, terming them foreigners and, using the lure of gold, uses foreign forces to subdue the citizens it oppresses and, with a level of incompetence with few peers in a generally badly run continent, mismanages the great wealth and resources of the country. The big question is not whether DRC will pull itself together – that is highly unlikely – but whether it will suck Africa into a continental war for its gold. At the moment, members of the East African Community are on different sides of a war that also draws in powers such as South Africa and Angola.

Ancient grievances

In Rwanda, the icy focus of RPF has developed the country and brought stability and unity to a land previously torn apart by ancient grievances, culminating in the slaughter of 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu by Hutu hardliners 1994. Some of these hardliners are in DRC and given a chance would regroup and return perhaps for a second go at genocide. President Paul Kagame is likely running for his last term and so long as he is in charge, Rwanda will prosper and be peaceful. The question is: has he and the RPF healed Rwanda’s ancient sores and will his successor continue down the same path of development and stability or will conflict and disaffection return to haunt the tiny nation.

Somalia is a basket case, a nation in a state of collapse for 30 years. Its problems of terrorism, war and corruption have become self-sustaining and endemic, a part of the country’s anarchic DNA. Diplomacy, expansionist dreams, business and rudimentary human services continue to be offered in an environment of state collapse. A generation that has known nothing but war came of age a decade ago. Conflict and contestation are the normal state of affairs. The idea of a peaceful, prosperous Somalia is possibly a pipedream, further complicated by Gulf and Arab power games being played in its territory.

The government of Hassan Sheikh Mohamud excited the world with its claims of fighting and defeating Al Shabaab. The truth of the matter is that with the exception of small slivers controlled by ATMIS and the government, the rest of Somalia is outright controlled by Al Shabaab, or is contested. “Writing is on the wall for HSM (Hassan Sheikh Mohamud) administration – without ATMIS, Somalia falls to Al Shabaab,” wrote Horn of Africa expert Rashid Abdi on X. And is the reality for East Africa: A Somalia controlled by Taliban-style government exporting terrorism, expansionism, smuggled goods and population to the region, especially Kenya.

Tribalism

At the heart of the ring of fire, Kenya itself is always an election away from total collapse. Democratic institutions are smothered by tribalism, dictatorship, corruption, economic gangsterism and weak rule of law. If Tanzania is help together by CCM’s mastery of survival and statecraft, Kenya stays together out of luck and occasional neo-colonial and imperialist intervention.

The deals with America have the potential to strengthen capacity to deal with conflict but also shore up democracy and the effectiveness of the state. But this alone cannot deliver the bacon: a competitive economy requires good infrastructure. The $3.6 billion (about Sh471 billion) agreement between Kenya Highways Authority(KenHA) and the little known US infrastructure investment manager Everstrong Capital clears the way for the construction of a 440 km (273 miles) highway between Nairobi and Mombasa.

The Expressway will be financed through a public-private partnership (PPP) model, with funding structured as 70 per cent debt and 30 per cent equity. Under a 30-year concession, Everstrong Capital LLC will manage the entire lifecycle of the Mombasa Expressway, from construction to tolling and maintenance. The project is not a new idea, it was first mooted in a 2018 Oval Office meeting between retired president Uhuru Kenyatta and former US president Donald Trump.

The highway, which was supposed to cost Sh318 billion at that time, was to be built by Bechtel, the notorious US company popularised by its reconstruction work in Iraq after the war. Kenya felt it didn’t have headroom for more loans and wanted Bechtel to build the road with its own money and recover it by levying tolls.

Bechtel refused, arguing that the Public Private Partnership (PPP) model would have increased the project’s cost to Sh1.5 trillion. Kenya struck a deal with Korean Overseas Infrastructure and Urban Development Corporation Africa (KID) to undertake the project. However, after taking power, the Ruto administration went slow on the project, finally chucking out the Koreans in favour of the Americans.

The most serious issues to consider regarding the project are three: One, whether there is demand for a project of this nature, especially one funded by debt at a time when the country is mortged to the ears; where there is actually any demand for more capacity for the Nairobi-Mombasa route, given that there is a new and very expensive railway there; and, finally, once you have transported cargo by road from Mombasa and dumped it in Nairobi, then what?

Mombasa port

In 2023, the port of Mombasa handled 35.98 million metric tonnes of cargo, of which only six million metric tonnes was hauled by rail. The other 29 million metric tonnes or so was transported by road which means even if you were to triple the share of cargo by rail, there would still be a lot of capacity left for road. The heaviest user of Mombasa port is Uganda, accounting for 85 per cent of transit cargo. The fact that SGR which would be cheaper than road does not deliver from port to user in one run is a major disadvantage at the moment.

Competitiveness also requires smart trade partnerships. Kenya and the US are negotiating a deal under their Strategic Trade and Investment Partnership (STIP), started under the Jubilee administration and which the government wants done by October. Negotiations cover agriculture, anti-corruption, digital trade, environment and climate change action, and workers’ rights and protections. This will be the first significant trade partnership between the US and a country in sub-Saharan Africa. Countries in the region currently rely on the African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa), which offers duty-and-quota-free access to the US market. The new deal is seen as a model for future agreements between the US and other sub-Saharan African countries.

The US says the “goal of the STIP is to increase investment; promote sustainable and inclusive economic growth; benefit workers, consumers, and businesses (including micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises); and support African regional economic integration” which would be a game-changer for Kenya but of course the devil is in the detail. It’s a good start, with lots of work pending.