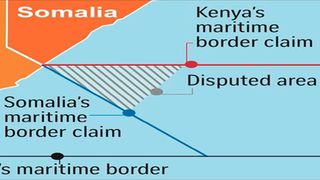

The Kenya-Somalia maritime border.

| Joe Ngari | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

Kenya’s options in Indian Ocean border row with Somalia

The International Court of Justice’s hearings on the boundary dispute between Kenya and Somalia continue without Nairobi’s participation, with Mogadishu set to exploit a legal provision to capitalise on the one-sided proceedings.

According to the statute establishing the ICJ, failure by one party to appear does not prevent the proceedings from taking their course, rather, it opens a window for the participating party to press for a judgment in its favour in the absence of the defendant.

The only caveat is that the court must first satisfy itself that it has jurisdiction.

“Whenever one of the parties does not appear before the court, or fails to defend its case, the other party may call upon the court to decide in favour of its claim,” states Article 53 of the statute.

“The court must, before doing so, satisfy itself, not only that it has jurisdiction in accordance with Articles 36 and 37, but also that the claim is well founded in fact and law,” it adds.

President Uhuru Kenyatta with Somali President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmaajo, during his inauguration ceremony in Mogadishu, Somalia.

Given the court has previously rejected Kenya’s application that contended the court lacked jurisdiction to arbitrate the dispute, it would appear the caveat contemplated does not arise.

Kenya has several options going forward. One step the Kenyan government has signalled is to lodge a protest with the United Nations Security Council, where Nairobi took over a non-permanent seat in January.

Kenya’s position has been that the two neighbouring countries have expressly agreed on a method of settlement other than the court for delimitation of their maritime boundary.

Nairobi has cited the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Kenya and the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia signed on April 7, 2009, in which both parties committed to a negotiated agreement rather than recourse to the court.

Somalia’s action to move to court in 2014, Kenya has argued, is in plain violation of its obligations under the MoU to negotiate an agreement following Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) review.

According to the MoU, Kenya states, the two countries were to only delimit the full extent of their maritime boundary after recommendations by the CLCS on the establishment of the outer limits of the continental shelf.

Kenyan authorities have vowed to circulate their protest to all diplomats, suggesting a campaign to discredit ongoing proceedings and pressure the world court to drop the case.

The hope is that the diplomatic offensive could yield either one of two outcomes.

According to the world court’s operations, a case may be brought to a conclusion at any stage of the proceedings by a settlement between the parties or by discontinuance.

In case of discontinuance, an applicant state may at any time inform the court that it does not wish to continue the proceedings, or the two parties may declare that they have agreed to withdraw the case. The court then removes the case from its list.

If attempts to stall the proceedings at this stage aren’t successful, after the ongoing oral proceedings, the court will deliberate in camera and then deliver its judgment at a public sitting.

The judgment is final, binding on the parties to a case and without appeal.

The only other recourse available after judgment is to apply for a review, which can only be allowed upon the discovery of a new fact. Kenya has insisted there is a missing map that would bolster its case and undermine Somalia’s claim.

Short of submitting new evidence “of such a nature as to be a decisive factor” to occasion a review of hostile judgment, the only other option for Kenya would be to resort to defiance and refusal to comply with the court order.

In 2018, the United States rejected the court’s order directing that sanctions against Iran should not impact humanitarian aid or civil aviation safety.

Tehran had convinced the judges that sanctions imposed by the administration of President Donald Trump violated the terms of a 1955 friendship treaty between the two countries.

And in 1986, the US had also attacked the court after it ruled America owed Nicaragua war reparations.

In the Nicaraguan case, the US chose not to submit itself to the court's jurisdiction.

The US then used its permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council to veto resolutions demanding it observe the Nicaragua ruling. The US has since been hostile to the court.

In Africa, a land and maritime boundary dispute between Cameroon and Nigeria over the Bakassi Peninsula and areas in the Lake Chad Basin was the subject of a long-running territorial dispute between the two nations.

Cameroon submitted the case unilaterally invoking the ICJ's jurisdiction and upon commencement of the case, Nigeria initially contested jurisdiction.

Like in the Kenya and Somalia row, Nigeria argued that both states had already agreed to settle the dispute through existing bilateral channels.

Nigeria later participated fully throughout the ICJ proceedings.

The ICJ's October 2002 judgment awarded Cameroon the Lake Chad boundary as well as the Bakassi Peninsula.

Nigeria, which won some maritime-related concessions, much of the boundary between Lake Chad and Bakassi, however, was reluctant to comply with sections of the judgment that didn’t go its way.

Faced with strong pressure from the international community, Nigeria at some point signalled the possibility of resorting to war, again, which saw world powers soften the hard line position that implementation of the ruling was not negotiable.

In the end, the international community asked Nigeria to “establish a dialogue with Cameroon to find a political way forward.”

Kenya hopes its grandstanding will, equally, pay off.

The Kenya-Somali row is high-stakes diplomacy, given the interest even among powerful nations around the oil-rich section in the disputed area in the Indian Ocean.

Kenya had downplayed the significance of Somalia’s protests until 2019 when the war-torn Horn of Africa nation put up for sale 15 oil blocks in offshore Indian Ocean.

The specific blocks offered for auction in London include Blocks 131, 142, 152 and 153 located in Galmudug and referred to as the Obbia Basin; Blocks 164, 165, 166, 177, 178 and 179 located in Hirshabelle referred to as the Coriole Basin; and Blocks 189, 190, 204, 218 and 219 located on the Jabu Lamu Basin, which is in Kenya's territorial waters.

A map showing Somalia and part of Kenya.

Had everything gone according to plan in the tendering for hydrocarbon exploration, Somalia had projected that by January last year, successful companies would have mobilised to start their exploration over four years.

The deal had an extension of two years and final renewal of another two years, after which the blocks were to revert to Somalia.

Each of the respective blocks measures 5,000 square kilometres.

And the border row has sucked in other players, given the quiet involvement of Tanzania since October 17, 2014.

In public documents submitted to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), Tanzania indicated that "Somalia is ready to enter into consultations with the United Republic of Tanzania with a view to reaching an agreement or understanding, which will allow the commission to consider and make recommendations on submissions by each of the two coastal states in the areas under dispute without prejudice to the final determination of the continental shelf to be concluded subsequently in the areas under dispute by the two coastal states."

Tanzania informed the CLCS in the same note verbale that the "Government of the United Republic of Tanzania is ready to engage into consultations on the overlapping area referred to in the executive summary of Somalia. Furthermore, communication to that effect has already been forwarded to the Permanent Mission of Somali Republic to the United Nations, with a view to commence negotiations regarding the said matter."

That is how what Kenyan officials initially dismissed as a storm in a tea cup that would be quietly calmed by the Office of the Attorney General and the Kenya International Boundaries Office (Kibo) has snowballed into a costly global crisis.