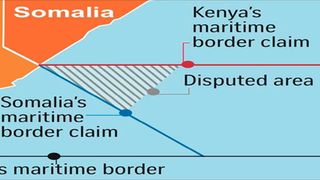

Kenya-Somalia maritime border.

| Joe Ngari | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

Shock as Kenya withdraws from Somalia border dispute case

Kenya will no longer participate in the international maritime boundary dispute case with Somalia in protest at perceived bias and unwillingness of the court to accommodate requests for delaying the hearings as a result of the pandemic, documents seen by the Nation show.

The bold move, relayed by Kenya to The Hague-based International Court of Justice (ICJ) ahead of the resumption of the case tomorrow (Monday), comes at a time of deteriorating diplomatic relations between Nairobi and Mogadishu and puts a big question mark on how any eventual decision will be enforced should the proceedings continue with only Somalia’s participation.

The court relies on the United Nations Security Council to ensure its decisions are respected but this is likely to present a diplomatic dilemma — depending on the outcome — as Kenya is currently a non-permanent member of the influential body where five of the world’s most powerful nations have permanent seats.

Territorial ownership claim

Somalia sent shockwaves across the region in 2014 when it filed a case at ICJ claiming territorial ownership of most of what is currently recognised as Kenyan waters in the Indian Ocean. Kenya has strongly defended its territorial integrity and dismissed arguments that, if upheld, could cause damaging socio-economic and political ramifications along the coastline.

The administration of embattled Somalia President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmaajo has in recent years taken a more aggressive approach towards President Uhuru Kenyatta’s government, accusing it of meddling in its internal affairs. Nairobi has repeatedly denied the accusations.

Attorney-General Kihara Kariuki communicated the government’s decision to the ICJ — also referred to as the World Court — on March 11, just days before the oral hearings were set to start on March 15 and run until March 24.

“Kenya wishes to inform the court, through the Registrar, that it shall not be participating in the hearings in the case herein, should the same proceed from March 15, 2021 as presently scheduled,” the letter by the Attorney-General states.

Kenya’s decision not to participate in further proceedings in this case, the letter to the court states, has been prompted by what Nairobi sees as bias by the court and the judges’ decision to press ahead with the oral hearings despite Kenya’s request for postponement to allow its team of new lawyers to familiarise itself with the matter.

The communication states that the Covid-19 pandemic means that Kenya has not been able to prepare adequately as it struck “just around the time that Kenya had recruited a new legal team”.

“The consequence of this is that Kenya and its legal team were deprived of the opportunity of having necessary preparatory meetings and engagements,” Mr Kariuki states in the letter, transmitted to the court through the Registrar, Philippe Gautier.

New lawyers

Kenya dismissed its legal team in 2019 over misgivings about the quality of representation and hired new lawyers in December the same year.

The new team is led by American professor Sean D Murphy and a former judge of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, Tullio Treves. Other members of the team are professors Phoebe Okowa — who is the only Kenyan member of the team but based in the UK — Makane Mbengue, Laurence Boisson De Chazournes, Christian Tams and Eran Sthoeger. The government also hired Coalter Lathrop to assist the team with geographic analysis and cartographic skills.

Moreover, the communication adds that as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, the country’s budget has been seriously impacted “with direct ramifications on Kenya’s ability to prepare for and defend the case”.

Kenya has also protested at the court’s adoption of virtual hearings, which Mr Kariuki says is “unsuitable for the hearing of a case as complex and as important as the present one”.

According to Mr Kariuki, Kenya’s case is largely based on demonstratives and cannot adequately and effectively be conducted by video link.

Despite what Kenya considers valid concerns, the government says the court has refused to consider its request to delay the hearings, compelling it to withdraw, which is “unprecedented in its history in relation to any international adjudication mechanism”, writes the Attorney-General.

“Since the case is not urgent for any reason, Kenya least expected that the court would make this into the first case to be heard on its merits via video link, despite one party’s sustained, well-grounded objections,” Kenya states.

The communication to the court further says that the continued participation of ICJ judge, Abdulqawi Ahmed Yusuf, a Somali national who as recently as February was the president of the court, does not promote confidence in the impartiality of the court. Yusuf was succeeded by American Joan E Donoghue as ICJ president in February but remains a judge of the court.

“Kenya’s concerns and perception of unfairness and injustice in this matter are exacerbated by the inexplicable rejection of Kenya’s preliminary objections to this court’s jurisdiction and the dismissal of the request for the recusal of Judge Abdulqawi Ahmed Yusuf, given his past exposure, on behalf of Somalia, to the issues in this case. This is notwithstanding the fact that Kenya has taken extensive measures that are illustrative of its good faith and seriousness in defending this case, including by filing pleadings within the timelines directed by the court,” the communication to the ICJ reads.

Nairobi had on November 16, 2017, sought the disqualification of judge Yusuf from the maritime boundary dispute. In the request, Kenya had cited the judge’s participation, on behalf of Somalia, in the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea.

“The said participation, Kenya asserted, made him privy to facts and evidence that are crucial in the case herein, and therefore placed him in a position of conflict of interest,” Kenya had told ICJ in an earlier communication of February 22.

No response

The government notes in the new letter that there has never been a response to the request for the judge’s recusal.

In communicating its decision to withdraw from the proceedings, Kenya has instead requested the court to allow its Attorney-General to address it for 30 minutes tomorrow (March 15) before the scheduled hearings start, to explain to the court what Kenya feels and also why it would not be participating in the proceedings.

According to the schedule for the public hearings that was published by the court on March 9, Somalia was to go first by making a presentation on Monday and Tuesday. Kenya was then scheduled to state its case on Thursday and Friday. Somalia would then go first again on Monday, March 22 for the second round of hearings and Kenya conclude on March 24.

Kenya has also submitted its position paper, a bulky document of about 180 pages, “for consideration by the judges even as the hearings proceed without Kenya’s participation”.

No enforcement mechanism

The ICJ lacks an enforcement mechanism for its decisions and relies on the UN Security Council to implement the rulings. Kenya began its two-year term as a member of the Council in January this year. It is the Security Council that will be charged with enforcing the decision of the ICJ in the matter. Kenya is also the current chair of the African Union Peace and Security Council (AUPSC), potentially giving it influence over the matter.

The battle for the 62,000 square-mile triangle in the Indian Ocean, which is believed to be rich in hydrocarbons, started in August 2014 when Somalia moved to the ICJ claiming that Kenya had violated its territorial integrity and should pay reparations, besides the anomaly being corrected in its favour.

Kenya filed a preliminary objection in October 2015 in which it questioned the ICJ’s jurisdiction over the matter given the existence of a 2009 Kenya and Somalia memorandum of understanding for resolving the maritime dispute out of court. Kenya also questioned the admissibility of the Somalia case. However, the court on February 2, 2017, rejected Kenya’s preliminary objections, paving the way for the hearing of the case.

The hearings had been set to commence on June 8, 2020 but were postponed to March 2021 “in light of the exceptional circumstances related to the Covid-19 pandemic”.

Before the decision to withdraw from the proceedings, Kenya had on February 22 submitted new evidence, including 315 pages of submissions explaining the nature and the relevance of new and additional evidence, and new documentation and annexes including maps and diagrams, among others. The Attorney-General had also requested for postponement.

In response to the submission of new evidence and the application for postponement, the ICJ Registrar Gautier on March 11 communicated the admission of the evidence except for one that Kenya was to produce during the hearing. However, the registrar’s communication was silent on the request to delay the hearings.

The Kenya-Somalia maritime dispute has seen world powers become involved, even if indirectly, attracted by the promise of abundant oil and gas deposits in the Indian Ocean waters. The US and France in particular have reportedly been siding with Kenya, driven by the partnership Washington, in particular, has with Kenya on the war on terror. Also, like France, the US could be interested the promise that American companies would benefit if Kenya controls the disputed zone.

On the other hand, Norway was one of the bidders at the Somalia Oil and Gas conference in London in February 2019. The conference was organised by Spectrum Geo Ltd, a Norway-based seismic data processing company which has been working with the Federal Government of Somalia.

The conference widened the diplomatic chasm between Kenya and Somalia after the latter recalled its ambassador to Mogadishu and also asked the Mogadishu representative in Nairobi to leave.