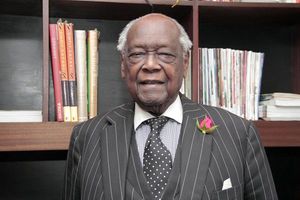

Former Attorney-General Charles Njonjo.

As Dorcas Oduor prepares to assume the role of Kenya’s Attorney-General, I am reminded of a confidential file I discovered at the Kew Archives in the United Kingdom. This document sheds light on the British disappointment regarding Charles Njonjo’s appointment as Kenya’s first African Attorney-General, though he later became their most useful ally. Given Njonjo’s British mannerisms, one might assume that he was always in London’s favour. That was not the case.

At one point, when Njonjo was still a student in London, the MI5 placed him under surveillance due to suspected socialist ties – a fact that surprised me when I stumbled upon the file. Njonjo once told me that "all university students were communists," though I doubt he knew he had an MI5 file. Moreover, I am unsure if he ever saw the confidential files in the UK bearing his name, which is a common occurrence. The situation began in July 1963 when Jomo Kenyatta, then Prime Minister, sought to appoint Njonjo as Attorney-General ahead of the Kampala conference, which was to discuss federalism.

In a Thursday, June 27, 1963 letter, Governor Malcolm MacDonald wrote to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, explaining that Kenyatta had told him it was "embarrassing to the (new) government that the Attorney-General should still be an expatriate since to some extent this inhibits ministers from seeking legal – and particularly Constitutional – advice".

The governor had hoped to receive a reply by Friday, June 28. However, the response from London came in the evening. It appears that Kenyatta was putting a lot of pressure on the governor.

"I waited until after lunch on Friday before seeing Kenyatta to inform him that I had agreed to his request and to clear with him a brief press statement which was issued that afternoon under embargo until Saturday morning," he noted.

Some reservations

By the time London sent its telegram with some reservations, the press statement had already been released. According to the governor, in his justification letter to London, he had postponed the appointment as long as it was practical and suggested "there would be difficulties if I don’t act now".

He proposed that Njonjo’s appointment take effect from Saturday, June 29, 1963, before he made operational Section 180 of the constitution, which would have required the Public Service Commission to do the hiring. As noted above, London never saw the telegram before Kenyatta made the announcement – and that angered authorities there as they had no input.

It appears that given a chance, they would have rejected Njonjo’s appointment. The British were concerned that with Njonjo in charge of the State Law Office, they were going to have "a very difficult time over the amendment of the constitution". It appeared they preferred to have a say in appointing the Attorney-General, but Kenyatta had acted swiftly, presenting his proposal and pushing it through.

Moving forward, the British deliberated on how to handle the situation. "If we are going to stand any chance of getting reasonably wide support for changes which are necessary to us (emphasis mine)...it seems to me very important that, wherever possible, in cases similar to the present case, we should try to restrain Kenyatta from going too far," suggested the under-secretary of state for the colonies.

"I have been nervous that he might take the bit too much between his teeth on defence and external affairs, and I hope that in general, you can get across to him that it is in his interests not to press for arrangements which will be duly provocative to the opposition.

Former Attorney General Charles Njonjo takes oath of office soon after independence.

"I don’t think that the problem was whether Kenyatta was provoking the Kenya African Democratic Union (Kadu). Britain was just feeling slighted. The primary issue was Attorney-General Webb representing Kenya at the East African Federation summit in Kampala. As Governor Malcolm MacDonald put it, "The politicians were clearly unwilling to discuss their plans in front of an expatriate civil servant". For instance, during a meeting in Dar es Salaam and London, Constitutional Affairs Minister Tom Mboya insisted on taking Njonjo with him.

"The general political pressure for Africans had also been growing. Other proposals for advancing Njonjo had been laid and were awaiting Mboya’s return from London, but the matter came to a head at last Thursday’s Cabinet meeting when the whole question of the expatriate civil service was discussed," MacDonald said.

After that meeting, Kenyatta followed the governor and suggested Njonjo’s appointment.

As Macdonald informed the secretary of state, Kenyatta sought to have Webb replaced "as soon as possible".

Circumventing constitution

The governor then called his deputy Griffith-Jones and Webb, and as he mentioned, "We agreed that it would, in all circumstances, be impossible to refuse the request since this could only make my relations with Kenya ministers very difficult, and embarrass Webb personally and officially particularly since Njonjo was being used outside his proper sphere under Mboya’s direction and without reference to Webb".

It appears that after the June Madaraka government was installed, Mboya was bypassing the Attorney-General and consulting Njonjo instead. London believed the governor should have waited for the Public Service Commission to name the Attorney-General. "It did not seem to matter significantly whether Njonjo was appointed to be or to act as Attorney-General," they said but emphasised that it would have been "infinitely preferable" for the appointment to be made by the commission. They did not make a secret that they were unhappy. The tone of their "secret and personal" note written to MacDonald by Sir Hilton Poynton, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, dated July 1963, was telling.

"I feel bound to make it clear to you that we consider that we were treated cavalierly over this matter. The secretary of state is answerable to Parliament for the manner in which you act in your discretion, and we must ask that in future, where important issues such as this are involved, we should be given an adequate opportunity to tender our advice to the secretary of state before you are irrevocably committed," Poynton wrote. Britain was eager not to be seen as opposing the appointment of an African as Attorney-General, but the concern of the officials there over the process was evident.

"What particularly worried us was not so much the replacement of Webb by an African as the manner in which you appointed him. We still think that it would have been infinitely preferable for the substantive appointment to have been made by the Public Service Commission," Sir Hilton Poynton said. Njonjo’s appointment was irregular as Section 180 of the Constitution was not yet operational.

Actually, the governor was questioned about the rush. "Is it really necessary to appoint Njonjo on June 29 merely for the purpose of attending the Kampala conference? His advice would be equally available even though he were not appointed Attorney-General." Another concern was how the opposition, Kadu, would react. "If you proceed as you propose, is there not a risk that opposition groups will allege that you have connived with the Prime Minister to circumvent the agreed provisions of the constitution, in order to put in the Prime Minister’s nominee in this sensitive post? Will it not further inflame Kadu’s suspicions of (ruling) Kanu’s intention regarding the constitution?" asked Kitchart Poynne.

But the questions arrived too late in the evening. Kenyatta had already made the announcement, and even as London suggested that Webb be appointed as an adviser to the governor and that Njonjo be appointed on an acting basis "pending bringing into operation Section 180, with the substantive appointment to be made on the advice of the Public Service Commission" Njonjo was already planning to take over. That was the drama behind Njonjo’s appointment as the first African Attorney-General.