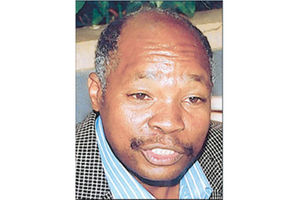

Some of the shareholders of Embakasi Ranch demonstrate outside the Supreme Court on 24 May 24, 2022. (Inset) Former Embakasi MP David Mwenje (left) and Muhuri Muchiri.

When David Mwenje reigned, he started a campaign in Nairobi’s Eastlands to settle the “landless” on “idle land.”

In Embakasi, where he became MP in 1988, Mwenje was the ultimate “Baba wa Squatters” and lord of impunity.

Diminutive, pompous and rowdy, Mwenje always suffered the short man syndrome – the Napoleon complex.

Though he walked with a gait of confidence, he had some Napoleonic ruthlessness, was rough and protected himself with a vigilante called Jeshi la Embakasi.

In his campaigns, Mwenje, like all other politicos in Embakasi, promised to “settle” the landless, especially in the sprawling Dandora, Mukuru and Soweto slums.

The problem was that there was no empty land. He targeted private land owned either by the Embakasi Ranching Scheme, led by his nemesis, Muhuri Muchiri, or the expansive Kiambu Dandora farm.

The other target was Gerishon Kirima’s Njiru farm, where he was always repulsed by cleaver-wielding butchers from Kirima’s Njiru slaughterhouse.

During his reign, Mwenje worked with government administrators and City Hall officials to achieve his notoriety.

As a former councillor, he knew the corridors of power and regularised farm invasions with allotment letters.

Some who claimed ownership of plots within the Kiambu Dandora farm produced allotment letters bearing Mwenje’s official letterhead as the MP for Embakasi or as local ruling party Kanu chairman.

In 1990, for instance, some squatters claimed Mwenje and the District Commissioner had “authorised” them to occupy Embakasi LR No. 209/11543 and LR No. 209/11546, a former sisal farm, which they said belonged to the government.

They also wanted to claim adverse possession, on account that they had lived on the land for more than 13 years.

The Court of Appeal, however, held that no one can claim adverse possession against public land.

It was also found that the land was already private property, having been allocated earlier.

Finally, the Mwenje group was ordered out.

In their February 18, 2018 ruling, Justices Martha Koome, Alnashir Visram and Wanjiru Karanja said that while they were “empathic as always with the less fortunate in society, and especially to the 1,500 families who had invaded the land, the respondents also have a constitutional right to own and utilise their property within the confines of the law, without interference”.

1,500 squatter families

The Appellate Court judges then told the 1,500 squatter families to leave the property rather than wait for eviction, which they said was not unlawful.

“There is in place law pertaining to evictions, and evictions do not need to be violent or inhumane. The appellants have the option of vacating the property voluntarily and need not wait to be evicted,” the three judges said.

Populating Embakasi with followers has always been a strategy employed by politicians seeking to control the constituency.

Without squatters and without addressing the land issue, most Embakasi politicians have no other pledge.

It was a strategy used by Mwenje and Muchiri – also a former MP – in their quest for votes. While Muchiri was protective of the Embakasi Ranching land, which he chaired, Mwenje instigated government investigations on Muchiri’s leadership and would use the floor of the House to attack the leadership of the ranching company. Muchiri used the shareholders as pawns.

Mwenje was always worried that Muchiri would use those he had settled as his supporters, and the only way to break that would be to bring in a new set of squatters.

Jeshi la Embakasi would come in handy. At one point, several people died as Mwenje attempted to get new settlers into the Kiambu Dandora farm.

Mwenje’s equal was a man called Mwangi wa Thuita, a lad who was Muchiri’s bodyguard.

Thuita always carried two knives and a sword hidden in his jacket – just in case.

He later became the chairman of Embakasi Ranching after Muchiri’s death.

Nairobi leaders Maina Kamanda, David Mwenje and Dick Wathika address the press at the Boulevard Hotel, Nairobi.

In 1991, Lands Minister Darius Mbela supported Mwenje and described Embakasi Ranching directors as “crooks”.

Mbela told Mwenje: “We also moved to ensure that crooks who have been running Embakasi Ranching Company do not exploit their poor shareholders.”

“We have a team headed by the deputy provincial commissioner and includes a number of people who are its members, and also the Criminal Investigation Department.”

It is now known that this was the group that pioneered the double allocations in Embakasi as more shares were sold and squatters given Embakasi land.

Mwenje had found a way to tame Embakasi Ranching Company directors. After Muchiri’s death, the lawmaker continued to wrestle with another group led by Thuita.

Mwenje and other politicians interested in the Embakasi seat used the squatters as baits.

Potential voters

It is a practice that was also used by councillors who would allocate public land for setting up kiosks and settlements in the hope these were potential voters.

It has never ended, and politicians would always side with squatters in the hope they would form a battalion of supporters.

The Kirima family has found itself in a conundrum where political interests are part of the property row.

Mwenje had a political home in Mowlem, near Dandora, where he led a Spartan life.

It was a wooden house with no opulence. His supporters and brokers would be found in his Leader’s Corner Bar in Umoja I, where he plotted political moves.

Interestingly, Leader’s Corner was built on a grabbed playground set aside for Umoja 1 estate.

Most politicians in Nairobi’s Eastlands maintained such sites of contact with supporters.

They had taken a cue from Muchiri, who used to have 100 acres in Riara, Kiambu, but stayed at his Gaylord Hotel in Nairobi.

After being jailed for stealing coffee, Muchiri opted to stay in his new Athi River bar, “Studio 45”.

Embakasi politics rotated around these figures. When he plunged into politics, Mwenje used the squatters to win the Embakasi seat.

During the 1988 queue-voting election, Mwenje defeated Muchiri by 2,294 votes against 1,397.

In the secret ballot, Mwenje received 4,610 votes against Muchiri’s 3,850. He had stamped his authority and shown the power of squatters.

This script was followed by Ferdinand Waititu, who knew how difficult it was to get support from voters settled by another politician.

The desire to populate Embakasi with potential voters – which included invasions of private properties – drove the local politics. Villages mushroomed, and “self-help” groups emerged with registered members.

It is these groups that were always allocated land.

Former Nairobi Mayor Dick Waweru, previously the Ruai councillor, had a block of squatters he had brought from Githunguri. They had been allocated land in Embakasi.

Some were on the land left aside for the Nairobi sewage extension before they were evicted.

Looking at the ongoing Kirima land saga and the politics of Embakasi, one can see parallels.

After Kirima’s death, or as he started ailing, the land he had always protected from squatters was invaded.

What began as a criminal activity by David Kamau Mwenje became a tradition.

Today, land invasion in Embakasi is so entrenched that the sanctity of the title deed is not respected.

While the Kirima family fight is between them, local politicians and the squatters as pawns, it is also about the fate of landowners whose property can be invaded, the size notwithstanding.

[email protected] @johnkamau1