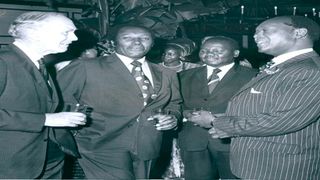

From left: British Foreign Secretary Alec Douglas-Home, Foreign Affairs Minister Njoroge Mungai, House Speaker F. M. G. Mati and Attorney-General Charles Njonjo in Nairobi on February 7, 1974.

|Weekly Review

Premium

Charles Njonjo and Njoroge Mungai: Death, drama and sabotage in Jomo Kenyatta succession

On the day that Charles Njonjo was returning home from London following the “traitor” uproar, Dr Njoroge Mungai was addressing a Kanu rally in Kamukunji calling for the dissolution of the Cabinet. It was tit-for-tat. Here is the inside story on Jomo Kenyatta’s succession – and the drama that came with it.

When Mzee Kenyatta died on the morning of August 22, 1978 – the Western media had cast their eyes on Mungai as a possible successor. Though the Constitution was clear that the Vice President, Daniel arap Moi, would assume power for 90 days pending elections, Mungai was regarded as the most suitable candidate.

Over the years, Mungai had made his calculations right. But in 1974, he was defeated for the Dagoretti Constituency seat by a little-known University of Nairobi don, Prof Johnston Muthiora, who had polled 8,533 votes against Mungai’s 6,399. Major international newspapers picked the story.

Those who wanted Mungai out of the Kenyatta succession had managed to put the first barrier. Mungai might have assumed that his closeness to Mzee Kenyatta and as the President’s physician would guarantee him power. It didn’t. But power had gone into his head, already. He stepped on many toes, first by humiliating Vice President Jaramogi Oginga Odinga in 1965. During the United Nations Day, Mungai’s group ensured that he would read President Kenyatta’s speech, even though Odinga was present. And when Odinga attended the party of a German correspondent, Mungai deported the journalist.

“You couldn’t help but feel sorry for Odinga. Badly advised, sensitive to pin pricks, pressed by his oriental sponsors, shadowed by the police, he was reported to have started drinking heavily and taking bhang,” alleged William Atwood, the former American ambassador, in his banned book, The Reds and the Blacks.

In 1970, a Nation journalist, John Platter, asked Mungai about his days at Fort Hare University in South Africa, where he graduated with a BSc degree in 1950. “It has been said that you are a bit of a playboy. One lady from South Africa told me you were quite a lad. Were you and are you now?”

“My gosh... ,” said Mungai, “I wish you would tell me who she was. No seriously, that is not true; I was not a playboy at all. If you can call being able to smile under difficult conditions as being play-boyish, then that’s your interpretation.”

Mungai lived well. In his house was a stuffed lion flanked by a cheetah. At the Norfolk, where he frequented, you could catch him taking Aquavit and champagne. He married late and was always in the company of white women. Fort Hare shaped Mungai’s politics. It was the bastion of black politics. His room-mate was Mangosuthu Buthelezi, who later became the Zulu leader and prominent South African politician, while Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe was a schoolmate.

Mungai was part of Kenyatta’s inner circle, which included Mbiyu Koinange, Charles Njonjo, Bruce Mackenzie, and James Gichuru. Tom Mboya had been recruited into the circle to drive Odinga out of power. But his ability to organise and rally for a cause frightened the inner circle. Once the conservatives had dispensed with Odinga, Mboya’s role within the inner circle was over. “The unity of purpose forged by the conservatives in order to drive Odinga and the radicals from power quickly evaporated once this task was accomplished,” observes Wunyabari Maloba, the University of Delaware history professor, in his book, The Anatomy of Neo-colonialism in Kenya.

Kenyatta did not only trust Mungai with his health – but also his political survival. By holding the twin docket of Defence and Internal Security, Mungai was the most influential personality in Kenya. For instance, in June 1969, he was sent (together with Agriculture Minister Bruce Mackenzie) to British Prime Minister Harold Wilson to “discuss Kenya’s need for jet aircraft”. That Njonjo was not part of this team would later be clear: Njonjo and Mungai belonged to different political camps and Mungai must have sweet-talked Kenyatta to leave him out.

To tame Mungai’s rise and hubris, the Njonjo group sponsored a candidate to face him during the 1974 General Election. It was the only way to stop him. As Kenyatta’s physician, only Dr Mungai had the details about the President’s health. A second physician, Dr Eric Mngola, the Director of Medical Services and later the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Health, was brought into the circle. Also, at one point, Njonjo brought South Africa’s Dr Christiaan Barnard to treat Kenyatta as part of the succession intrigues.

It would not be surprising that the Njonjo group’s physician, Dr Mngola, and Coast Provincial Commissioner, Eliud Mahihu, would be at State House, Mombasa, on the night Kenyatta died. Interestingly, Mungai and his group were not in sight.

Some say that Koinange — who never left Kenyatta’s side — had been hoodwinked to leave Mombasa that evening to meet an investor passing through Nairobi. It was a big mistake.

The biggest obstacle

Before politics got the better of him, Mungai had graduated as a doctor from Stanford University and did his residency at the prestigious Presbyterian Medical Centre in New York. “I learned medicine at Stanford. I learned politics at Stanford. And I learned mixing with all kinds of people — communicating with people from various parts of the world,” he once said.

After graduation, he was featured in Time magazine. At 37, in 1963, Mungai was named Kenya’s Minister for Health and Housing. He was rising steadily. As Kenya’s Foreign Minister, Mungai became the most notable African personality of his time. As Minister for Defence and Internal Security, everyone thought Mungai had built solid networks. Thus, when he lost his election in 1974, he knew that this was more than a Dagoretti race. He claimed that “some people” campaigned against him. It was perhaps bigger than that. Mungai had annoyed the British for openly spearheading the Africa campaign against arms sales to South Africa.

Pretoria and London had tried convincing some African leaders that the arms were supposed to keep the sea routes safe. But Mungai had remained the biggest obstacle. Cyprian Fernandes, one of the journalists close to Mungai, recalled a 1970 incident where the British managed to silence Mungai through trickery when he was attending the Commonwealth Summit with VP Daniel arap Moi.

“After the conference opened, there was a short debate on the (arms) subject. The clever British Foreign Secretary, Sir Alec Douglas-Home, nuked the arms campaign… he told the summit that the heads of government or leaders of the delegation should decide the arms issue.” Douglas Home knew that Mungai was the chief architect of the campaign. “On the eve of the Big Chiefs’ meeting,” writes Fernandes in his book, Yesterday in Paradise, “the senior members of the Kenya delegation decided that the campaign could not succeed with Mungai in attendance”.

They plotted to have Moi absent himself by feigning illness and thus give Mungai a chance to present his case as the head of Kenyan delegation.

Recalled Fernandes: “With that, the whole bunch of Mungai’s support crew, analysts, speechwriters and researchers headed for the makeshift office to update the presentation for the meeting. Later that night, I went to dinner with Moi and Njonjo. Everyone seemed to be in a joyful mood. Moi could not stop laughing as Njonjo and I got stuck into our escargot. ‘You guys are eating insects’, he said…. when we returned to our hotel, I popped into Mungai’s room and played the devil’s advocate on some parts of his presentation. Before I left, he said: ‘This is what we have been working for the past two years, and the moment has arrived’.”

If Mungai had succeeded at that international level, he would eclipse everyone. During the poolside meeting, Njonjo had remarked: “I don’t know why you people are bothering with all this. If it was up to me I would open diplomatic relations with South Africa tomorrow.” Fernandes writes: “The next morning most of the team was up by 7am for breakfast, except Mungai. I later found that Moi had called Mungai very late in the night and had told hm that he, not Mungai, would be going to the Big Chief’s meeting.”

In another article he wrote in 1982, he said that “Douglas-Home… knew full that most African heads of delegations would be silent without their foreign ministers.” While Moi knew that Njonjo was fighting Mungai, he never knew that Njonjo was planning to fight him later. Mungai’s defeat by Muthiora was part of Njonjo’s fight to tame his rise. It was big news. On Muthiora’s side was Njonjo and Moi and they effectively mobilised for their candidate. Njonjo had told Mungai in Kikuyu during the campaigns: “Uguthie guthandura Mbembe” – meaning you will go shell dry maize. It was a loaded statement.

But the saga deepened. After his October 1974 victory, Muthiora left the country for India for a 17-day tour from March 28, 1975. But he returned two days ahead of schedule after he felt unwell. He complained of pain in the chest. He was taken to the hospital and treated by a Dr K.E. Thomas. A heart specialist also found that his liver was enlarged. After some injections and tablets, Muthiora felt better, went shopping, and decided to fly back. But two days after arriving in Nairobi, he was admitted to the hospital. He died a week later. Muthiora’s death would later be used against Mungai in his campaigns – and he always lamented about some caricatures depicting him as a killer. But Muthiora’s death remained a mystery.

By the time Kenyatta died in 1978, Mungai was a nominated MP – silenced by the politicos. He hardly spoke in Parliament. Those who knew the pre-1974 politician thought he had some more muscles left by 1978. He hadn’t. It was the group of Njonjo and Moi that was now calling the shots.

In 1979, Mungai was elected again as Dagoretti MP and it was now Njonjo’s turn to go and “shell the dry maize”. When the ‘traitor” saga started, Mungai called a rally in Kamukunji and started the campaign against Njonjo. It was tit-for-tat. Both had missed the presidency – and both sabotaged each other.

[email protected] Twitter: @johnkamau1