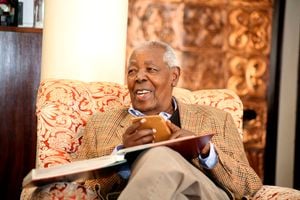

Former President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

Minister Bruce McKenzie secretly held a meeting with the British Secretary of State to help draw a plan to secure Kenya’s stability and preserve the President’s dignity in sickness or death after Mzee fell seriously ill in Mombasa.

Previously restricted documents marked “top secret” reveal how plans and procedures, which could be followed if Kenya’s first president Jomo Kenyatta fell ill or died, were hurriedly and meticulously drafted after he became seriously sick in Mombasa on May 4, 1968.

The situation was so poorly managed that Bruce McKenzie, perhaps the most forward-thinking minister at that time, secretly held a meeting with the British Secretary of State to help draw a plan and avoid such chaos in future to preserve the president’s dignity in sickness or death.

An undated photo of the President Jomo Kenyatta receiving a cheque for Sh22,500 from Commerce and Industry Minister Mwai Kibaki at State House, Nairobi. Looking on is Maina Wanjigi, Executive Director of the ICDC.

Read: Mboya-Jaramogi war: In 1968 Tom complained of failed attempts to reconcile with opposition supremo

This was also considered crucial to maintain the country’s stability. Mzee Kenyatta was at his Bamburi home when he went into a coma that almost plunged the country into a constitutional crisis and triggered a secret power struggle.

As rumours about the President’s well-being swirled around Kenya, then-Deputy British High Commissioner to Kenya B Greatbatch quickly telegrammed the Commonwealth Office on May 6.

“There is evidence that Kenyatta is ill in Mombasa, but we do not (repeat not) yet know how seriously,” he said in the telegram.

The following day on May 7, Greatbatch approached Attorney-General Charles Njonjo who had just returned from Mombasa, to ascertain the truth on the President’s health. Njonjo dismissed the information as rumours, insisting that the President was “as strong as a horse”.

He went on to give a misleading account of how the previous day he and vice-president Daniel Toroitich arap Moi had held a meeting with the President who had also phoned him twice that morning with instructions.

When Greatbatch suggested that if indeed the President was fine then a statement should be released by the government to kill the rumours, Njonjo replied that such a move “might only make matters worse”.

President Jomo Kenyatta, Tanzania President Julius Nyerere and Tom Mboya engage in a light banter at the Nairobi Airport on March 30, 1968. Tom Mboya was assassinated on July 5, 1969.

Instead, he said the President would appear on TV that night. Njonjo’s claims were far from the truth and Kenyatta never appeared on TV.

A couple of hours after Njonjo’s denial, Kenyatta’s nephew and personal physician Njoroge Mungai, finally came out to admit that the President had been sick.

He, however, downplayed the level of the illness by stating that he had been slightly indisposed with a fever but had responded well to treatment and needed a few days to rest.

Though Kenyatta eventually recovered and continued to carry out his duties as President, the situation brought to the attention of his handlers and government officials how unprepared they were.

Politically, Kenyatta was partly to blame for failing to choose a successor, exposing the country to a constitutional crisis and power intrigues in case of his sickness or death.

On the same token, senior government officials and his handlers should have known better that at his advanced age, Kenyatta was bound to suffer from age-related ailments, and therefore emergency measures needed to be put in place in case of anything.

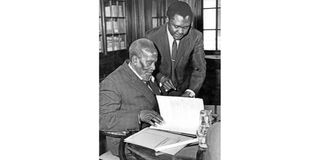

President Jomo Kenyatta (left) with Kanu secretary-general Tom Mboya after a three-hour National Executive Committee meeting at State House, Nairobi. The meeting was also attended by all provincial Kanu vice-presidents and vice-president Daniel arap Moi.

He had suffered a minor thrombosis in the leg just two years earlier in mid-1966. Although the blood clot was dispersed, Kenyatta continued to suffer from recurrent phlebitis.

He was also known to have angina. Despite the scary 1968 incident, which saw the President become comatose for days, senior government officials still slacked off in their slumber, waiting to be caught flat-footed yet again.

Perhaps they were influenced by the prevalent misguided belief that Kenyatta was an immortal larger-than-life figure.

It was Agriculture Minister Bruce McKenzie, who after witnessing what had transpired in Bamburi, decided to initiate emergency measures to deal with similar situations in future.

On June 1, 1968, almost a month after Kenyatta became seriously sick, McKenzie held a secret meeting with British Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs George Thomson, who was on an official trip to Kenya.

The two discussed matters related to Kenyatta’s health, how everyone had been caught flat-footed and whether the British government could assist him draft a contingency plan.

The meeting was at the residence of Greatbatch and was also attended by High Commissioner Eric Norris. McKenzie said Kenyatta had recovered fully but the doctors had advised him to avoid as much as possible looking at routine papers and taking decisions on such papers “because such type of work could disturb him”.

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and Tom Mboya share a joke at the 1962 independence conference in London.

However, the doctors thought Kenyatta could still go on tours and meet people because it was healthy to keep fit.

Narrating what transpired as Kenyatta lay in a coma, McKenzie revealed that though the President fell sick at lunchtime on Saturday, May 4, 1968, Moi and Police Commissioner Bernard Hinga only came to know about it the following day in the afternoon.

Njonjo also learnt about it on the same day as Moi but in the evening while the head of the Special Branch (Directorate of Security Intelligence) James Kanyotu was informed two days later on May 6, in the morning.

According to Mckenzie, this poor communication and coordination – whether done intentionally for political reasons or out of negligence – revealed the lack of planning in case of the president’s serious illness or death and underlined the need to draw up an immediate contingency programme.

He went on to suggest to those present at the meeting, including the British Secretary of State, that it was important to decide in advance what was to be done in all important matters from the form of state funeral to the necessary political and security decisions.

Because of the sensitivity of the matter, Mckenzie felt that the plan should only be known by a small circle within the government made up of himself, Njonjo and Moi.

In making his case, the minister who was once accused of being a Mossad agent, argued that Jomo Kenyatta was an important figure and “any preparation for his sickness or death should be first class”.

McKenzie pointed out that if the plan was carried out efficiently and with dignity, it would contribute to Kenya’s prestige abroad and political stability at home.

Before flying back to London, the British Secretary of State gave full support to the proposal and tasked the two British diplomats present at the meeting to assist McKenzie in drawing up the plan.

Greatbatch consequently shared details of the meeting with Michael Scott of the East African Department in London, stating: “Bruce McKenzie had asked the Secretary of State for Commonwealth in a private meeting on June 1 whether this High Commission could very discreetly assist him in producing plans and forms of procedures, which could be followed if President Kenyatta fell ill again or died.”

Scott replied by expressing his full support.

Greatbatch showed his appreciation by stating: “I have since been glad to see from your letter that you are basically in agreement with us about what is required.”

With the Commonwealth Office in London fully behind the proposal, Mckenzie and the deputy British High Commissioner began holding meetings to draw draft contingency plans.

Also present during these meetings were three senior diplomats at the British High Commission namely Stanley Arthur, Frank Steele and John Ling. To deal with the security and ceremonial aspect of planning, they roped in Kenya’s Chief of Defence Staff Maj-Gen Bernard Penfold and Lt-Col John Slim, an officer from the elite British Special Air Rescue (SAS) and an instructor at the British Joint Services Staff College who was in Kenya to set up SAS training for the General Service Unit.

British Secretary of State for the Colonies, James Griffiths (left), talks to Jomo Kenyatta and a Kikuyu elder in Kiambu in May 1951. Griffiths had come to Kenya to obtain the views of community leaders on constitutional changes.

After three lengthy private meetings, they came up with a draft plan, which McKenzie shared with Moi while British diplomats sent a copy to the Commonwealth Office in London for perusal and consideration.

Motorised medical unit

The draft was titled ‘Contingency Plan for Arrangements in the Event of the President’s Serious Illness or Death’ and marked “top secret”.

It dealt with political, security, ceremonial and medical subjects, among many others. On Kenyatta’s health, the document stated: “Any head of state of Kenyatta’s importance and age should have in addition to his personal physician a team of about six eminent doctors, one of whom by turns is always on call.”

Some of the specialists were to be contracted from the United Kingdom. VHF radio was to be installed in presidential residences and vehicles and connected to the police operations room in Nairobi for quick communication with the medical team.

To ensure Kenyatta received immediate medical care, a light aircraft to help transport a doctor was to be made available at short notice whenever the President was away from Nairobi.

A motorised medical unit was to be formed to be with Kenyatta wherever he went. The motorised medical unit was to be staffed by doctors and nurses.

On the transfer of power, the document stated that if the President fell seriously ill and was incapacitated but did not die, the vice-president was to take over on the authority of the Chief Justice advised by a panel of doctors for up to three months.

In case the President died, steps—including ceremonial procedures described in the Constitution—were to be followed to ensure the vice-president was installed as President as quickly as possible.

For security reasons, a list of potentially hostile Kenyans was to be prepared. These citizens were to be detained when the President became sick or died, and were only to be released after a peaceful transfer of power was established beyond doubt.

Telephone lines to Kisumu, where opposition to Kenyatta was strong, were to be monitored or cut. To ensure everything was carried out as per the programme, it was suggested “that there should be a policy committee made of key ministers under the chairmanship of the vice-president.

“The vice-president should ensure there is always one minister of the committee available at short notice in Nairobi to take command of the situation if the President is indisposed,” the draft said.

“If the President dies either in or outside Nairobi, this minister should remain at the security headquarters until the vice-president arrives.”

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta takes the oath during his swearing-in as Kenya’s first Prime Minister on June 1, 1963 in Nairobi. His party, Kanu, won 83 seats out of 124 in elections in May 1963. On the right is Governor Malcolm Macdonald.

The draft went on: “It is vital that the vice-president should return immediately to Nairobi from wherever the president may have died to take command of the situation.”

According to the draft, the vice president was immediately to chair a special policy committee of ministers in a room separate and close to the operation room at the security headquarters.

To ensure the vice-president kept in touch with police operations when he was outside Nairobi, Moi was to be accompanied by a police wireless vehicle that would maintain contact.

To implement the plan, the paper stated: “We will need no-accountable secret funds. We should, therefore, arrange to have such funds made immediately in the sum of say on which we can call without having to go through the normal process of getting the approval of departments for every item of expenditure.”

The plan addressed many other subjects. Even though Kenyatta outlived it for 10 years, most of its aspects were implemented when he died in August 1978, but others such as the medical aspect failed.

The irony is, McKenzie —who was its architect—died before Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

The writer is a London-based Kenyan researcher and journalist