A cockerel which perched on a casket bearing the remains of the late Bishop Alexander Kipsang Muge.

“Do not step in Busia or you will not go back alive,” Labour minister Peter Okondo warned Church of the Province of Kenya (CPK) – now Anglican Church of Kenya (ACK) – Eldoret Diocese Bishop Alexander Muge in August 1990.

The country was on the edge, with democracy and constitutional reforms crusaders bearing the brunt of a crackdown by President Daniel arap Moi.

Bishop Muge was among the religious leaders who had joined forces with firebrand politicians, lawyers and civil society to force the government to open doors for pluralism.

Politicians allied to the government never wanted critics of the system in their backyards.

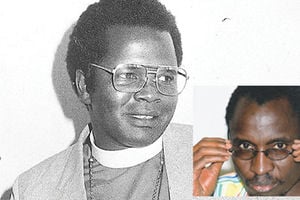

The late Anglican Bishop Alexander Kipsang arap Muge.

Bishop Muge declared he would go to Busia no matter what. He was dead hours after the threat.

The cleric died in a suspicious road accident near Kipkaren River on the Webuye-Eldoret road on Tuesday August 14, 1990.

His death was seen by many as state-sponsored.

Muge, who had trained as a police officer, was consecrated aged just 35. The bishop, who died seven years later, was outspoken and a champion of good governance, accountability and human rights.

He was installed as bishop on June 5, 1983, some 10 months after the August 1, 1982 attempted coup. The Kanu regime was cracking down on perceived dissidents.

Retired Bishop Peter Njenga says after August 1982, there was systematic alienation of members of a community President Moi believed had organised the attempted coup.

Vocal and inquisitive

Muge had served as Bishop Njenga’s assistant during his tenure as provost of All Saints Cathedral, Nairobi. Muge began his tenure by defending the community being isolated by the government.

“He challenged the system, becoming vocal and inquisitive. I’m sure the system must have worked on a plan to finish him,” the retired cleric says.

Dr Christopher Ruto, current bishop of ACK Eldoret Diocese, says it was difficult for Muge to operate because he served in Moi’s home region.

People were not allowed to say things contrary to what the establishment wanted to hear and Muge could not stand that.

The late Bishop Alexander Kipsang Muge, his wife the late Herma Muge and their children Andrew Muge (standing second left), Armon Muge (standing second right), Esther Jebet Muge (seated left) and Elizabeth Muge.

In one of the visits to Kabarak – Moi’s home – he was told the government was ready to support his projects.

“He said: ‘I agree only to work with whatever is true, just and noble for the people,’” recalls Bishop Ruto.

The 80s and early 90s were turbulent times, with crackdowns on Mwakenya movement, arrests, torture, disappearances and detentions without trial.

The more the government visited terror on people, the more the activists pressed. The climax was the first Saba Saba rally and protests on July 7, 1990.

Religious leaders were singled out as the biggest threat to the government. Unlike politicians who could be denied permits to hold meetings, the clergy had a free pass to pass their message during mass.

The constitution also demanded a permit for a meeting of more than five people.

Muge was clearly a marked man living on borrowed time.

Retired Presbyterian Church of East Africa minister, Timothy Njoya, says he used to join Muge at Sirikwa Hotel, Eldoret, to pray and plan their sermons nearly every Monday.

“Practitioners of dictatorship and oppression were threatened to hear they had no legitimacy,” recounts Njoya who was defrocked for two years.

“We had taken the Church to the streets. The media became the extension to our sermons. Other people like Sheikh Balala, Salim Bahmariz and Sheikh Juma Ngao supported the movement. The country was reverberating,” he says.

Bishop Muge was travelling to Busia to resolve a row between Katakwa and Nambale Deaconries.

Nambale was mainly inhabited by the Luhya while Katakwa was predominantly Teso. The latter were threatening to break away as they felt a qualified person from the region was not picked as the new bishop. CPK installed Isaac Namango as Nambale bishop, instead.

Former Labour minister Peter Okondo who warned Bishop Muge against stepping in Busia.

CPK bishops were also divided, with some opposed to the creation of the Nambale Diocese.

Another crisis had unfolded earlier. The charred remains of Foreign Affairs Minister Robert Ouko were found in Got Alila, a few kilometres from his Koru home, on February 13, 1990.

There was a belief in government circles that Muge was among the people who had information on the killing.

Muge defied the threat made by Okondo and went to Busia on August 14, 1990. While in Busia, he promised to name those who had killed Ouko as soon as he returned to Eldoret.

In the car from Busia on the way to Eldoret were Muge, his driver Davies Omanyo and the bishop’s secretaries, Claire Kerubo and Rhodah Cheboo.

From the border town, the group used a different route – Busia-Kisumu – and not the one they had used earlier, Bungoma-Malaba-Busia.

The vehicle was stopped at a road block in Luanda, with one of the officers speaking to the bishop in Kalenjin.

The bishop changed his route again. Instead of using the Kapsabet road, he went up to Kakamega where he hosted those in his convoy of about six vehicles to a late lunch at Golf Hotel.

This poignantly turned out to be his last supper. As the clock ticked towards 3.30pm, the bishop took over as the driver but would be dead minutes later.

A school milk truck rammed Bishop Muge’s car near Kipkaren River on the Webuye-Eldoret road, killing him on the spot.

Bishop (rtd) Njenga says he attempted in vain to contact his friend.

“I tried to call him from that Friday to Tuesday when he died. I wanted to warn him of a trap they had set for him and that he should not go. I would have given him the message but never had the chance to do so,” he says.

“I had heard from anonymous callers. Two unidentified sources asked me to warn him.”

Esther, Andrew, Amon and Elizabeth were teenagers when their father died. Their mother, Herma, died in 2018.

Esther recalls that on the night of August 13 before his trip to Busia the following morning, her father, who she says was jovial, called her to his bedroom where they had a warm conversation.

“He was asking me things like: ‘Would you like to go to the United States? You know I am friends with the ambassador. It will be done’. Then he was like: ‘Have I ever wronged you? You are my firstborn daughter and I will do anything for you’,” Esther recalls.

Candid conversation

Her father had already left for Busia when she woke up the following morning. Esther then went to see a friend in Kisumu, a visit cut short by her father’s death.

Amon says there were always threats against his father.

“You issued a threat today and he was there tomorrow. We were used to these things,” he says.

Esther says the tragedy pierced her heart as she had had a candid conversation with her father on the eve of his death.

Alexander Kipsang Muge.

“It feels like yesterday. The plans he had for us are still fresh in my mind,” she says.

The Muge children were home for the August holidays when he died. The bitter reality of the tragedy hit hard when schools opened for third term the following month.

“We used to give our father the shopping list but it was mother we began operating with. That is when we knew the magnitude of the tragedy. Elizabeth, our younger sister, did not want to return to school. I was the only day scholar,” Amon says.

The Muge family and CPK settled for August 22 as the burial date.

However, the government wanted another date since the day coincided with the commemoration of President Jomo Kenyatta’s death.

The Muge household and the church stood their ground. It meant Moi had to make arrangements to condole the family before the funeral.

Some Cabinet ministers who attempted to visit the Muge family home had been turned away by angry crowds. President Moi went alone almost quietly.

Bishop Christopher Ruto, Head of the Anglican Church of Kenya Diocese of Eldoret, accompanied by Rev. Rosemary Pino, Priest at St Matthew's Anglican Church of Kenya Cathedral in Eldoret town, Uasin Gishu County, at the late Bishop Alexander Kipsang Muge mausoleum on August 7, 2024.

While at the homestead leading prayers, a cockerel emerged and jumped on the president, to the surprise of many.

“My uncle took the bird and attempted to throw it away. As soon as it landed on the ground, it again made for the president making a lot of noise. Moi continued praying. We cannot explain the event,” Amon says.

Esther says the cockerel noisily jumped on the table, scattering the cloths.

“People were surprised. Their eyes were fixed on the cockerel even during prayer. Moi prayed alone,” Esther adds.

When Muge’s body was taken to his home for overnight stay before being moved for burial at ACK St Mathew’s Cathedral in Eldoret, there was a similar occurrence.

As the casket was opened to allow viewing of the body, a cockerel jumped on it. Nobody attempted to remove it from the coffin.

“We still have the pictures,” Amon says, adding that there were no photos of the development when Moi was around.

A past photograph on August 07, 2024, of a cockerel which perched on a casket bearing the remains of the late Bishop Alexander Kipsang Muge who was the Head of Anglican Church of Kenya Eldoret Diocese, who died in a controversial road accident in 1990 at Kipkaren River in Uasin Gishu County, when the body was taken to his home in Elgon View Estate in Eldoret town of Uasin Gishu County.

The bird was never slaughtered and was left to die naturally.

Muge, who was 42 at the time of his death, would have retired in 2011. He had served as bishop for seven years.

“Mother is buried at home and father is at the church. We would wanted to have them buried next to each other. The church definitely discussed with mother and agreed that was the way to go,” she says.