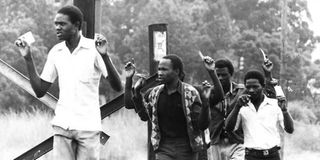

City residents flash their IDs in Nairobi after loyal soldiers regained control.

On the 42nd anniversary of the abortive 1982 coup, we traced four Kenya Army helicopter gunship pilots who had a frontline role in suppressing the rebellion. The quartet, for the first time, speak out about the dramatic events, including the mission to bomb Eastleigh airbase, during one of Kenya’s darkest chapters

“Why are we getting VIP reception?” Captain Charles Wachira asked his colleague Captain Joseph Muiruri through the radio communication as their low-flying Kenya Army helicopters hovered over Embakasi garrison. On the ground below was a bemusing spectacle. Kenya Air Force soldiers had come out to the pavilion of this base that was formerly old Embakasi airport to watch the approaching helicopters. Ordinarily, the air force men had no time for their counterparts from the army. They openly displayed their disdain for them. This contempt raged from the mundane- like air force gatekeepers refusing guests of army men entry- to what is considered mutinous in the disciplined forces- refusing to salute a senior. After all, the air force’s Ground Air Defence Unit (Gadu) personnel were the majority in the camp.

Wachira and Muiruri had graduated as army officer cadets from the Kenya Armed Forces Training College in Lanet in 1976 but had later joined the 50th Air Calvary Battalion (50 ACB), an airborne anti-tank battalion. The new army unit had hurriedly been formed in July 1979 and hosted in this base that borders Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (JKIA). Most members of the new army unit, however, lived in Lang’ata and Kahawa barracks because there wasn’t enough accommodation at Embakasi. Tension between officers from the two services had risen to boiling point. The soldiers who initially shared an officers’ Mess even had separate facilities established due to the bad blood. Nevertheless, the army men had become accustomed to being ignored by their Air Force peers.

Retired Col Hussein Farah, Major (Rtd) Munyeki Wachira, Major Retired Hussein Mohammed and Colonel Joseph Kibira Wachira.

But on the evening of Friday,July 31, 1982, it was curious that their rivals had taken notice of their arrival. A squadron commander, Wachira smoothly landed the helicopter as did his friends. 50 ACB commander Lt Colonel Chris Kitundu offered to entertain the exhausted pilots at the nearby JKIA club. They craved for their favourite cold Tusker beer. For days, army battalions were holed up in the harsh terrains of north western Kenya for drills. Somalia had threatened to invade and annex a part of Kenya. It wasn’t considered an idle threat. Especially coming after the Ogaden War (1977–1978) following Somalia’s invasion of Ethiopia. That threat had informed the army exercises in Kapenguria, Kacheliba and Lodwar to simulate an invasion.

Kisumu had been designated the ‘enemy state’ that saw jets fly past in supersonic boom in a mock attack. As the jovial army soldiers drove back to the camp from JKIA club at midnight, an even more surprising welcome awaited them. “The air force soldiers opened the gate and, for the first time, saluted us,” Wachira- who retired from the army as a major in 1988 and flew civilian aircraft until 2020- recollected in an interview with Nation.Africa last month. Were they missing something? It wouldn’t be long before the mischief would become evident. A tragedy that would cost hundreds of lives and forever alter the country’s history.

Commotion

At around 1am, there was commotion in the camp. Gunshots shattered the calm night. Muiruri, who was the camp’s adjutant (a military officer who acts as an administrative assistant to a senior officer and in charge of discipline) woke up, dressed in a track suit and smoker’s jacket. He went out to check what was happening. At the gate, he found a soldier lying on the ground. He had been shot dead. He asked the guards what was happening but the rude response caught him by surprise. “Don’t ask such questions, can you sit on the tarmac,” the guards snarled back. By then he noticed a group of soldiers and civilians sitting on the tarmac with armed soldiers around them. “Afande, watakuua (boss, they will kill you). Just come sit here,” one of the officers sitting on the tarmac pleaded with Muiruri. Apparently, hostile air force soldiers had rounded up his colleagues and civilians who had been enjoying drinks at the officers’ Mess and held them hostage. “For about 15 minutes, the air force soldiers were chanting ‘power! power!” Muiruri recalls as bursts of gunfire lit up the night. The soldiers then scrambled into trucks shouting they were heading to Eastleigh airbase.

Security forces patrol the streets of Nairobi after the coup attempt.

The hostages were left sitting on the tarmac. Muiruri recognised one of the armed men was the bar man- an army Private- now donning a Major’s uniform. Then all fell silent. Muiruri rushed to Wachira’s room to narrate the harrowing ordeal. Unknown to the army officers, some junior air force soldiers had planned a coup apparently timed to coincide with the military drill that had held up most army battalions in the remote part of the country. Days earlier at House number K27 in Nairobi’s Umoja estate, Senior private Hezekiah Ochuka, the coup leader, had hosted fellow air force mutineers to plot the putsch. But the surprise arrival of the 50 ACB contingent had seemingly caught the rebel air force men by surprise. By about 3am, Sunday, August 1, the coup was underway. Eastleigh airbase had fallen.

Former President Jomo Kenyatta(left),Brigadier Njoka(centre) and Major retired Hussein Mohammed at Lanet Baracks on March 31,1978 during passout parade.

By 6am, the unmistakable voice of veteran broadcaster Mambo Mbotela announced the coup to the nation. Rebel forces had abducted him from his house to make the broadcast at Voice of Kenya (VoK). The rebels, who styled themselves ''The Aug. 1 Revolution,'' had declared that a ''National Redemption Council'' had toppled President Moi’s government and seized control. Senior private Hezekiah Ochuka, the coup leader, had assumed the title of chairman of the Council. The rebels had announced the country's airports and borders had been closed and ordered the release of all political detainees. The mutineers had accused the Government of imposing a dictatorial one-party state, gagging the press, human rights violations by arbitrarily arrests and a campaign of ''ruthless repression reminiscent of the colonial days.'' The rebels had also railed at a corrupt elite perpetuating rampant corruption and nepotism that had made life intolerable. ''The economy is in a shambles due to corruption and mismanagement,'' the broadcast had said.

A Kenya Air Force rebel on top of a car addresses a crowd at Kariobangi Petrol Station on August 1, 1982.

Back at Embakasi, by 7am, Muiruri and Wachira went to the adjutant’s office. The telephone lines had been cutoff. They could not communicate with Army headquarters. Kitundu arrived from Lang’ata barracks. He had been ordered to takeover Embakasi garrison and disarm the soldiers. That was almost mission impossible as they were roughly 20 soldiers from 50 ACB against nearly 200 armed air force personnel still there. “How many pilots are we?” Wachira remembers Kitundu asking them. They were four- Kitundu, Wachira, Muiruri and Omar. The other pilots were at Kahawa barracks. The pair flew the two helicopter gunships to Kasarani army depot where they were armed with rockets and 7.6mm caliber machine guns.

Kahawa barracks

Two more pilots from Kahawa barracks joined them. The choppers armed with missiles flew back to Embakasi garrison. “We huddled in Kitundu’s office to figure out how to execute the takeover. I went for surveillance at the Gadu officers' Mess where I found small groups of armed soldiers who were not aware of what was going on. And they had no command,” Muiruri recalls. When he reported this to Kitundu, he was instructed to go summon the most senior captain. Kitundu addressed him sternly: “I have an order to take over the camp and kill if I have to. Ask your colleagues to put down their weapons and surrender.” Two things worked out in Kitundu’s favour: the air force soldiers left behind had nothing to do with the coup and trusted him because he had been one of them. Kitundu had been moved from air force to army when the new aviation unit was set up in 1979. “We were so relieved when they complied,” says Muiruri adding, “it would have been a suicidal mission had they resisted as they would have overpowered us.” “That is how we seized control of Embakasi garrison without firing a single shot,” says Muiruri who retired from the army in 1998 after 20 years of service. (After the coup, he discloses, then Chief of General Staff Jackon Mulinge visited the garrison given the astonishing account of its takeover without a gunfight.) Muiruri, however, adds the victory was short-lived. With only 20 soldiers securing the perimeter, they soon realised they were sitting ducks. Officers from the nearby General Service Unit (GSU) attacked Embakasi garrison. Luckily, the helicopter gunships helped repulse the attack. But because they feared the GSU had retreated for reinforcement, the two helicopters flew to Lang’ata barracks to call in support.

Meanwhile, as the day wore on, Army Commander Lt Gen John Sawe was scrambling a counteroffensive by his troops. His deputy, Major General Mahmoud Mohammed, was the operation commander, as loyal forces fought their way into the state broadcaster. The arrival of the helicopter gunships at Lang’ata barracks was greeted with relief. Apparently, Sawe had contacted Ochuka and ordered him to surrender. He had refused. The army commander had decided to bomb the operations centre at Eastleigh airbase. In all, 10 attack helicopters were now at Lang’ata barracks. But two choppers were assigned the Eastleigh mission and Wachira was designated the team leader. Wachira recounts the call that would mark a defining moment in suppressing the coup. A voice boomed on the line: “Wachira, you have been ordered to bomb Eastleigh airbase operations!” But he demanded to know who had given the order. He was informed it was the army commander. He asked to speak to him.

Civilians caught up in the attempted coup of August 1, 1982 walk on the streets while displaying their ID cards.

Then the army boss came on the line. “Wachira, do you recognise my voice?” Sawe posed. “Yes, sir,” Wachira responded swiftly. “You know Eastleigh operations? I order you to destroy it!” Sawe explained he had relayed information for everyone to get out to safety. Anyone still holed up there was considered an enemy. The two army helicopters took off for the deadly mission mid-morning. In one was Wachira and Captain Olang Dulo and in the other was Muiruri and Captain Unshur Mohamed. The one Muiruri and Unshur flew was designated the “high bird” -military parlance for the aircraft thatprovides air cover against hostile fire for the one going in for the kill.Within minutes, the helicopters flying lowly to avoid detection had the target in sight. “Going hot,” Unshur, who retired in 1988 after 12 years in the military, recalls Wachira informing them. Wachira pulled the trigger. A burst of machine gun fire. Rockets launched. A huge blast. The first missed the target. But four others, in quick succession, obliterated the target. Muiruri fired but the chain machine gun jammed. He flew round and approached the tower. Then fired again. Soldiers on the ground were fleeing. Mission accomplished, as they flew back they spotted a buffalo military transport aircraft taxing on the runaway at Eastleigh airbase. They had radioed their seniors to find out whether it was friendly or enemy aircraft. “I was told to stand by. I was circling in the air,” Wachira narrates. “The buffalo took off flying towards Athi River. By the time I was being ordered to shoot it down, it was too late,” Wachira reveals. “We gave chase but the aircraft was moving too fast for our helicopters. We were doing roughly 200 knots but we couldn’t catch up with it,” Muiruri says, adding the plane disappeared beyond Ngong. Unshur reflects on that mission with nostalgia.

Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka, who had assumed the title of chairman of the People's Redemption Council, which planned to replace President Moi.

“You don’t know what to expect on the battlefield. But we were prepared, the task for each helicopter was spelt out, Wachira was to go in for the attack and we were the high bird to provide cover against hostile fire,” says Unshur, now the chief executive of Wilson airport-based Blue Bird aviation. “This is the true meaning of ‘I got your back.’ In the military you have to place your life in the hands of your colleague and they, too, do the same,” Wachira adds.

Onboard the buffalo aircraft destined for Tanzania was Ochuka, his deputy Sgt Pancras Okumu as well as the pilots Maj Nick Leshan and Maj William Marende. Okumu, who was among the rebels who had seized VoK, would later testify in court that the coup had begun to collapse at around 10am when loyal forces staged a counterattack to recapture the state broadcaster. ''I heard shooting and then I was informed that it was the army infantry,'' Okumu testified during extradition hearings in Tanzania on August 29, 1982. With Ochuka nowhere to be seen at VoK battleground, Okumu, too, fled back to Eastleigh airbase. Here he found Ochuka frantically calling in air strikes against government forces from Nanyuki airbase that had joined the insurgency. According to Okumu, helicopter gunships appeared over the horizon but the rebels were uncertain whose side their pilots were on. These were the choppers flown by the four Kenya army pilots.

By evening, soldiers from Kahawa barracks had secured Embakasi garrison and the 3rd battalion had recaptured Moi airbase, Eastleigh. Air Force soldiers who had been rounded up were taken to Kamiti Maximum Security Prison for interrogation. Those who were to be court-martialed were detained at Naivasha Maximum Security Prison from where they would be taken to Lang’ata barracks every morning. Muiruri, however, explains they defended the innocence of air force soldiers, particularly from Embakasi’s Gadu who had surrendered earlier on as they had no role in the coup. “They were saved,” Muiruri says, disclosing among them was Samuel Thuita, who later rose to become Air Force commander between 2014 and 2018. Unshur who was part of a six-member military panel that helped in the interrogations said the coup plotters were junior ranking officers mainly from Eastleigh and a few from Gadu, Embakasi. Unshur however regrets some Air Force officers were unfairly victimised. He cited two fighter jet pilots from Nanyuki air base who had been commandeered with a mission to bomb State House and VoK. “They performed a sonic boom at high speed to mislead their captors that they had fired but instead dropped the bombs in Mt Kenya forest. They were however arrested and court-martialed,” Unshur says, adding “In my view, they are heroes who saved the country.”

Wachira reveals the State broadcaster, VoK, which had been seized by the rebels, would have been the other target. The army pilots had flown back to Embakasi to reload missiles. He says his chopper was about to take off to bomb the state broadcasting house when his boss Kitundu signalled them to abort the the mission. “If he had been a minute late, we would have destroyed VoK,” Wachira narrates gazing in the horizon. Meanwhile, as the coup fizzled out that night, Wachira had another riskier assignment: to fly the Navy commander to Mtongwe. The military chiefs were not leaving anything to chance. But there was one problem though. They couldn’t land at Mombasa airport because there was an order to shoot down military aircraft given apprehension that rebels could be in control. The same order had been issued to Navy gunners. But Wachira was skeptical about flying into Mtongwe Naval Base at night as it was considered a treacherous flight path. He opted to call in the airport’s control tower to find out if there were Navy soldiers stationed there. And there were, ready to take out enemy planes. He sought to speak to whoever was in charge to seek clearance to land. “I have sun-ray on board,” he reported, which is code word for service commanders. He was cleared to land but the Navy commander wasn’t amused. He questioned why he had defied orders not to land at the airport. “Sir, I didn’t want to endanger your life,” he replied.

Extradition hearings

Meanwhile, the Kenyan military aircraft with the coup plotters had landed at the Dar Es Salaam International Airport. At the extradition hearings, Kenya had cited the kidnap of the two pilots as grounds to push Tanzanian to extradite Ochuka and Okumu. But Okumu and Ochuka had testified the two pilots willingly flew them. Leshan, who survived the purge after the botched coup, rose through the ranks and retired as a Lt Gen., later said Ochuka had abducted him from his house at the airbase. Leshanrose to become air force commander between 1994 and 2000. Hedied in 2021. The court rejected Kenya’s plea observing the pilots were also likely complicit. “It is highly probable that the two majors agreed to come to Tanzania in fear that the safety of their lives was in danger and the only way to save themselves from advancing infantry forces to the Eastleigh airbase was to escape to Tanzania. After all, the two majors had no ranks on them to distinguish them from other servicemen,” magistrate Goodwill Korosso ruled on September 21, 1982. The two fugitives were granted asylum. But in a surprise deal on November 11, 1983, Ochuka and Oteyo were handed over to Kenya after a political settlement between Presidents Julius Nyerere and Moi. Ochuka and Oteyo were court-martialed and hanged in 1987.

''The uprising by the air force has been crushed by our army and police,'' President Moi, then 58, announced in a broadcast on VoK radio on the night of August 2. ''This action by the air force, which took it upon itself to destroy all that we stand for, has been defeated, and, therefore, be calm wherever you are,'' Moi added.

“Ochuka failed because he had a problem of command, control and communication. He never involved many officers which was in itself was a blessing in disguise and proved crucial to scuttle the misguided coup,” explains Muiruri who went on to serve in peacekeeping missions in Iraqi and Kuwait.

No official figures have ever been released but casualties were believed to be high in Nairobi. “Former president Moi once told me that over 3, 000 people were killed,” says Wachira who was awarded a head of state’s commendation (military division) by President Moi on September 5, 1983, for his role in quelling the coup. He later flew Moi as president and in retirement.

Timelines of coup

3AM on August 1, 1982 Attempted coup gets underway with the takeover of Eastleigh airbase

4 AM: Chaos at Embakasi air base

5-6 AM: Private Ochuka and Sergeant Okumu appear at the Voice of Kenya radio to announce military takeover

10AM: Kenya Army forces launch counterattack by recapturing VoK

Mid-morning Kenya Army helicopter gunships bomb Eastleigh airbase

3PM: Ochuka and Okumu land in Tanzania in Buffalo military transport plane

6 PM to 7 AM President Moi imposes curfew on Nairobi and Nanyuki