Good athletes don’t need any approvals!

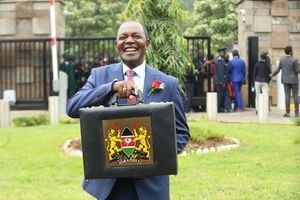

Kenya's Hellen Obiri poses on the podium after winning the 52nd Edition of the New York City Marathon on November 5, 2023.

What you need to know:

- And here’s the thing about phenomenal athletes. It’s not just about how good you think you are at the game, it’s about how good you are at the game.

- It’s about how good you are at feeling the crowd when they are with you and ignoring them when they aren’t. It is about how swept up you can get in the momentum when winning, but also how defiant you can be when the tide turns against you.

Golden girl Hellen Obiri shattered the world and brought home the New York City Marathon title and I have never received so much hate mail.

One reader challenged me to “explain to Hellen the acceptable celebratory practice expected of her, based on your standards.” Any reader who interacted with my column last Friday knows what that question implies.

I wrote about the refusal of former marathon world champion Eliud Kipchoge to acknowledge new record holder Kelvin Kiptum, and here I am, being challenged to a fight.

To answer the question, Alice, celebratory practice is about acknowledging your strengths, while also acknowledging new weaknesses.

It is about kicking open the doors on your way to victory, but also about leaving those doors open for the next person. Most importantly, it is about knowing when to stop relying on the joy of celebration as though it is a life extending serum.

This opinion is not about Eliud. I am no professional athlete, but what I know is that every athlete who is past their prime faces weaknesses that they haven’t encountered before.

Their bodies are different; they get tired faster. Age is a non-modifiable factor that affects all sportspersons. The difference is that some athletes make peace more easily with their limitations, while others live their lives denying fact.

People act like you can never forget your own name, but if you’re not paying attention, you can veer so incredibly far away from everything you know about yourself to the point where you stop recognising your name. To understand my point, you have to understand the mind of an athlete.

Don’t ask how I know the mind of an athlete. For any sports person, losing is so humiliating.The life of an athlete is a life of war.

They spend so long fighting for titles, stats and victories that they almost forget how to live during peace time. Without a world record to their name, they may not know who they are anymore.

When you are used to stepping onto the arena, with legs and arms throbbing, ready to be used, feeling the vibrations of an impending fight right in the sternum, feeling yourself turning on, every edge of your body tingling, you are likely to face a serious identity crisis when the crowd starts to scream someone else’s name, or when it is no longer possible to defend or reclaim a title, or when the time comes when you can only enter the stadium as spectator, but not as main contender.

This opinion is not about Eliud. And here’s the thing about phenomenal athletes. It’s not just about how good you think you are at the game, it’s about how good you are at the game.

It’s about how good you are at feeling the crowd when they are with you and ignoring them when they aren’t. It is about how swept up you can get in the momentum when winning, but also how defiant you can be when the tide turns against you.

Good athletes don’t need approval; they just need that medal! This article is about Hellen Obiri.