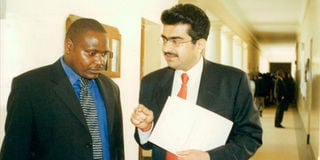

Goldenberg International architect Kamlesh Pattni (right) and his lawyer Bernard Kalove.

As the Member of Parliament for Laikipia East, I believe that I did my constituents proud by the perception that I had clawed my way into being regarded as one of the stalwarts of the ruling party, and an increasingly dependable ally of the government.

Remaining faithful to the governing philosophy of collective responsibility, I was seen as a rising defender of the policies of the government, and a party loyalist.

Given the fact that the nation was a single-party entity, getting inside the nucleus of the governing structure wasn’t unwelcome at all; it was the ultimate aspiration of serious political players on the scene then.

At the risk of coming off as overly exercised, loyalism became the withering litmus test that those with ambition beyond remaining an MP had to pass.

Find the first and second instalments of our exclusive serialisation of Francis ole Kaparo’s memoirs Calming the Storms here:

Collective responsibility

Inevitably, collective responsibility forced us to act in accordance with the mandate to explain, defend and become apologists for a governing philosophy built on the need to fuata nyayo (toe the line).

On the Floor, though, I became increasingly alarmed as our diversity inspired debate to focus on parochial rather than national issues.

Members began to be more conscious of their ethnic background rather than their mandate to act as debaters of national issues.

In that changing atmosphere, where members of questionable educational background got elected, intellectual laziness was allowed to seem acceptable, while nationalism was suddenly viewed with strident skepticism.

In that increasingly toxic atmosphere, parliamentarians saw themselves as defenders of personal interests first, then defenders of the nation. They now celebrated name-calling and beating ethnic war drums, if only to popularise themselves with an electorate that was growing progressively more hateful.

Calming the Storms book by former Speaker of the National Assembly Francis Ole Kaparo as pictured on April 19, 2024.

Leadership, to them, was no longer about planning for tomorrow, it was about ‘eating’ today. As one on the frontbench, together with other Cabinet colleagues, it was my duty to confront the growing negativism and recast Kenya as a nation of possibilities – a land where anyone could attain their dreams if they worked hard.

The patriarchal manner in which President Moi ruled the nation started to come under increasing scrutiny by leaders who felt left out of the political process.

This perception began to overshadow Moi’s genuine accomplishments as an unrelenting champion of education for the Kenyan child, and a consummate philanthropist who excelled in outreach.

The legacy of the Moi years was further tarnished by scandals of increasingly brazen corruption, usually involving such a large number of conspirators in different arms of the government that prosecution of the culprits became an impossible task.

Of these, the Goldenberg scam was the most notorious to date. It began in 1991, almost immediately after the government, following directions from the IMF, introduced measures to reform the economy and increase international trade.

One of these measures was designed to persuade exporters to deposit their precious foreign exchange earnings with the Central Bank: they would be rewarded by the government with the equivalent in Kenya shillings plus 20 per cent.

It was this scheme that fired the imagination of one Kamlesh Pattni, a one-time jewellery dealer. Claiming that Goldenberg International, a company owned by himself and former spy chief James Kanyotu, was processing gold and diamonds for export, Pattni conspired with government officials to exploit loopholes in the system.

Kamlesh Pattni, the man behind the infamous Goldenberg scandal. At age 25, he pulled off one of Kenya’s biggest thefts of the public coffers.

Forge agreement

Contrary to the prevailing laws, he was able to forge an agreement allowing Goldenberg International to earn up to 35 per cent ‘compensation’ for the company’s exports.

In truth, this was not a refund, because no money had been paid to the government under any pretext. It was theft.

The situation was made worse by the fact that little, if any, gold was actually exported from the country. Gold mining has only ever represented a tiny portion of Kenya's Gross Domestic Product, with only one operational mine in Kakamega.

Goldenberg International therefore developed a scheme for smuggling gold into Kenya from the Congo so that they could then re-export it.

As time went by, the company stopped smuggling gold and simply completed export declaration forms, produced fake hard currency deposit slips and got paid the amount on the slips, plus the 35 per cent export compensation.

It is thought that this scheme cost Kenya some Sh500 billion, the equivalent of more than 10 per cent of the country's annual GDP.

The runaway inflation that rocked the country’s economy also arose from the scandal and its associated botched deals between the Central Bank and exporters: the Central Bank was printing billions of shillings in paper money, all on the premise that the fake ‘exporters’ would bring in foreign currency and stabilise the exchange rates.

Former National Assembly Speaker Francis Ole Kaparo.

Some 487 companies and individuals were reportedly involved, many of the beneficiaries being at the highest levels of the Moi government, and even some members of the opposition.

The scandal became the subject of a report authored by the Public Accounts Committee under the chairmanship of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. The report had thoroughly covered the details of the scam, recommending that all the money that had been acquired illegally be returned and the perpetrators prosecuted. By the time it came to the House in 1994, Odinga had died, and the report had not been tabled in Parliament.

At this time, I was Speaker, and in this capacity I asked the new Chairman, Kijana Wamalwa to reconvene a meeting with PAC members and visit the Goldenberg scam afresh. They were summoned amid much protest as to why the issue should be revisited. Members voted on whether to clear the suspects in the scandal or have them prosecuted.

Four members were against letting the suspects go free, while four supported their clearance. Wamalwa, as the new PAC Chairman, broke the impasse by voting for the exoneration of Pattni and all those involved.

He also astonished the Kenyan public by recommending that Pattni be paid a further Sh2.1 billion of public money, effectively rubbishing Jaramogi’s findings. Of course, reports abounded that PAC members, including Wamalwa himself, had been compromised.

Also Read:Pattni cleared in Goldenberg scam

In the end, no-one was ever convicted for any of the Goldenberg crimes. The Attorney General, Amos Wako, notoriously failed to take effective action on the scandal, despite it having been the subject of widespread media coverage. In 2006, David Munyakei – the Central Bank employee who first blew the whistle on the scandal – died in obscurity.

One of the supreme ironies of this long-running saga was that its primary architect, Kamlesh Pattni went on to found a church, renaming himself Brother Paul.

Tomorrow: In our fourth and final instalment of the serialisation of Francis Ole Kaparo’s memoirs, Calming the Storms, the former Speaker reveals secrets leading to the formation of the United Republican Party as well as the creation of the Jubilee Alliance that went on to win the 2013 elections