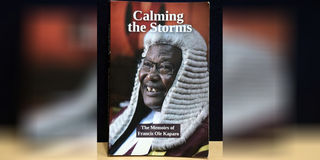

Former Speaker Francis ole Kaparo.

In this first instalment of our exclusive serialisation of ‘Calming the Storms’, Francis ole Kaparo’s memoirs, he reveals the intrigues that led to his election as perhaps Kenya’s most consequential Parliamentary Speakers, navigating a turbulent political period.

It was at the beginning of 1993 that I vied for the position that was to give me a national profile.

The process of electing the Speaker of the National Assembly was intense, zero-sum and bruising. In a rapidly shifting legislative landscape, characterised by the entrance of the opposition in law-making, State House and other key organs were keen to safeguard whatever influence they could exert in the nation without facing too much by way of scrutiny.

To be elected Speaker under the standing orders, one was required to garner two-thirds of the votes in the House.

If that figure was not reached in round one, then the process was to be repeated. If, on the second round, nobody garnered the two-thirds of the votes, a third round of voting was undertaken.

In this round, whoever won by a simple majority was declared the Speaker of the National Assembly.

The new House then comprised one 110 members from the ruling party, Kanu, and 100 representing the totality of opposition parties, all of whom were elected members.

Under the laws of the Constitution, the President was entitled to nominate 12 persons as members of the National Assembly, including myself.

The house, therefore, had a total strength of 222 members, excluding the Attorney-General, who was an ex-officio member.

Of these 222 members, 121 were present for the voting. As a candidate, I could not vote.

The voting was strictly on party lines, and for that reason, nobody could get the requisite two-thirds majority votes to win.

The lobbying and jostling to keep the troops in check was intense on both sides.

My name was proposed by none other than the Member for Baringo Central, who also happened to be leader of the ruling party, KANU, and the Head of State: President Daniel arap Moi himself.

Calming the Storms book by former Speaker of the National Assembly Francis Ole Kaparo as pictured on April 19, 2024.

He was seconded by Prof George Saitoti, the country’s Vice-President. On the basis of their strong voice, the ruling party settled the matter of its candidate. I would battle it out with whomever the opposition had chosen as its candidate for the position. This wasn’t going to be easy!

Genesis of proposal

I suspect that by the time President Moi proposed my name to become Speaker of the House, he had progressively come to terms with the growing restlessness in Kenya as the nation’s elected politicians struggled to understand their new roles in an open society.

He had also witnessed my resolve at Kasarani Sports Complex, back in December 1991, when I was still in the rather junior post of Assistant Labour Minister. There, at the KANU Delegates’ Conference, I was the foolhardy one who went against the grain and urged him to let Kenya revert to a multi-party state. On the first morning of the conference – December 4 – I had watched in dismay as sycophants fell over themselves, urging the Head of State not to heed the call of those calling for plurality in Kenya, and to ignore the pressure piled on him by the West.

Against them was a group of agitators, fronted by the likes of Kenneth Matiba, Martin Shikuku and Raila Odinga.

Inspiring other disaffected patriots throughout the country, they had in recent years provided a chorus of shrill voices demanding fundamental change in the governance of the nation.

Participatory democracy and political accountability was their watchword.

Delegates at Kasarani urged the Head of State to ignore them. Their chorus was deafening.

KANU is a strong party!

We are a sovereign nation!

You cannot fell a Mugumo tree with a razor blade!

The opposition is serving foreign masters!

Money has been poured!

And that was the first day. On the second day of the conference, I had my chance to address the gathering – just briefly – after I stood to seek the attention of the Master of Ceremonies, the then Deputy Speaker, Kalonzo Musyoka.

The poignancy of my words ensured that I was to be the first and last speaker of that fateful day. After paying the necessary homage to the strengths and virtues of the ruling party, I urged the Head of State to let us face our detractors, as I was certain we would vanquish them at the polls and outplay them in the National Assembly.

As soon as I was done speaking, President Moi stood up and adjourned the meeting. There was dead silence. Kaparo was finished!

In that moment, I faced a barrage of intimidating feedback. The only compliment I got was from Philip Leakey, who at that time was the Assistant Minister for Natural Resources and MP for Lang’ata. Not too sure what would eventually happen to me, but delighted I had spoken strongly on the matter, Leakey said: “My friend, you have four balls!”

“I have twelve. I keep the others in my pocket!” I fired back.

I recall that during that tense period of adjournment, William ole Ntimama shook his head as he came to our delegation. Addressing members, but obviously seeking to catch my ear, the kingpin of Maasai politics said: “I thought this fellow was smart. Sorry to say he is just another fool.”

It was a chilling putdown. It was the loneliest adjournment I have ever had to endure. Nobody wanted to sit next to me, let alone engage in any conversation. As far as they were concerned, my goose was cooked. I had challenged the status quo and failed to toe the official line. I had departed from the beautiful chorus of those who had urged intransigence just the day before; those who had poured cold water on the mischievous surrender of cynical Kenyans to their foreign masters.

Nominated Member, Mark Too, caught up with me and warned: “At one o’clock, you will be dismissed!”

“I heard of my appointment as an Assistant Minister over the one o’clock bulletin. I’m not afraid to hear of my firing over that same bulletin!” I told him.

However, it was Job Moika Kasaine Lelampaa, Member for Samburu East, who captured the mood of the moment. He edged to where I stood alone and said: “I think you were misquoted.”

“I can’t misquote myself!” I curtly replied.

Upon resumption of the session hours later, Moi came back with a written speech. He sought to address fellow Kenyans and the international community. He agreed with delegates that multiparty politics was a danger to cohesion, but was inclined to allow the repeal of Section 2A of the country’s Constitution and a reversal to plurality – in the interest of Kenya.

At that moment, you could hear the drop of a feather. The President explained that he did not want Kenyans to continue suffering under punishing sanctions on account of a single party state. He was ultimately liberating Kenya!

The moment he finished speaking, those who had urged him to clamp down on dissension clapped and tripped over themselves to congratulate him. I don’t know what he thought of this circus of foolishness, but I couldn’t help but wonder about the clowning. How could men and women who had – barely a day earlier – urged one position, switch so casually to another so shamelessly? It was embarrassing.

“If you knew what the Head of State had in mind, why didn’t you tell us?” Mark Too asked, displeased.

The President never called to talk or congratulate me for the bravery I displayed at Kasarani, but I knew that he greatly appreciated my role, because three days after that event, he appointed me the Minister for Industry.

And as usual, I heard of that appointment over the radio as I was driving back to Nairobi on a Sunday, having spent the weekend with my constituents in Laikipia.

More than 30 years later, I look back at that conference and regard it as the defining moment of my career.

It was with his recollection of that short speech on my CV that President Moi proposed my name for Speaker, and I thus became the only candidate that KANU was going to endorse.

Order! Order! Order!

And so the voting for the Speaker began. It was a strict party-line vote. In those grim days, there were no centrists in Kenyan politics – it was us versus them. Open hostility was on display everywhere one looked. MPs on the government side never said hello to those in the opposition, and members on the opposing side never said hello to those on the government side – a sad state of affairs that prevailed for almost a year.

In that moment of palpable anxiety caused by the high tension of possibly winning and becoming the leader of a deeply polarised House, I had to keep focused by looking at the bigger picture.

However, as that picture spread out across the hallowed historical screen of the House, it displayed the hatred members now had one for another. It projected images of crippling dysfunction.

Seeing thus that I was probably going to win by a slim majority to become Speaker, I wondered how I was going to make the situation work.

Matters were not helped by the fact that three rounds of voting were required, because the constitutional threshold of two-thirds of the votes cast was not within reach for me. (This later made it intimidating for me, on the first day, to call the House to order). In that moment of frailty, I harkened back to the inspiration offered by Sir Humphrey Slade’s example, and decided that my guiding principle would be to do only what was legally and morally right; act within the law and adhere to the rule of parliamentary standing orders. I had to keep the public good in constant focus and endeavour to safeguard the public interest, not only the interests of the larger blocs in the House.

My moment of fascination, after being elected, ended when Opposition Leader, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, to my left, and George Saitoti, to my right, walked up to me, along the Speaker’s Walk, and congratulated me. They then led me to the entrance of the august House, in keeping with the traditions of Commonwealth parliamentary procedure. There, the Chief Sergeant-at-Arms shouted: “Mr Speaker!”

However, as I came to learn, the National Assembly was not what Kenyans made it out to be. It was a place the raw tribal sentiment manifest in the nation at large found a mouthpiece, duly reverberating in the coverage of the print and electronic media. With editors, reporters and key media owners who appeared partisan, Kenyans were fed on a constipating diet of unbalanced and counter-productive reporting.

On that floor, I was stunned by the way some of the members sent by voters to represent them let down their guard as they discussed sensitive matters. As the Speaker, it was my duty to steer discourse back to acceptable conduct by projecting my voice above the rancour, sometimes having to kick members out of the fiery chamber.

Indeed, there were times I found the atmosphere within Parliament much more harmful to the containment of political temperatures in the nation than we cared to admit. It was in moments like these that I stood firmly on principle and ensured that orderliness was trumpeted from the National Assembly.

From my elevated Chair, I repeatedly warned Members of the imminent danger of national strife if sweeping ethnic condemnation and attempts to vilify certain communities was not brought to a halt. Given the current state of affairs in our nation, my fears have regrettably come to pass.

Ethnic divisions in the land are at an all-time high and it is getting worse by the day, fuelled by the recklessness of pronouncements on the social media and the tactlessness of a younger generation steeped even deeper in tribalism than their forbears!

I felt uneasy and sorely intimidated the first time I shouted “Order! Order! Order!”

If you’ve ever been a student of English, you will realise at once that the word, as it is used by the Speaker, presupposes the absence of order. It envisages the need to restore calm in an otherwise deteriorating situation that could get totally out of hand. By the time I assumed my position as Speaker, I had been in Parliament long enough to understand the tricky dynamics at play on the floor, and to realise that they could paralyse debate. However, I still found it incredible that in a place members were called “honourable”, there was also need to repeatedly shout: “Order!”

I look back and realise that the word “Order” has held a far deeper meaning in my life than I realised when I was the holder of that solemn office. The level of disorder – occasionally reflected in the House – was unnerving, stunning, deeply revealing and sometimes dispiriting.

The only weapon I had to calm the raging waters was the word “Order”, derived from the authority vested in me through Parliament and the Standing Orders instituted by the House itself.

Relying on that solemn authority, I sought to establish a positive atmosphere in which members felt valued and their contributions consistently respected, in spite of being in different parties. I relied on a cocktail of command, wit and humour to calm matters whenever there was a crisis and tension, but came to discover that humour and wit were far more effective than commands.

Order, therefore, became synonymous, not just with a call to deep reflection, but with a call to safeguard the only heritage we could identify as ours!

I worried about the remuneration of members and the staff of the National Assembly. I wanted improved terms of services for them so that they would end the undignified habit of begging from the President and Cabinet ministers.

We, thus, worked out a scheme in which the pay scale was raised, terms of employment were improved, ethnic representation in staffing was factored in, and medical insurance was provided.

We also sought space for a library and for the development of a health club or fitness facilities, all in the interest of fostering a healthy workforce.

- Tomorrow in the Daily Nation, how Francis ole Kaparo combined open sycophancy and demonstrable pragmatism in his duties as minister under President Moi.