How we overcame our fears and climbed to the top of Mt Kenya

What you need to know:

- The climb being for August — the last holiday period before the A-Level exams — was too close for most girls.

- The author captures the students’ excitement the first morning they wake up to witness a snowfall in Teleki Valley.

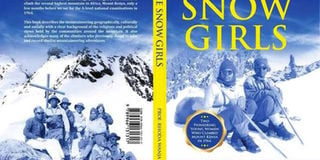

Title: The Snow Girls

Author: Rhoda Wanja Thairu

Publisher: Anvil Publishers Limited, 2019

Pages: 198

Reviewer: DOROTHY KWEYU

The book’s blurb puts it succinctly: “an adventure story”. It describes how the author and a classmate, Hannah Njoki, “dared to climb the second highest mountain in Africa, Mt Kenya, only a few months before we sat for the A-level national examinations in 1964.”

Rhoda Wanja Ng’ayu and Hannah Njoki Kahiga — Form Six students at the African Girls High School (today’s Alliance Girls) — prove to be, indeed, adventurous in more than one way.

CONQUER MT KENYA

They are the only girls in a class of 12 to answer headmistress Mary Bruce’s call to join a predominantly male group of students from Alliance, Thika and Jamhuri High, all boys’ schools, on a mission to conquer Mt Kenya.

With them is a young female teacher, who had only just joined the school from the United Kingdom.

In a heart-warming foreword to The Snow Girls, Edward Tiagha expresses his fascination with the mountain that had him spellbound as “a mysterious source of knowledge and mysticism” as he grew up in his native Cameroon.

Hannah met Edward in New York in 1969 — five years after the mountain climb adventure. It is evident from his foreword that Hannah Njoki’s adventurous spirit won over her future husband.

Njoki, who like her friend Rhoda, grew up in the Mt Kenya region, fills the mystical void that Edward Tiagha experienced while growing up.

The Kikuyu people, Tiagha writes, “had depended on the mountain as a shelter and home of their ancestors, a place where liberation oaths were given to the fighters, a place where young men were circumcised, a place where young women were circumcised, a place that trained both male and female leaders in the fight for independence, a place that generated serious thought about nationalism, ownership, entrepreneurship, and a place that bred fearless African leaders.”

CLEAR WATER

Using repetition creatively is a feature Wanja employs throughout the book. For example — and as if to mimic Samuel Taylor Coleridge in his “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” — she writes: “There was water, water everywhere; very cold and clear water was flowing to the lower parts of the mountain. This was water that had thawed from precipitated snow.”

The repetition of ‘water’ — and other words in the book — has a captivating poetic effect that mitigates the sombre mission that got tougher the higher the band of adventurous students scaled the mountain.

In terms of sentence length, a journalist’s stock concern, the 69-word extract from the foreword exceeds what professional newspaper editors would accept.

But then again, this is a book, and Tiagha exercises poetic licence. While it fell on him to write the foreword, Tiagha’s style achieves more than that; the powerful foreword serves to glue the reader to the book, compelling them to read on.

The foreword also makes an important nexus between co-curricular and classroom activities. He writes: “They climbed up and climbed down successfully. In so doing, the girls entered the record books as the first two indigenous Kenyan girls to climb the third highest peak in the country.

They went on to conquer the world and became pioneers in their various fields.”

DULL BOY

This is an important point that the book brings out, not just from the adage that “all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”, it also affirms the importance of raising children in an all-round manner.

Then as now, so much premium is laid on swotting that although the girls’ initial reaction to the Mt Kenya expedition seemed positive to Miss Bruce, only Wanja and Njoki stayed the course.

The climb being for August — the last holiday period before the A-Level exams — was too close for most girls.

Both the author and her friend, Njoki, who has since died, hold doctorates in their respective fields, testimony that co-curricular activities do not undermine classwork, but rather reinforce it.

The author captures the students’ excitement the first morning they wake up to witness a snowfall in Teleki Valley — an experience only their team leader, a Mr King’ori, and the British teacher, were acquainted with. The phenomenon is such that the cooks for the day — every climber had his or her turn in the kitchen — make a quick job of preparing breakfast so they can marvel at the spectacle.

ADVENTURERS

But the Teleki Valley also brings a reality check to the team of adventurers. Five of the boys find themselves unable to proceed with the climb. The enthusiastic girls find this incomprehensible, seeing they had already come that far.

It was not easy, though. The climb gets trickier the higher they go, and the author captures the sense of adventure as she imagines what would happen if one missed a step.

The climbing and the sites they see provide room for reflection: Why did the peaks of a mountain that’s of great significance to the Kikuyu have only Maasai names — Batian (the highest), Nelion and Point Lenana?

Their reflection on the significance of the mountain not only of significance to the Kikuyu but also to the Kamba raises the issue of Mzungu ignorance.

“The wandering explorers or geographical spies of the time did not know the names of various places and did not care to ask the local inhabitants of the country around the mountain,” the author writes. She shares what she had heard from her parents — that the tallest peak was called ‘Nyathi’, the commander, the second highest peak, Utheri or the sun, and the third one Kiahu, the offshoot.

CULTURAL RESOURCE

The book is thus not just an adventure story but a great social-cultural resource. That they are able to query Mzungu names testifies to the learners’ critical thinking. Getting to point Lenana — the highest they could reach — was not a walk in the park.

Indeed, more students dropped out, although the girls made it to Point Lenana. On the flip side, the author could surely have secured design backup.

The graphics are so amateurish that they detract from an otherwise highly informative and educative book.

I suggest that once the initial stock runs out, the author should invest in a good graphic artist to put some polish into the graphics.