A hug for Chris Wanjala and all the non-fiction writers

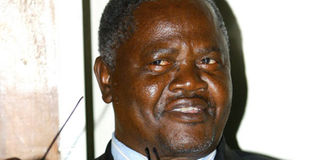

Prof Chris Wanjala. I owe Wanjala, a hug. In fact, it’s been pending for over five years now. When we last met, in the hall of a commercial bank in Anniversary Towers in early 2009, he was just going to envelop me in his characteristic bear hug, when I held out my hand, maybe with a faint scream, asking him to hold off! PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- Since then, I have only been “following” Chris Wanjala on social media. I am proud of him for being one of the few of our generation in East Africa not to be intimidated by technology, especially ICT, and also for his indefatigable and uniquely articulate engagement with all matters human and humane.

- But what brought Christ Wanjala back to my mind are the recent posts on social media regarding his activities at the Kenya Non-Fiction and Academic Writers Association. Strangely, I hadn’t heard of this important organisation before!

I owe my Bakoki, Chris Wanjala, a hug. In fact, it’s been pending for over five years now.

When we last met, in the hall of a commercial bank in Anniversary Towers in early 2009, he was just going to envelop me in his characteristic bear hug, when I held out my hand, maybe with a faint scream, asking him to hold off!

I had to dispel his bewilderment with elaborate explanations of how decrepit I felt, and how I didn’t want him to cause a medical emergency in those inhospitable surroundings.

The surroundings were, indeed, inhospitable, as I had just been told that my account had dried up, and they had closed it, killed it, or whatever they do to such accounts. There are few things worse than being sick and broke.

Since then, I have only been “following” Chris Wanjala on social media. I am proud of him for being one of the few of our generation in East Africa not to be intimidated by technology, especially ICT, and also for his indefatigable and uniquely articulate engagement with all matters human and humane.

He has also consistently said positive things about my humble literary practice and, although I know some of them are a little exaggerated, I’m inclined to believe them. After all, a little appreciation never did anyone any harm.

FOLLOW THE BEE

But what brought Christ Wanjala back to my mind are the recent posts on social media regarding his activities at the Kenya Non-Fiction and Academic Writers Association. Strangely, I hadn’t heard of this important organisation before!

But then, I noticed that even my sister, the indefatigable “minister” (servant) of the arts, Margaretta wa Gacheru, was wondering how to get in touch with the association.

Well, Margaretta, follow the bee and eat honey. The Non-Fiction Writers are sitting pretty and tight on the third floor of Viking House in Westlands and some of their phone numbers are 0724711562, 0729145836 and 0722837731.

I will certainly drop in on them when next I am that side of town, and maybe I will catch up with Chris Wanjala there.

What doesn’t surprise me, however, is that Wanjala should initiate this kind of organisation since he is one of the most knowledgeable and serious people about literature and writing in our region.

As such, he knows that fictive literature, which we tend to privilege, is only a tiny fraction of the main business of texts. Indeed, most of the texts that we produce or have to respond to are patently non-fiction.

Secondly, Wanjala knows that all texts, whether of fiction or non-fiction, are seriously important. Indeed, as the football coach told his team, they are not just a matter of life and death. They are far more serious.

Some sections of society, for example, have subjected others to slavery and exploitation for millennia, just because some “holy text” says, as the exploiters claim, that those others have to be their slaves, “hewers of wood and drawers of water”.

Others stone, bomb and behead those that they regard as “infidels and apostates” because they think that’s what their holy writ prescribes. Constitutions, too, over which such epic battles as referenda are waged, are plainly texts.

The main problem about these situations is that many of the touted promises, prescriptions or provisions of the writings are often gross misreadings and misinterpretations of those texts.

PROFOUND RESPECT

In Christianity, for example, many so-called churches have been turned into dinning halls (and I’m not talking about “dining” but dinning, noise-making madhouses), with every self-proclaimed prophet yelling about what “the Bible says”, when very few of them have ever engaged that text with the respect and seriousness that it deserves.

Thus, experts like Prof Wanjala know that the only measure that can save texts, and ultimately humanity, is thorough, competent and conscientious reading and interpretation.

This is probably the fruit of the kind of education and training that Wanjala and we, his agemates, received in handling texts. As disciples and apprentices of the pioneers of “Practical Criticism”, mostly Cambridge men, like I.A. Richards and F.R. Leavis, or of their immediate students, we were persuaded to treat all texts with the most profound respect, and never to take anything for granted in a text.

The enterprise was to establish and promote literary and textual study as a professional discipline and practice with basic principles and a strict method that systematically and fully accounted for the competent reader’s response to a text, whether fiction or non-fiction.

You were not expected to comment on a text until and unless you had subjected it to an “astringent scrutiny”, in the words of F.R. Leavis, under whom I was privileged to study for a term in 1966.

The hugely influential critical journal that Leavis founded and edited for 30 years was, not surprisingly, called Scrutiny.

PRACTICAL CRITICISM

What the practical critics, or “new critics” as they were called in America, set out to do was to raise literary scholarship above the decadent, dilettante and amateur ramblings, based on vague notions of “taste, talent, culture and inspiration”, that dominated literary discourse in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and practise it as a precise, principled discipline based on concrete and objective evidence.

This is underlined in I.A. Richards’ “manuals”, Practical Criticism and Principles of Practical Criticism, on which our generation was raised.

As it turned out, this upbringing stood us in very good stead in East Africa as we struggled to preserve the integrity of the literary discipline in the face of the rabid ideological onslaught to which it was subjected through most of the 1970s and 1980s.

Wanjala felt it was necessary to take “Standpoints on African Literature”, a title of one of his early texts, but these standpoints were not to be based on raw emotional or ideological excitement but on the principled study and scrutiny of African texts.

Doesn’t he deserve a hug for that, however unsystematic and unprincipled?