Publisher laments about Kenya’s new ‘literary desert’

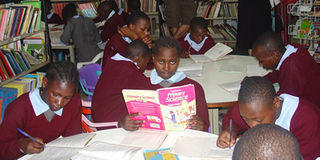

Publishers are literally struggling to scout for good Kiswahili manuscripts. Photo/FILE

It is almost over four decades since Taban lo Liyong declared East Africa a “literary desert” in his often quoted book titled The Last Word.

Despite that, many writers – both young and old – are churning out literary works year in year out. Therefore, the interpretation of Taban’s ‘‘curse’’ seems to have shifted from the bane of few literary works in the 1960s to the many but ‘‘mediocre’’ manuscripts currently being delivered by authors to publishing companies.

The East African Educational Publishers (EAEP) publishing manager, Mr Kiarie Kamau, says the worst hit area is Kiswahili literature where publishers are literally struggling to scout for good manuscripts.

Presenting a paper titled Publishing of Literary Works in Kiswahili: The Paradoxes and The Need for a Paradigm Shift, at the recently concluded Chama Cha Kiswahili Cha Taifa (Chakita) international conference in Nairobi, Mr Kamau lamented that out of 10 presented manuscripts, nine of them are written in English and one in Kiswahili.

He further said that even the few Kiswahili manuscripts received for evaluation are poorly written.

“This clearly indicates that creative writers in Kiswahili have not come of age compared to their English counterparts,” the publisher said.

Mr Kamau attributed the problems and paradoxes bedevilling Swahili writing in the country to two major sources – the author and the publisher.

“Whereas the canonical procedures of getting published have recently produced some fine works in Kiswahili, the Kenyan Kiswahili literary scene has seen the emergence of a certain category of writers keen to write creative works using literary theories as the base,” he said.

He said that more often than not, authors who force theory into their works end up writing for elite readers who know and understand the theories.

Mr Kamau challenged Kiswahili scholars, who are also authors, to draw the boundary between creative works and academic ones.

The publisher also lamented that most Kiswahili creative works presented to publishers for assessment have serious deficiencies in the areas of building a cohesive plot, developing strong characters and giving powerful descriptions that leave vivid images.

Mr Kamau, a Swahili scholar, further ruffled the feathers of creative writers by attacking their use of Kiswahili language. “There is another category of Swahili literary writers who wallow in unleashing bombastic Kiswahili terminology in their works.”

Such writers, said Mr Kamau, seek to impress rather than express themselves.

He noted that such writers are bent on the belief that good writing is judged by how much a writer has the grasp of the most difficult Kiswahili words, some of which are lifted from various Swahili dialects and are suitable only in the poetry or ushairi genre.

The other malaise afflicting Kiswahili creative writers and writing, according to Mr Kamau, is what he termed ‘‘turf wars’’. These are the differences among most Kiswahili scholars and writers which are not necessarily the product of differing literary points of view, but emanate from petty intellectual jealousies.

Mr Kamau revealed that some Swahili authors who are given manuscripts to assess and provide reports to publishers turn out to be “enemies within and without”.

Such reviewers, said Mr Kamau, often submit negative reports on the manuscripts they are given when they somehow get to know that the work belongs to a fellow academic whom they don’t see eye to eye with.

However, Mr Kamau did acknowledge the fact that since mid 1990s to date, more Kiswahili authors have arrived in the scene to boost the efforts of the older generation of writers such as Jay Kitsao, Chacha Nyaigotti Chacha, Katama Mkangi, Kithaka wa Mberia, Alamin Mazrui and Kimani Njogu.

The names of such upcoming writers include Mwenda Mbatiah, John Habwe, Kyallo wa Mitila, Ali Hassan Njama, Hezron Mogambi, Ken Walibora, Clara Momanyi, Timothy Arege, and Bitugi Matundura among others.

Publishing institutions were also blamed for being profit-oriented at the expense of publishing literary works.

Enock Matundura is the author of Mkasa wa Shujaa Liyongo