Rogue ambassadors: It did not start with Ranneberger

Former US ambassador to Kenya Michael Ranneberger. PHOTO / FILE

What you need to know:

- They have been called cowboys, labelled racist and some even ordered to exit Kenyan territory within days. They have been accused of all manner of plots, including scheming to topple governments and conspiring to lord over the natives, yet these daring men still remain keen on their missions, risking both their diplomatic integrity and continued stay in the country

In 1991, smack in the middle of a sore diplomatic dispute between the United States and Kenya, Ndolo Aya, Nairobi’s then Foreign Affairs Minister, described Smith Hempstone, Washington’s rough-edged point man to the country, as a racist who had “contempt for Africans” and the attitude of a “slave owner”.

Aya had summoned the ambassador for a private scolding, and told journalists later that he had told Hempstone how he regretted the fact that the United States had chosen “a man of his calibre to represent his country”.

But the ol’ chap Hempstone (he died in 2006) was not the type to suck up punches without hitting back.

“I don’t know if supporting human rights and multi-party democracy makes me a racist or not. But it’s a little hard when both sides of the equation are black,” he said, referring to the Government and the opposition in Kenya.

Joining Hempstone in heaping the diplomatic pressure on the Moi regime for insisting on a single-party state was then German ambassador Bernd Mutzelburg, who had been recalled for consultations on how to protest against the “increasing brutality with which the Government of Kenya was going against the opposition movement”.

Asked recently by a Business Daily writer whether his showdowns with the Moi regime bore any fruits, Mutzelburg regretted that some of those who championed democracy, accountability and transparency in the 1990s had turned against these values after making it into the government at the end of 2002

Fast forward to 2010, and the cliché that the more things change, the more they remain the same begins to acquire some credibility.

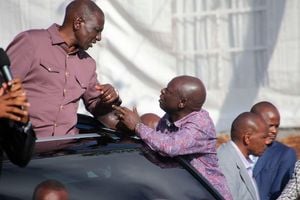

This time, US Ambassador Michael Ranneberger’s neck is the on the chopping board. President Mwai Kibaki and Prime Minister Raila Odinga have chided him publicly following allegations that he is organising and bankrolling the youth to take over from the old guard.

Ranneberger’s brand of activism was bound to land him in hot soup soon or later anyway, for daggers are likely to be drawn against you when you ‘receive’ political defectors, are made an elder of this or that community, and are vocal against perceived human rights transgressions in your station. Kenya’s political landscape, after all, relies heavily on the first two of these.

Some MPs want Obama to recall his man in Nairobi for his opposition to the re-opening of the Charterhouse Bank, despite the plans being nodded through by a parliamentary committee. The American backlash, as expected, has been to bar some of the MPs and their families from travelling to the US.

The sharpest sting from the ambassador, however, is the handing over of a dossier containing the names of MPs suspected to be deep in the narcotics business to the Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission.

These ‘cowboy antics’, however, didn’t start with Ranneberger, who, according to WikiLeaks, also thinks Kenya is a swamp of corruption. Washington’s postings to Nairobi have always dabbled in Kenya’s politics.

William Atwood — no, he was not roguish in the Ranneberger sense — was the first US ambassador to Kenya. His brief during his tour of duty (1964 to 1966) was clear: Prevent Kenya from falling in the hands of communist Russia and China.

President Lyndon B Johnson sent Atwood to Nairobi during the Cold War era, when Russia, China and Eastern Europe were pitted in a bitter struggle for global supremacy with capitalist North America and Western Europe.

Capitalising on the sharp ideological differences between the socialist Vice President Jaramogi Oginga Odinga and capitalist President Jomo Kenyatta, Attwood ensured that the capitalist camp, led by Kanu Secretary General and Minister for Constitutional Affairs, Tom Mboya, outwitted the communists.

The envoy later wrote The Reds and the Blacks, which, though not very critical of the Kenyatta regime, was banned in Kenya. The book portrays Jaramogi Odinga as a reckless politician accepting military aid from the defunct Soviet Union and China, only for the Kenyatta regime to reject it.

The gong for the best political ambassador, however, goes to Smith Hempstone for openly throwing his weight behind the crusade for the resumption of multi-party democracy in Kenya.

Hempstone claimed that his love for Africa was stirred by the renowned American author Ernest Hemingway, on whose hotel room he had turned up uninvited while honeymooning in Venice back in 1954.

“Been to Africa?” Hemingway is said to have asked him. “You ought to go. Africa’s man’s country. Fish, hunt, write. The best”. (Rogue Ambassador: An African Memoir, 1997)

This apparently long-held dream came to pass in 1989, when Hempstone was appointed by George H W Bush to Nairobi. The man took up his posting with gusto, incurring the wrath of the Moi regime.

Avoided served drinks

In Rogue Ambassador, the former Washington Times editor-in-chief claims that “the Government of Kenya, at the highest level, allegedly was planning to kill me”.

To avoid being poisoned in social functions, he is said to have avoided served drinks in preference to the bar, selected hors d’oeuvres from the back of the tray and carried vials of a strong emetic (a vomit inducing substance).

The final straw broke when, by either coincidence or providence, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga and other heavyweights launched the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (Ford) the very same day that the ambassador was delivering a pro-democracy speech. This confirmed Moi’s fears that the American was planning his downfall, and, from then on, it was bare-knuckle boxing.

But he wasn’t wily enough for Kanu, which gave a fragmented opposition a walloping at the 1992 polls, triumphing over the struggling opposition by a 37 per cent margin.

Even during a televised farewell party to the nation, the two had not time for pleasantries, with Moi telling Hempstone: “I had nothing personal against you... until you sided with the opposition.”

Serving in the same period as Hempstone, Norwegian envoy Niels Dahl was an ardent supporter of the opposition. But, unlike any of his kind in the country’s history, Dahl had his tour of duty cut short when President Moi, while addressing a public forum in 1990, ordered him and his entire staff out of the country in seven days.

Besides being the de facto leader of the “Scandinavian block” of ambassadors who supported Hempstone, the Norwegian seemed to have angered Moi by attending the court arraignment of Koigi wa Wamwere, then a leading “dissident” on trial for allegedly planning to overthrow Moi.

The president was particularly annoyed by Norway for offering political asylum to Koigi and other government critics. After the envoy and the entire embassy officials were sent packing, diplomatic relations between the two countries were not restored until 1994.

Although he lacked Hempstone’s fire in the belly, Ambassador William Bellamy had his share of drama during his three-year tour of duty in the country.

He oversaw the cutting off of US anti-corruption aid to Kenya after Permanent Secretary for Governance and Ethics in the Office of the President John Githongo resigned from government and sought refuge in the UK in 2005.