Judiciary and informed citizenry the vanguards of our constitution

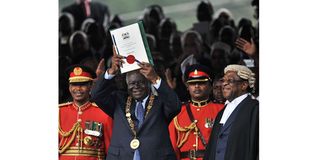

President Mwai Kibaki lifts up the new Constitution soon after its promulgation at the Uhuru Park grounds in Nairobi on August 27, 2010.

What you need to know:

- The eleven years since its promulgation is the longest time in the history of post-independence Kenya without a constitutional amendment.

- Of all the arms of Government, perhaps the Judiciary remains the only one that has internalised the essence of what the promulgation of eleven years ago meant.

At just eleven years since its promulgations, the constitution of Kenya is a young one. Despite its tenderness of age, the constitution has shown some amazing resilience.

The latest show of this resilience was demonstrated last week when the Court of Appeal struck out as unconstitutional a Bill (The Constitution of Kenya Amendment Bill, 2020) which intended to make several amendments to the law in one fell swoop. The court found that the amendments would dismember the constitution.

Before this amendment Bill, there had been almost twenty other unsuccessful attempts at amending the constitution. Despite the fact that the eleven years since its promulgation is the longest time in the history of post-independence Kenya without a constitutional amendment, this status of affairs is not out of respect for the constitution itself.

This resilience of the constitution must not be mistaken for its maturity. Quite on the contrary. The constitution of Kenya 2010 is still nascent and unripe in several respects. Put another way, the constitution is yet to deliver to citizens the full benefits of its values and aspirations.

This has happened in a number of ways.

Although the constitution was promulgated to much fanfare and immense popular support following the referendum that was held on August 4, 2010 — and had within it fairly clear and arguably tight schedules for its implementation with an outside margin of five years for complete implementation — the charter is not at its full throttle.

The first reason for the frustrated efforts at implementation is that the adoption of the document as a charter of governance was never by consensus. There have been persons, institutions and structures that have gone out to frustrate the full bloom of the constitutional architecture. This has been done in a number of ways. The first way is by deft explanation of the constitution as unrealistic, expensive and its expectations foreign and unattainable.

This is a situation where the dictates of the constitution are simply side-stepped and ignored.

Morality on public ethics

The best example here is the manner in which what was ideally the centerpiece of the constitution has been brought to nought. Chapter six of the constitution, which was to usher in a new national political and citizenry morality on public ethics, has simply ground to a halt and practically been repealed by disobedience and inaction. There are simply no efforts to uphold the ethics and integrity imperatives that this chapter was meant to herald within the national governance fabric.

The responsibility for this does not lie in one place. It is shared by the citizen, who elect into office persons who clearly fall short of the expectation of integrity that this chapter demands. They have elected or allowed the appointment of public officers who think that the dictates do not apply to them. Starting from the elections of 2013, the elected administrators at the national and county government levels literally buried the chapter.

The second manner in which the implementation was frustrated is by vacillation in the hope that the steam for implementation will dissipate and disappear. In this way, style takes precedence over form while the authorities that are the means to bring into place the institutional makeup that will support the constitution’s values simply pay lip service to it , if at all.

An example is parliament’s failure to implement the requirement that at no more than two-thirds of the legislature should be composed of one gender. Instead of the genuine endeavors to effect this through legislation, parliament spent its time telling Kenyans how this is too complicated and unachievable by mere legislation.

The third approach of stalling implementation is by open defiance of the constitution’s values. The deluge of disobedience of orders by the executive and parliament have eroded the rule of law as the bedrock of republican constitutional principle that the law applies to all.

But even more poignant is the fact that a constitutional requirement that where parliament fails to implement the gender rule mention above, then it ought to be dissolved by the President on the advise of the Chief Justice. This advise was given almost a year ago and has never been acted upon, thus creating an alliance of non — compliance between the two branches of government.

Essence of the promulgation

These are but a few examples to show that while the constitution is resilient, there is no guarantee that this will always be the case.

Many believers in the rule of law and defenders of republican constitutionalism must worry about this. There is a blip in the constitution’s survival because it has almost no support from the Institutions that are meant to uphold and defend as evident from these examples.

Of all the arms of Government, perhaps the Judiciary remains the only one that has internalised the essence of what the promulgation of eleven years ago meant. It is the only branch that can be said to be in sync with the values principles and dictates of the constitution, hence the angst it attracts from politicians, the other arms of government and sections of the citizenry not committed to the new constitution.

The other upholder hero of this constitution is the ordinary citizen. A section of Kenyans have taken the mantle of reminding the country that there is a new constitution and which must be the blueprint of governance and institutional design within the country.

These people, derided as activists, have kept the flame burning by their constant call to the better angels of Kenya as dreamt in the constitution. They have tirelessly instituted suits seeking implementation and call out unconstitutional action within the courts.

And the courts, to their credit, have accepted the petitions of these oft-maligned Kenyans by giving its imprimatur to call back the rest of the country to the dreams of August 27, 2010.

The lessons of the last eleven years are stark — active and informed citizens are the oxygen that the constitution needs to grow and embed a functional republic in the way that the constitution envisages.

It is only because of the citizens and the Judiciary that we can say that the constitution proclaims liberty for all throughout the land and for all the inhabitants.