The fearless, unparalleled Philip Ochieng

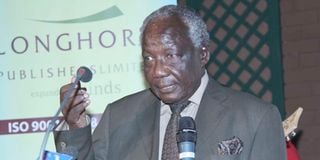

Philip Ochieng during the launch of his biography written by Liz Gitonga-Wanjohi at The Stanley on August 21, 2015.

There was outpouring of grief and appreciation upon news of Philip Ochieng’s death on Tuesday evening. Despite his imperious and uncompromising insistence on quality, Ochieng was loved for his exceptional brilliance and humanity.

The irony, of course, is that while Ochieng was the unparalleled maestro of the trade, his fearless commitment to an egalitarian ideology and justice made him unpopular with those who run our country.

While exceptional tributes flowed from Kenyan leaders, some would have wanted him behind bars rather than at an editor’s desk.

Despite his dissenting politics, Ochieng’s unmatched range of skills and ferment left newspapers no choice but to hire him to senior levels. But it was invariably in positions he could not direct the paper’s political orientation or news coverage.

As the Nation Media Group (NMG) Editorial Director Mutuma Mathiu wrote in his revealing portrait: “the newsroom was his habitat. He loved the adrenaline of news.” Yet Ochieng was barred from the “newsroom” he loved, with media managers going along with flagrant repression rather than finding a compromise.

Ochieng knew it was news coverage rather than commentary that had the most influence on readers and leaders. Ironically, it was Ochieng the commentator in the late 1960s who had a huge impact on the many “nationalists” that were trying to make sense of the altogether unexpected direction the country was taking.

Something greater

No local journalist who has not been the editor of an independent daily paper was more consequential than Ochieng in determining Kenya’s media landscape and freedom. He did have a brief stint as Nation Managing Editor in 1988. This is not a sentimental assessment to flatter a departed friend. Numerous others have written about Ochieng’s pioneering breakthroughs, including being the country’s first African sub-editor in 1970.

But in 1968, he had already achieved something greater, becoming the country’s first substantive regular opinion columnist.

Technically, Hillary Ng’weno was the first, as he had a few months earlier been given a column called “Commentary” but he left the Nation soon thereafter for Harvard. Boaz Omori, the Editor, asked Ochieng to take over the column. And what a column it was!

By 1970, Ochieng’s fame had crossed borders. He was asked to take a senior editor’s post at the Daily News in Dar es Salaam by Frene Ginwala. Later, Ochieng served under Benjamin Mkapa, the future president. In 1982 Ochieng was invited to be the Sunday Times Editor in Kampala, but that was short lived as Uganda was in turmoil. The magnitude of these accomplishments reflects how Ochieng bestrode like a colossus over the East African media scene.

To honour Ochieng thus does not mean we gloss over what many condemned as his controversial tenure as Editor-in-Chief of Kanu-owned Kenya Times from 1988-1991, where he argued powerfully for one-party rule.

I am not one who believes we should all think alike on any vital issue, but single party rule under Mwalimu Julius Nyerere in Tanzania or Kenneth Kaunda in Zambia might have been fine. Both men kept their nations united and peaceful. Rational debate and disagreement is at the heart of democracy and a free press.

No person had a more profound impact on my life than Ochieng did – and this was long before I met him. When I returned home from the US to teach at the University of Nairobi in 1968, I was stunned by the power of Ochieng’s columns. While in the US, I had seen how the media was servile in reporting and commenting on the vastly destructive war their government was waging on Vietnam. That was despite the west’s proclamation of media independence.

However, Ochieng was blazing trails in Kenya. Wielding language like a surgical scalpel, and with his unmatched journalistic and political fluency, he was dissecting the fundamental missteps of the new leadership and the newly grasping elites.

He introduced thousands to the potential that journalism held for building a nation.

I soon realised that my goal in wanting to teach – to bring about change in people’s thinking – could be more quickly realised through the media. I ended up as Editor of the Sunday Post. After I was forced to resign, started Viva magazine until, like many others, I had to flee in 1982.

Exceptional integrity

Ochieng has left behind a profound, unmatched legacy with his extraordinary journalistic skills and integrity. But Ochieng was not alone. There were many who fell foul of the “law” and suffered. Despite this enviable record and mastery, Ochieng’s exceptional integrity as well as his restlessness and frequent job moves eventually led him to difficulties at the tail end of his life. He never took advantage of his many senior positions – including while working for President Moi at the Kenya Times – to get a decent plot and build a house in Nairobi, or to accumulate significant wealth for his last years.

How different it is now for senior journalists, who are paid infinitely better than Ochieng and others were. It’s entirely possible that such monetary comfort makes journalists operate within professional and political bubbles, in which journalism’s primary raison d’etre might be forgotten – to scrutinise power and make sure it is not riding roughshod over ordinary folk who have no way of protecting themselves.

Thankfully, once Ochieng reached a point he could not hold a full-time position, Wangethi Mwangi – the Editorial Director at the Nation – recognised his lengthy service with contract that gave Ochieng a decent income.

Decent rental property

Mwangi’s successors continued that practice through to Mr Mathiu now. But once Ochieng was ailing and could not write or edit, the Nation could not continue paying him, though individual journalist friends still supported him.

Ochieng had been happily living on a decent rental property in Kikuyu, but financial pressures forced him to Ongata Rongai, which was hard for him.

Ochieng was an astonishingly learned person: no one I have known in my half century of national and international work was more learned than Ochieng. For this article, I talked to Jerome Corsi, a conservative publisher who once had Ochieng do a research consultancy.

He was aware of Ochieng’s political leanings, but said: “I was astounded about his capacities and knowledge not just of Kenya and Africa but of Europe and the world. It was a rare pleasure to speak to someone so learned and beautifully spoken.”

To honour Ochieng, it is vital journalists look critically at their current operations through the lens of his legacy. We do now enjoy much greater media freedoms, except occasionally during periods of high tension, such as the disputed 2017 election. Are we taking full advantage of such freedoms?

Or is there more freedom now because media has learnt where it can safely push, and where it should not intrude?

The writer is a former Spokesperson for the United Nations and Orange Democratic Movement leader Raila Odinga