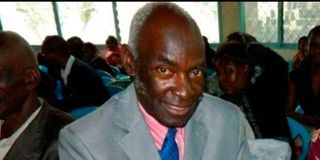

In treasured memory of Mzee Richard Ambani, master of the catalogues and indexes

The late Richard Ambani, the celebrated Kenyan archivist.

Richard Akhonya Ambani, archivist and champion of researchers and students of Kenya's history, died on July 5, 2021. In a career that spanned 56 years, he worked with generations of scholars – both East African and foreign – as they conducted their document searches at the Kenya National Archives.

Mzee Ambani began his career in 1964 at the archives’ previous home: what is now Jogoo House ‘A’.

As a young clerk, he participated in the transfer of the document depository to its present home on Nairobi’s Moi Avenue. He continued to work in its search room long past his retirement as a research officer in 1998. His service only ended in March 2020 when the Covid-19 pandemic closed the institution’s doors.

A master of the catalogues and indexes that mapped the over-stretched system at the archives, Mzee Ambani had an inimitable capacity to trace hard-to-find documents. His modesty of stature and his generosity with his time belied his significance to information flows at the archives.

Cartography

His lengthy service gave him a deep understanding of the system's infrastructure and its choke points. Using a technique that matched the landscape of the archives with a mastery of the cartography of the outside world it referenced, he was able to guide researchers to the necessary resources. That’s why he is laurelled in the acknowledgment pages that preface nearly every significant work of hisotircal scholarship about Kenya.

Even as his brisk pace slowed and his eyesight dimmed, he continued to offer himself to scholars navigating the archives.

Like many pensioners in our times, he found that he had to rely on the kindness of others to sustain himself in retirement. Many researchers regret that they did not do more for him in the difficult last year of his life.

In his childhood, the overnight train from Kisumu brought Richard to Nairobi for the school holidays. He remembered the community spirit that kept Kaloleni’s garden city green and clean when his father rented a house there. His father worked as a foreman at the mills of the Unga Group. Lamenting present ethnic clustering and its effect on work places, he told of an encounter with a stranger celebrating the memory of his father, a strict but fair man who hired people from across the colony without ethnic bias.

When I last sat with Mzee Ambani in 2019, at least three other custodians of the state’s documentary records were close to their retirement. Although the institution had trained scores of interns over the years, a limited grant and a hiring freeze had kept the workforce old, lean and narrow.

Large state investment in a national museum, national library and a new heroes’ park may portend a future of renewal for publicly funded heritage institutions.

However, the nature of these public investments implies a prioritisation of one-off investment in buildings over sustained funding for the technology and labour on which heritage work relies.

Although several modernisation projects had been initiated at the archives, orphaned technologies, unsustainable hardware dependencies, and stalled implementation due to funding shortfalls delayed advancement from the techniques that Ambani had been trained into in the 1960s.

A revitalised practice of archiving would build on the foundations laid by Ambani and others over the last century. In addition to improving the physical infrastructure of conservation and storage, digital extensions would ease public access into the vaults of memory and promote more popular participation in analysing and constructing history.

Document preservation

Successfully digitised public archives such as those built by the BookBunk and DigitalAfricanHeritage projects are portents of a future in which the kind of expertise Ambani accumulated is supplementary, rather than central, to the practice of document preservation and retrieval.

Over shared meals and discussions, Mzee Ambani was a patient teacher. He also had a deep knowledge of the capital and would take researchers on tours of the historical districts of Eastlands; the Kaloleni of his childhood, the old Pumwani houses he had once called home and the Gikomba market.

But like document pages at the archives, this was sepia-tinted history, fading in a rapidly changing country. Those historical neighbourhoods and the communities that had made them home are threatened by redevelopment projects. In June 2020, Mzee Ambani lost all his possessions when his Gikomba apartment block was overwhelmed by a great fire. This included a curated personal archive consisting of sheafs of handwritten notes and a collection of photographs.

Having built his entire adult life around the labour of memory, that loss and displacement disoriented Mzee Ambani and led to the deterioration of his physical and mental health. To better care for him and shield him from the pandemic, his family repatriated him to the land of his birth.

Never a great man, a boss, or a priest, he did not accumulate material wealth, nor achieve personal glory. He did not accumulate prestige either, and was uneducated in ways that earn credentials. Yet his life of work is exemplary expressly for the contribution it made to the success of others, and to the wider project of public remembrance.

The pandemic’s extended ceremony of mourning has taught us the term ‘key worker’. This title clarifies the sustaining labour on which social life and the economy is rooted. In death, it marks losses of life that are deeply consequential even when such workers were unrewarded under present economic configurations.

If history is an accounting process, the terrain on which we settle the question of what biographies are worthy of commemoration, Mzee Ambani’s life of work deserves entry into the chronicles of East African public history.

The Ambani family requests that his old friends send over printed copies of book projects that their grandfather helped realise. They imagine a little library that generations in Ebushingo, Ebulwani may have access to. In his honour, it would also be a fitting tribute to name the street that goes by the archives “Richard Ambani Road”.