South African President Cyril Ramaphosa looks on as he addresses new members of the African National Congress (ANC) during an election campaign ahead of the 2024 general elections, at the Nelson Mandela Community Youth Centre in Chatsworth township, north of Durban, on May 14, 2023.

The bodies of Nelson Mandela and other fallen heroes did not rise from their graves in outrage, as one ‘traditional healer’ had prophesied would happen, if the ‘party of Mandela’ failed at the hustings. But there was little ‘relief’ in the ranks of South Africa’s former sole ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC), that that gruesome manifestation of ‘cosmic unhappiness’ was avoided.

There was nevertheless a good deal of actual and metaphorical wailing and hand-wringing among loyalists of the ‘the oldest liberation movement in Africa’ as results trickled in, showing that the ANC’s ‘liberation dividend’ at the voting both had had its day.

No longer are there hordes among whom loyalty to the ANC may be relied upon, regardless of how poorly or corruptly it governs. That the season of easy wins for the ANC has passed, already widely sensed as being well over, was confirmed when South Africans voted in their droves – some 16.25 million votes cast – with the majority choosing another party to represent their hopes and dreams, nationally and in the regions where they live.

A mass stay-away, which had also been predicted as possible by some analysts and pollsters, did not eventuate, the turnout heading for about 58 per cent.

Instead, there was a relatively strong turnout that told the story of a country making a major change in direction, but perhaps ‘cautiously’ so. For the ANC, post-voting, the future is not merely limited by the low-40s range of support that it now ‘enjoys’ nationally, but also by the practicalities of arriving at working and stable coalitions, first nationally, and then in at least two major provinces, KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng (greater Johannesburg and Pretoria).

Ruling coalition

Since 2021, South Africans have become used to coalitions running major metros, usually poorly, and almost all within a highly unstable context where the ruling coalition could change at any time.

Accordingly, pre-poll inputs from voters were that they were not widely supportive of coalitions, but would accept them – in return for better governance and less corruption. The ANC’s much-desired 50-per cent-plus outcome gone, the former sole ruling party must now work out with which parties it can functionally operate. Even as the votes were still being counted, former President Jacob Zuma and his mainly Zulu supporters were among those ‘delighted’ with the results of the seventh post-apartheid election, scoring in the low double-digits at around 11 percent.

Zuma and uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK, or ‘Spear of the Nation’) are now set to be major players in at least two provinces, one the Zulu homeland where it has dominated, the other the country’s administrative and industrial heartland.

With over 40 per cent of the vote in KwaZulu-Natal, over twice the ANC’s support there, the Zulu homeland is now Zuma’s turf.

In Gauteng, the ANC has a real headache, having earned just a third of the votes, and needing to partner with both the EFF and MK to rule there – the latter mix not on the cards at present. Most likely an arrangement with the weakened EFF will be required. But even so, another two or maybe three parties will be needed for such a coalition to break through the 50 per cent level. The Democratic Alliance (DA), running a close second to the ANC in greater Johannesburg and Pretoria, has even less chance of forming a working alliance in Gauteng.

Upheavals in the governance of Gauteng, the most important province politically and economically, as well as the most populated, may therefore be likely. Though MK may be happy with effectively controlling KwaZulu-Natal, and being potential ‘kingmakers’ elsewhere, there are no signs that Zuma and his loyalists are yet prepared to work with the ANC under its current leader, President Cyril Ramaphosa. There would be no cooperation with the ANC, Zuma has declared, until Ramaphosa is out of the picture.

Of the major parties, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), which also suffered loss of support to Zuma’s yet-more-radical MK, may be ‘easiest’ for the ANC to work with nationally, and in regions where that combination may help achieve a majority. But these are precisely the same ‘troubled partnerships’ which have marked some of the chaos and turbulence that have plagued multi-party control of urban centres like Johannesburg and Pretoria (Tshwane).

Free and fair

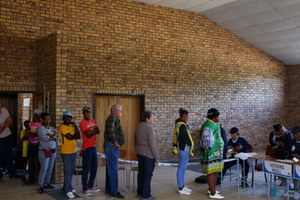

With international observers, plus local entities such as the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), declaring the election substantively free and fair, most relatively minor issues – such as late polling station openings and slow vote-capturing causing long queues, plus numerous technical hitches with digital vote capturing – all being assessed as ‘not vital’ to the outcome, the ANC has now to “buckle down and get to work”, as one senior party source said privately. Technical problems aside, however, the election was generally well-received due to the very few incidents of alleged or actual misconduct, and applauded as an exemplar of ‘democracy in action’ in Africa.

The vast number of new parties, some with a core of just a few members, some literally one-man shows, did not receive the support which had expected to be more widely spread due to the high levels of electorate disenchantment with established parties. Instead, the disgruntled have either given the ANC another chance – hence ANC support did not fall to sub-40 per cent, as some earlier polls had indicated was possible – or have opted for Zuma and his MK, as a radical alternative.

The EFF has not leapt into second place, as it hoped, to be the ‘future ruling party in waiting’, which is how Julius Melema and his fellow Marxist-Leninist comrades had played their position pre-election, but rather has fallen back. Ground lost by the EFF was won by MK, which has ‘come from nowhere’ in December to be now the third largest party, ahead of Malema’s Red Berets. The official opposition Democratic Alliance (DA) has re-cemented itself in that role by achieving support in the low-20 percentiles, after showing some weakness in the 2021 local government elections. The rest are sharing just a few percentage points between them.

This election demonstrated a broader trend already evident in the last 20 years – most South Africans are, in their own terms, ‘conservative’ politically, preferring those they know to newcomers, and centrists over radicals.

As such, this election will give heart to those looking to South Africa as an example of a maturing post-colonial democratic society, in which the ‘party of liberation’ has worn out its free pass to continue leading without consequence, and where wildly contesting views may be expected to be reliably weighed at the voting booth by an increasingly sophisticated electorate.