The good, bad and ugly side of Qatar as World Cup set for kick-off

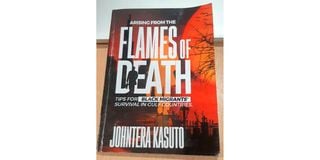

The book cover of Flames of Death by Johntera Kasoto.

What you need to know:

- Country has been accused of disregarding human rights violations ahead of Fifa event

- A Kenyan, who worked in the Asian nation for four years, details, in his book, the treatment of immigrants, especially blacks

Reports of disregard for immigrant workers’ rights in Qatar may be like just another sad story to many Kenyans, but not for Johntera Kasuto who lived and worked in the country for four years.

Mr Kasuto, 34, wrote a book in which he terms the treatment of immigrants in the Asian country, especially blacks, modern slavery.

The book, titled Arising from the Flames of Death: Tips for Black Migrants’ Survival in Gulf Countries, was released in 2020. In it, Mr Kasuto details some of the things he saw, heard and experienced when he worked in Qatar.

He left Kenya in September 2016—quitting his job as a supermarket employee in Eldoret—to become a sales executive in Qatar. Mr Kasuto, who hails from Kitale, Trans Nzoia County, returned home in September 2020 at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Whereas he has a few things to praise Qatar for, among them the magnificent skyscrapers, tax-free regime for businesses, strong religious foundations and a culture of punctuality, the book details the many ways employers mistreat employees and how the general population looks down upon blacks.

His passport was confiscated on the first day he landed in Doha. Usage of his mobile phone was limited, and he was once punished for appearing too close to another immigrant female worker at a church event.

Moreover, he notes that some jobs demand that a black person works while standing the entire day—and that may mean more than 12 hours a shift—and that the racism is appalling.

“The sneers and snubs as you pass by these [locals] are evident. Some of them press their noses tight when you pass by as if you were a foul-smelling donkey. It’s quite sickening and dehumanising. The black-skinned are unfairly regarded as dirty and hence quite ‘stinky’. Unfortunately, it is one of the social hazards one has to live with in an environment of very scanty friends,” he writes.

As far as labour issues are concerned, he says immigrant workers are denied harsh weather safeguards, subjected to arbitrary pay cuts, have restrictions on movement, communication and socialisation, and are hardly promoted. Female domestic workers, he notes, are subjected to sexual abuse that sometimes takes

the form of gang rape. They are also sometimes denied food.

“Black African females greatly suffer sexual harassment. While they do not enjoy the privilege of earning the equivalence of their Arab counterparts [mostly those who emigrate from northern African countries], should their promotion be considered remotely as an issue on the employer’s or supervisor’s cards, then it can only be through the avenue of sexual gratification,” he writes.

“The paradox to this is that if a black African male makes the unforgivable sin of attempting to talk to any of their ladies, the punishment is swift and brutal. Those very men who sexually abuse the African migrant workers are the same ones who overly protect their own by making sure you spend time in jail. Talk of double standards,” he adds.

Dehumanising conditions

He also narrates an incident where he was photographed sitting next to a Filipino woman at a church event. The photo was later posted on social media and was interpreted to mean that he was getting too comfortable.

The result was a transfer to a distant place “under very dehumanising conditions on construction sites like someone who had never seen the inside of a classroom and at a drastically reduced pay”.

He advises black workers who may be planning to work in the Gulf to note the unwritten rule that black men should not look Arab women in the face when they are talking, and that they should keep a “respectable” distance from them.

Qatar, a tiny country in western Asia, is hosting this year’s World Cup. Its disinterest amid complaints about human rights abuses against workers is one of the grounds some critics have been raising while arguing that it did not deserve to host a tournament of such magnitude.

The country sits on 11,581 square kilometres, compared to Kenya’s 580,367. That means 50 Qatars can fit inside Kenya. It is endowed with some of the largest petroleum and natural gas deposits in the world.

Because of its oil wealth, its citizens enjoy a high standard of living and a well-established system of social services. A majority of the population, as per a 2015 count, are non-locals. Native Qataris only account for 11.6 per cent of the population. Regardless, 40 per cent of its population is made of Arabs and 99.1 percent of residents live in urban areas.

Qatar’s riches make it an attractive destination for many Kenyans in search of better-earning careers, and Mr Kasuto admits that he was drawn there by the dream of striking it rich.

“It was with bated breath that I waited for the big day of departure,” he writes.

However, in his book, he expresses bitterness, saying most of the depiction of riches is a façade. He also criticises the cultural set-up of the people there. “It is no secret that some TV programmes denoting blacks and underdogs befitting slave treatment dot the screens in the Gulf region.”

In hotels, he says, black people have to pay before they get meals while the rest are served while seated. Blacks are also not allowed to visit some places in malls. He remembers being chased away from a section for female garments during one outing.

Nearly 70 per cent of the Qatari population is Muslim, and some of their practices stem from Islamic teachings. For instance, Mr Kasuto writes, alcohol should never be taken in public, discos are deliberately overpriced to lock out majority of the populace, and nothing is handed to someone using the left hand.

“Never, even in your wildest dreams, present something to the Arabs using your left hand, however good-intentioned you are,” he writes, adding you should also avoid handshakes unless the other person initiates it.

Also, during Ramadhan, one should not be seen in public drinking water. “Doing so could easily be interpreted as sacrilege,” he writes. “If you have to drink this much-needed water due to the burning heat, go into seclusion and privately, while beyond the glare of piercing eyes, quench your thirst.”

In the latter chapters of the book, Mr Kasuto says he has forgiven all who wronged him and shares ways in which someone can thrive while working in the Gulf. He also shares scriptures that can encourage those hurt by the working conditions and social segregation.

And though he does not expressly discourage anyone from going to Qatar for work, Mr Kasuto observes that whoever wants to head to the Gulf needs to get a true picture of the realities on the ground before making the decision. The book, which Mr Kasuto wrote over two years, costs Sh1,000 and is available at the Nuria Online Shop.