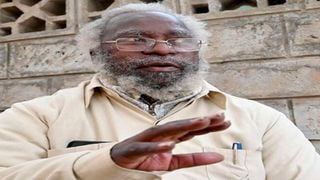

Prof Esaiah Ngotho Kariuki.

| Sila Kiplagat | Nation Media GroupPolitics

Premium

The mysterious driver in Mutugi’s Bar arrest after Saba Saba protests

Thirty-one years ago, on July 11, 1990, just four days after the Kamukunji Saba Saba protests, police officers silently surrounded Mutugi’s Bar in Dagoretti Corner, Nairobi, at midnight.

On the fourth floor of the bar were four men who had gathered for drinks and political talk on the protest earlier that week.

Among them were Prof Esaiah Ngotho Kariuki, George Anyona (now deceased), Njeru Kathangu and Edward Okong’o Oyugi. On the ground floor, James Maina, who was Ngotho’s driver and political mentee, downed his two bottles of Guinness beside his friend, Gichana.

While the four at the top floor discussed coffee and tea farming and other pressing issues in the country, two officers in black suits were making their way into the hotel. One of them, recalls Maina, had a walkie-talkie, and when he tried to question them, they rebuffed him and proceeded up the stairs.

“When they came in, they went straight to the lavatories, and I could sense something was amiss. I left to warn the others, but on the first floor, they caught up with me and ordered me to go back down. When I saw the walkie-talkie, I realised they were police officers and not ordinary clients,” recalls Maina.

Police vehicles

He went back down, alerted Gichana and walked out, only to find vehicles belonging to the four men blocked by two police vehicles each. The police vehicles had private number plates.

“They had only left about a foot distance (between the cars) and I realised I could not get my car out. I did not go back to get my drinks or belongings, I simply walked away very slowly. Two men followed me for some distance, but eventually gave up, probably thinking I was a drunkard,” says Maina.

While his friends were being arrested and being forced into their vehicles, Maina walked cautiously, following a route that would get him to the main road where he could see Mutugi’s Bar. Standing on higher ground, he realised that the whole area was surrounded by police officers.

He entered another bar frequented by university students to wait out the drama that was about to play out. A few hours later, he went to his view point, and realised his colleagues’ vehicles were missing, and only his remained at the parking.

Pretended to be a passer-by

“The police officers had forced my colleagues into their own vehicles, then took position at the wheel. I decided to go back and get my car, but found two police officers sitting beside it waiting for me. I pretended I was just a passer-by. The next day, when I went to Ngotho’s house to find out what had happened, I was warned to leave, because apparently, the police were looking for me,” explains Maina.

The night before, on realising that he had escaped, police officers went around the lodging rooms, waking up the occupants, beating them up and asking them to reveal their identities.

“They not only did that at Mutugi’s Bar, they went around other lodgings in the area. My vehicle was towed to the CID headquarters, and Ngotho’s wife had to retrieve it,” Maina says.

“My friend Gichana, who refused to leave with me, was caught the next morning and kept in Kamiti Maximum Prison for six months on accusations that he was a spy. He was later released without any charges,” he adds.

Not cowardice

He says that his act of escaping was not an act of cowardice.

“Have you ever seen an antelope waiting for a leopard? Times were tough then, and even speaking to a journalist was a hard task. You were always suspicious that he/she was an undercover agent,” says Maina.

Talking about the protest, he says the group had only gone there to demand democracy for the country. He was only 31.

“We did not go there to fight. We wanted multi-party democracy. We went there to demand democracy that would eradicate people’s fear and suspicion of each other, but we were met with war. We were beaten, and many people were killed including one of my friends. The search for democracy has been a long journey,” he explains, adding that his friend and political mentor, Prof Ngotho Kariuki paid a heavier price.

Prof Ngotho Kariuki, lecturer who was detained twice

On the other end, Prof Ngotho Kariuki does not regret anything he did. He was detained twice, and was tortured alongside Mr Raila Odinga at the Nyayo torture chambers.

On the day of the protest, he and his friend Kariuki Gatito (now deceased) had organised a football match despite the fact that the day had already been declared illegal. With other friends, they disguised themselves and moved to Mathare to mobilise other people. When they got back, they found the police already chasing people out of the grounds. That evening, they slept in a lodging on River Road, fearing that if they went home, they would be arrested.

On the day of the arrest, the four had met at Club Kutwa in Madaraka. From there, they each took their vehicles to Mutugi’s Bar.

Discussing politics

“At Mutugi’s, we were discussing politics and the problems that farmers were facing and I had written them down on a piece of paper, which was later used in court as evidence that we had taken minutes,” says the professor.

After the midnight arrest, he explains that they were ferried around by police officers and were only taken to their homes a day later.

“They would leave us in the car guarded and go harass our wives and children, questioning them about our whereabouts. My children were young then, and they said they didn’t know where I was,” explains Ngotho.

Taken to Nyayo House

After that, they were taken to the Nyayo House torture chambers. When the trial started, he was sentenced to 49 years in prison, but following public outcry, he only spent three years in prison. He was then a consultant working with the East and Southern African Management Institute, working with the World Bank.

“I have documented the manner of torture at Nyayo house in my book titled Two Weeks in Hell. We were naked, on a cold wet floor, and then they could pick you up and take you to a higher floor where you were beaten then taken back to the cell,” adds Ngotho, as his eyes get teary.

“It was brutal, but later, the government disowned the Nyayo House torture chambers even though we wanted it declared as a monument of shame. Even today, we still struggle to memorialise it as a museum,” he adds.

Not bitter

He explains that he is not bitter as that was a mission he had chosen. He adds that his wounds from the torture have healed, and that he has forgiven those who were responsible.

“We must learn to move on. If you don’t forgive, then you carry the burden. Multiparty came and now we are enjoying its fruits. I carry no grudge, and I never asked for compensation. What would annoy me is to see the young generation taken back to the same,” he says. “Nothing comes for free, and the young generation must speak out. They have a duty to reclaim their country,” explains the professor.

He laughs, explaining that at the time, he had already served his first detention from 1985 to 1989.

“It was dubbed Mwakenya. We had been arrested because we had organised a movement to try and overthrow the system. We were detained in Manyani, a place that was infested with wild animals, so you wouldn’t dare escape. After we came out, we still did not feel like we had done it all. People thought we were foolish. They would ask us, ‘you people were in detention the other day, aren’t you scared of going back?’ but we persisted,” says Ngotho, 72.

Saba Saba protests

Eventually, the Saba Saba protests happened, and they went to prison for three years, and were released in 1993 on bail pending appeal. After that, he and his family left the country, and he taught in Zimbabwe, Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Cameroon and the United Kingdom.

“I came back in 2011 because I had missed home. But I am proud of how far we have come in matters freedom of speech. People can now talk about the President freely without fear. They even make memes about him and he laughs at them. That was unheard of in the past. This is a big achievement on its own. It may not be the best, but it is okay. What remains is for the other generations, I can now rest,” he concludes.