Demonstrators along Moi Avenue during the Saba Saba demonstrations in Nairobi, July 7, 2011.

| File | Nation Media GroupPolitics

Premium

31 years after defining Saba Saba rally, democracy still a work in progress

Exactly 31 years ago on a day like this, a series of events at the Kamukunji grounds in Nairobi left 39 dead, scores injured, 5,000 arrested and at least 1,000 subsequently charged with rioting and looting.

The day has come to be known as Saba Saba, a Swahili word for “Seven Seven”, to represent the seventh day of the seventh month that the nationwide anti-dictatorship riots began in July 1990.

Anti-riot police clear Nairobi streets during Saba Saba demonstrations in 1990 at the height of the quest for multi-party democracy. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

The protests lasted four days. Three of the seven architects of the chaos were arrested. They were Charles Rubia, Kenneth Matiba and Raila Odinga.

The other organisers included Prof Ngotho wa Kariuki, Prof Edward Oyugi, George Anyona and Mtumishi Njeru Kathangu. They are all alive, except Rubia, Anyona and Matiba.

Those arrested were subjected to direct detention without trial. Their antics were enough to dislodge the slight calm that President Daniel Toroitich arap Moi had managed to gather after stifling an attempted putsch orchestrated by the army man Hezekiah Ochuka eight years earlier.

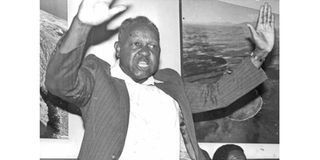

Kenneth Matiba at a past Saba Saba rally.

With his nerves frazzled by the botched coup, the President abolished multiparty politics and strengthened the ruling party Kanu, which he used to rule the nation with an iron fist for 24 years, before being toppled by the tsunami duo of Mwai Kibaki and Raila Odinga in 2002 in a humiliating defeat.

Kenyans, angered by how the government was running its affairs through repression and oppression, were more than ready to separate body from soul as they defiantly assembled at the Kamukuji Grounds.

Like revered freedom fighter Dedan Kimathi, they opted to “die on their legs than live on their knees begging for scraps” from the high-handed dictator. They were tired of endemic corruption, nepotism, forceful crushing of dissent, police brutality and many other vices that threatened to reduce Kenya to a banana republic.

The late Martin Shikuku, Siaya Senator James Orengo and other Young Turks during the Saba Saba protests in early 90s.

Five months before the angst-charged Kenyans assembled at Kamukunji to voice their protestations, Robert Ouko, a Cabinet minister in President Moi’s government was murdered not far from his home in Koru and his tortured body found at Got Alila Hills.

The foul assassination of the beloved statesman served as fuel to the fire already sparked in desperate Kenyans. It was highly suspected that the sharp-witted minister was killed by close operatives of Mr Moi. His death is still a mystery 31 years later.

Though the majority wanted the tough President out, organising the Saba Saba rally had not been an easy task. Secretly, leaflets were published and distributed across the country through proxies of the organisers, mostly matatu touts and soccer teams. The strategy worked, and thousands thronged the venue on the D-day.

Suspecting that the rally was another attempt to edge him out of power, the President declared the Kamukunji meeting illegal. Contingents of armed police officers were sent to the meeting venue.

Unlike in the past, when they fled in fear as police appeared, citizens, emboldened by their desire to bring change and their suffering under one-party rule, stayed put.

Violence erupted. Live bullets were sprayed on the defenseless protesters who were singularly armed by their ideologies of a democratic country and placards stating so.

When push came to a shove, they disbanded their pretty analogies of gaining peace through soft nudges and turned to stones. They retaliated like never before - stones, wood and whatever could be carried was used to fight the police.

Property worth millions were destroyed in the highly charged melee. The law enforcement officers worked on strict orders to quench a relentless inferno that burnt from the pit of the hearts of the tired plebiscites who had nothing to lose but everything to gain.

Anti riot police along Moi Avenue during the Saba Saba demonstrations in Nairobi, July 7, 2011.

Kenyans were angered by the toothless Judiciary that had been filled by judges and magistrates cherry-picked by the President. They were agitating for a stronger Parliament that had by then been reduced to a shell with MPs nothing but followers of the Head of State.

“It was about reclaiming our country and reinstating back to the ideal vistas that the freedom fighters had envisaged when they gave their lives in the struggle for independence,” Mr Kathangu, or Mtumishi, one of the organisers of the unforgettable rally 31 years ago, told the Nation.

“We wanted the economy revitalised, we wanted an Executive filled with competent people who had a backbone to refuse doing what the President wanted every time. It was about change.”

It was a bloody day, fused with smoke, punctuated with shrieks of pain, filled with sweat, chants of hope, and relentless running.

Saba Saba was the first major protest for democracy to allow the people to have a voice in how the country would be governed. It was the slight nudge that the populace needed to wrest themselves from permanent subservience and to do away with the muzzle they had been forced to wear for so long.

It was a day to call for the end of the hostility witnessed when the State rained blows on the opposition.

Sixteen months later, following more protests and agitations - which also involved second-tier revolution leaders such as James Orengo and the late Martin Shikuku - for change saw President Moi grudgingly agree to the repeal of Section 2A of the Constitution and multiparty politics was ushered back.

A record 19 political parties were registered. Despite these changes, the sharp-eyed man from Sacho went on to rule for two more terms after winning dismally in the 1992 and 1997 elections.

This was after pouring all resources that the State could afford into different sub-sections of Kanu, including Young Kenya 1992 (YK-1992), led by former Lugari MP Cyrus Jirongo and the current Deputy President Wiliam Ruto, then 25.

The main opposition party, the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (Ford), was split through the efforts of State operatives who were also behind the registration of the numerous but weak political parties.

President Moi was accused of allowing the creation of the numerous outfits with the sole purpose of using them to fuel ethnic antagonism.

Whereas democracy appears to have progressed over the years since Saba Saba, police brutality, rampant corruption, a worried Judiciary struggling for its independence, a backboneless Parliament still best describe Kenya.

Mtumishi Kathangu has expressed his exasperation at the current state of affairs, saying it was perhaps time for another Saba Saba rally to bring this nation to order.

“We have backpedalled to the same point we were in 1990. The economy has collapsed. We are constantly begging for loans to pull through. Kenya is down in the gutter,” he said.

“Our courts are struggling daily to be independent, the Parliament is voiceless and the Executive is a spectator of the happenings in the country. It is time we push to reclaim our country just like in 1990.”