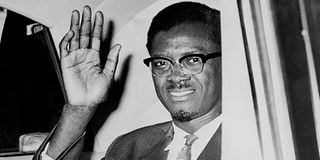

Africa remembers Lumumba, bright spark in a land of despair

Lumumba was the statesman and politician, the first prime minister of the Republic of Congo.

What you need to know:

- The assassination of Congo’s wildly popular Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba by CIA and Belgian agents half-a-century ago paved the way for the country’s economic exploitation and sowed the seeds of corruption and state failure that have plagued the resource-rich country for decades

The town in which I grew up has three important marks in his memory: A dispensary, a road and a housing estate named after Patrice Lumumba.

In addition to that, there are friends and acquaintances named Patrick Lumumba, the first name being an English rendition of the Patrice.

I believe these tributes to Lumumba are not only true to Kenya. My guess is that there are streets, buildings and children named after Lumumba all over Africa.

Fifty years after his death, one must ask who is Patrice Lumumba and why is he remembered so? What did his death mean for his country Congo and for the whole of Africa? John Henrik Clarke, then the United Nations correspondent on African affairs described Lumumba in these words shortly after his death: No other personality in African history has leaped so suddenly from death to martyrdom.

He added that Lumumba had in his death already made a greater contribution to the liberation and understanding of Africa than he could have if he had lived longer. He concluded with interesting prescience that strikes even those of us born decades after Lumumba’s death that Lumumba’s death cast forth a spirit that would roam Africa for many years to come.

Patrice Emery Lumumba was the first, also probably the only, democratically elected Prime Minister of the Congo and led it to independence. However, looking at it by African standards Lumumba must be distinguished among African independence leaders in a radical way. He was about 35 years old when he became Prime Minister of Congo in contrast to the average African leader at independence who was probably sexagenerian at independence.

Secondly, Lumumba was officially Prime Minister of the Congo for only 67 days in a continent where leaders count their tenure in decades. Born in 1925 at a place known as Onalua in Kasai Province in the Congo (then a colony of Belgium), Lumumba attended a missionary school and thereafter went to work in Kindu-Port-Empain.

He moved to Kinshasa (then known as Leopoldville) where he worked for a period as a postal clerk. In 1955, Lumumba joined and became the regional president of a trade union for civil servants in the Congo. This trade union was unique for the fact that unlike others in the Congo at the time, it was not affiliated to the Socialist or Roman Catholic trade union federations.

At around the same period that Lumumba became involved with trade unionism, he joined a political party known as the Belgian Liberal party.

This is where Lumumba embarked on his flight path to the leadership of his country towards independence. However, shortly, thereafter Lumumba would go to jail on charges of embezzlement from the post office. He was sentenced to imprisonment for about one year and a fine.

Lumumba left prison and in 1958 formed the “Mouvement National Congolais” (The Congolese National Movement-CNM). This party was intended to be the first nation-wide party in the Congo and eschewed the regionalism and ethnic mobilisation for which political parties in the Congo were previously based upon.

It was while leading this party that Lumumba got to attend the first All Africa People’s Conference at the invitation of Dr Kwame Nkrumah. It is said that the attendance at this conference and the people he met at it changed or otherwise transformed Lumumba into a more militant pan-Africanist.

Lumumba began to think that the Congo needed to follow the path of Ghana towards independence and with some urgency. The Belgians saw it differently: In 1959 it announced a programme starting with local elections in the Congo that same year but intended to lead towards independence after at least five years. Lumumba and his party’s initial opposition to what they considered a delaying tactic on the part of the Belgian colonial authorities led to his being imprisoned for incitement of a riot after deaths in Stanleyville during the protests.

However, the MNC later decided to contest the elections and won a huge victory in Stanleyville while Lumumba was still in jail. At the MNC’s insistence that it would not participate at the conference convened in Belgium to discuss the future of the Congo, Lumumba was released from prison to attend this conference as MNC’s delegate.

The Belgian government and the various parties representing the people of the Congo agreed to hold elections in May, 1960, before independence would be formally granted in June of the same year. The MNC won these elections resoundingly and Lumumba was appointed Prime Minister while Joseph Kasavubu of the Alliance de Bakongo party was elected president.

Although there were several parties which participated in this election, Lumumba and his MNC were unique in the sense that he was the only leader in the Congo with anything like a national following at this time.

Lumumba’s problems and those of the Congo began right on the day of independence. He was even excluded from the official programme on independence day. Instead King Baudouin and Kasavubu were the ones to speak. The king spoke to the effect that it was now up to the people of the Congo to justify the confidence that Belgium had shown in them by granting independence. These and other words angered Lumumba.

It is often said that few African leaders at independence were prepared for governance of their nations and lacked the requisite tools of statecraft and governance etiquette on the day of independence. Lumumba was no exception in this regard but once again he is in rare company because most independence leaders spoke in measured and reconciliatory terms in their independence day speeches. Not Lumumba. His response to the king on this occasion was very unlike what is otherwise known of him.

His speech, delivered from notes he made during the king’s speech, is famous for its content if not for its tone. To the cheers of the Congolese present, Lumumba said that the king had only sought to glorify what was no more than humiliating slavery that was imposed by force.

He continued in these words: “We have known sarcasm and insults, endured blows morning noon and night… We have seen our lands despoiled under the terms of what was supposedly the law of the land but which only recognised the right of the strongest. We have seen that the law was quite different for a white man than for a black: accommodating for the former, cruel and inhuman for the latter.”

Martin Meredith records in his Book The State of Africa that Lumumba’s response on this day so angered the king and the other Belgian officials that the official lunch after the ceremony was delayed while the Belgians debated whether to boycott it.

Lumumba therefore led the Congo’s first elected government, which was a coalition which consisted of the MNC and about 11 other parties, as a confident if inexperienced Prime-Minister of the Congo ready to meet the challenges of a newly independent nation.

Granted, Lumumba may have been a tad too enthusiastic and possibly mistaken about the future of his country. At independence, the Congo had only 30 university graduates with no Congolese doctors or secondary school teachers. Its largest trained professional cadre were its 600 priests. However, because no other African colony possessed the mineral effusiveness of the Congo generally and Katanga region particularly, in terms of copper, diamonds and uranium, Lumumba’s optimism for the Congo’s future cannot be said to have been completely baseless.

The next 201 days would set the Congo on a path of delirium no one could have foretold. This started with the mutiny of a few units of the armed forces over poor pay and working conditions, although the force had remained under the command and control of the Belgian officer corps. Lumumba sought to replace these officers with Congolese with immediate effect and drew by appointing a few of the junior Congolese officers into the higher ranks previously unavailable to the Congo citizens. One of the first beneficiaries of this promotions was Joseph Mobutu who was then appointed Chief of Staff.

The mutiny did not subside after this but Lumumba declined the offer of the Belgian government to use its troops in the Congo to restore order. The Belgian government unilaterally ordered its troops to action because it still had many citizens in the Congo.

Within this chaos, Moise Tshombe, a leader from Katanga Province declared it a state independent of the rest of the Congo. It is said that Tshombe was assured and bolstered in this declaration of secession by the Belgian government and the other Belgian corporations that had been enjoying mining rights in the region.

Within two weeks of independence, Lumumba’s government had experienced a mutiny and an attempt at secession by sections of the country, politics of a dimension which Lumumba himself was ill-prepared. Lumumba sought the intervention of the United Nations which responded quickly with troops mainly drawn from African countries.

Lumumba was not content with mere peace-keeping role for the United Nations. He wanted the UN force to engage the Belgian troops and get them out of the Congo completely and threatened to invite the Soviet Union for help if the UN did not permit the troops to oust the Belgian army from Congo.

The Belgian armed forces would leave shortly thereafter but the Katanga secession remained a problem. It is this threat by Lumumba to walk in the crevices of the cold war politics that may have doomed his government and himself as a person.

A new front for Lumumba’s battles opened when on 5th September, 1960 (67 days into Congo’s Independence), President Kasavubu dismissed Lumumba as Prime Minister in a move of questionable legal standing. Lumumba rejected this dismissal and himself sought to dismiss the president. The resultant stalemate did not help matters within the government; UN reports have indicated that the Belgians in the Congo civil service impeded the UN civilian experts’ work within the government.

In this stalemate, the Congolese Army under the command of Mobutu, seized power on 14th September, 1960. Lumumba was placed under house arrest while Kasavubu was retained as President. In the meantime, Mobutu, with the support and financial backing of the western powers, ordered that government be run by a “College of Commissioners”, following closure of Parliament. In November of the same year, Kasavubu’s government’s credentials were recognised by the UN although some African countries did not approve of this action. This action effectively neutralised Lumumba.

Lumumba may have made the intentions of his enemies easier to achieve when sometime in November, 1960 he decided to go to Stanleyville where he had his political base. His intention was to set up an alternative government. Lumumba decided to make this journey even though he was aware that the UN troops that were protecting him could not guarantee his security outside his residence in Leopoldville. “If I die, so be it”, he told a friend, adding that the Congo needed martyrs.

On 1st December, Lumumba was captured on the banks of the Sankururu river by Mobutu’s forces before he reached Stanleyville. He appealed unsuccessfully to the UN troops for protection. Amidst serious beatings, he was flown back to Leopoldville and held in an army prison.

On 15th January, 1961 Lumumba and his two colleagues (Okito and Mpolo) was flown to Elizabethville and handed over to Tshombe’s forces in Katanga commanded by Belgian soldiers. After this, what happened to Lumumba was a matter of conjecture until the year 2000 when Lutto De Witte published his book by the Title The Assassination of Lumumba.

On arrival at Elizabethville, Lumumba and two colleagues of his were taken to a house where they were tortured and kept in the bathroom. Tshombe and other ministers in the Katanga secessionist regime were physically present and participated in the torture.

Tshombe’s butler is said to have remarked that his boss was covered in blood when he returned to his residence!

Later that night, Lumumba and his colleagues were driven from this house in a convoy which included Tshombe and other members of the Katanga government and Belgian soldiers to a bush about 50 kilometres out where a grave had been dug in readiness for their elimination. Lumumba asked if they were to be killed and a Belgian soldier responded in the affirmative.

Thereafter Okito, Mpolo and Lumumba were executed in turns by firing squad while standing against a tree. This tree was still riddled with bullets 27 years later. The following night, the bodies were removed from the grave hacked to pieces and thrown into a barrel of sulphuric acid. Whatever was not consumed by the acid such as the bones and teeth were ground and thrown away. The intention was that no trace of Lumumba or his colleagues would be found.

US government documents released within the past 10 years have detailed American involvement in the assassination, including making payments to Kasavubu, Mobutu and other key figures in facilitation fees. There is also strong evidence of collaboration between Belgium and the US.

What then is special about Lumumba, a man who died before his 36th birthday, on the 201st day after independence and having been prime minister for a mere 67 days? John Enrik Clarke gives a hint why. He says that he (Lumumba) proved that legitimacy of a post-colonial regime in Africa relates more to a regime’s credentials as a representative of a genuine nationalism fighting against the intrigues of neo-colonialism.

This is why Lumumba is still extolled as the “Best Son of Africa” and the “Lincoln of the Congo”.

Lumumba’s place of eminence cannot be denied: even Joseph Mobutu once described him as “this illustrious Congolese, this great African”. In his short life and even brief tenure in government office, Patrice Lumumba wrote history that leaves all political opponents (Mobutu, Kasavubu and Tshombe) in his wake.

I am sure it is not only the Congolese who were wondering this week “What if Patrice Lumumba had lived longer?” But he reminds us that it is not the number of days in office or life generally that give it value; it is the value that you give to those days of service.