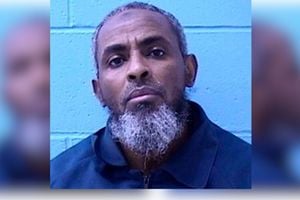

Mr Tom Cholmondeley in a prison van in 2009 after he was released from custody before his term was over because of good conduct.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

‘For Love of Soysambu’: The untold story of Delamere scion Tom Cholmondeley

What you need to know:

- For Love of Soysambu is a treasured addition on how the white settlers’ adopted in the new country and their split identity crisis.

- In the colonial historiography, this book has largely trivialised the human rights abuse that took place in Soysambu.

On the night before Tom Cholmondeley died during a routine hip operation at a Nairobi hospital, a Thai girlfriend – hitherto unknown to the family – sneaked into his hospital room “to spend the evening with him”.

Nobody else seemed to know Amyra or her arrival on that fateful Tuesday, August 16, 2016.

Tom had walked into the city hospital accompanied by his girlfriend, Sally Dudmesh, who lay besides him as they waited for the anaesthetist and as he argued with nurses that he did not require an epidural anaesthesia – an injection around the spinal cord during the scheduled hip surgery.

The hip surgery had been scheduled for Wednesday morning, August 16 and Dudmesh had left him for the night. That is the time Tom’s Thai girlfriend arrived.

“(Tom and Amyra) were planning a future together,” writes Juliet Barnes in the latest book, For Love of Soysambu, which is chronicling the ever-evolving story of the Delameres of Kenya.

If that happened, Dudmesh was going to be unlucky for the third time in a row. A jewellery designer, Dudmesh ’s previous boyfriend Giles Thornton, a wildlife conservationist, had been shot dead while Tonio Trzebinski, the other casanova who was to marry her was again shot.

Before her wedding to Tonio was called off, Sally had flown to London to buy the wedding gown when she was called by German-born fashion designer Anna Cunningham-Reid and told to forget the ceremony. And to make matters worse, it was Anna who was now to marry Tonio.

Cholmondeley's philandering

According to the Telegraph, Anna – who was then married – had met Tonio in Funzi island during a New Year’s eve party. As Anna’s husband lay in bed, after being stung by a scorpion, Tonio and Anna were elsewhere in the bush. Some 11 years later, Tonio – a man I had interviewed three times on his art – was shot dead on October 16, 2001 as he drove to the house of his Nairobi mistress, Natasha Illum Berg.

In the Soysambu circles, both Dudmesh and Tom’s wife, Sally Cholmondeley, knew each other. In such circles, naivety also runs deep. This is what happened: Shortly after Tom had left custody over the murder of Samson ole Sisina, a Kenya Wildlife Service warden, there was talk around Soysambu that the Maasai would file a civil suit and demand compensation. There was also national tension.

“In this febrile climate of feeling (Tom’s wife) Sally felt (he) shouldn’t be on Soysambu. (Again) she was angered by his continued correspondence with an English girlfriend…” Barnes tells us. “So she suggested (her friend) Sally (Dudmesh) take him on Safari in northern Kenya (where they) followed a train of hired camels down the remote Seiya Lugga, accompanied by three Samburu men, who didn’t care who Tom was.”

It was, perhaps, a marital mistake. “At night, he would fall into the arms of Dudmesh,” writes Barnes. But Sally Dudmesh did not want to be a “secret mistress” and as she told Barnes “she wasn’t the type who broke up marriages (and) that (Tom’s) marriage had been over.”

Actually, as Juliet Barnes tells us, it was Dudmesh who broke the news about their love affair after Samburu to Tom’s wife, Sally Cholmondeley,” - a revelation that didn’t go down well.”

But if Dudmesh thought she would be married by Tom, she was wrong.

Unknown to her and as Sally Cholmondeley left, Tom had started dating a Thai woman. The philandering, even before he settled with Dudmesh, took him to Thailand to meet Amyra. Nobody within the family knew where Tom was.

Human rights abuse

“It later turned out that Tom was in Thailand visiting another woman. Soon after arriving (in Thailand),” Barnes reveals, “He’d slipped and fallen from over half way up the steep path besides a ten-tier waterfall. Realising he was unable to move, he was obliged to descend the treacherous slope in a stretcher.”

And that is the injury that would later cost his life. Meanwhile, the family had been forced to sell a precious 15th century Pieter Breughel the ‘Younger’ painting for £6 million to pay off Sally Cholmondeley and to also spruce up the struggling Soysambu.

For historians, For Love of Soysambu, is a treasured addition on how the white settlers’ adopted in the new country, their split identity crisis, and continued dilemma after independence after political tables were turned.

Recalling 127 years of memory and over four generations is no mean task. In the colonial historiography, this book has largely trivialised the human rights abuse that took place in Soysambu and fits in the continuing justification of the colonial enterprise, the heroising of the settler economy and justifies the raw territorial appropriation.

In passing, the book acknowledges that it was Lord Delamere who engineered the passing of the Collective Punishment Ordinance of 1909, or thereabouts, where extrajudicial punishment would be mete on local communities if any of the settler’s livestock was stolen. That, notwithstanding, the fact that it was the settlers who had encroached on the community land is understated, while the suffering that the local communities faced by venturing into Soysambu.

In the study of memory, people remember what they want to remember and they tell the stories they would like to be remembered. Normally, what people deliberately forget to recount is as loud as what they amplify. The African voice in the Delamere story is missing – and they appear in Soysambu as servants, workers, and poachers. But that is how the colony was organised and Soysambu was the little corner of the Kenya colony. And reading throughout the book, one doesn’t get the feeling that Soysambu has shed its image. Not, yet.

Another surprise is that the Mau Mau war of independence, like in most of the colonial literature, is negatively depicted and overlooked. When Barnes says that ‘many people lived in fear of attack, mistrusting their loyal workers’ she must have been talking of the settlers. And how did the Delameres react to the crackdown on hundreds of thousands of Kikuyu, Embu and Meru who were forced into detention camps and villages? We are told that he protected his workers from being hurled into detention.

Memories of colonial past

But we have to forgive Juliet Barnes since she was not writing a political treatise on the Delameres as a member of the settler community allowed to make sense of the British new acquisition in eastern Africa. Rather, this is a story about the life and times of a family that had made a home in Kenya’s Rift Valley and it helps historians to look intensively into the colonial project.

More so, for students of settler economies, this is a fine book to study cultural continuity and identity. Though the Delameres had taken Kenyan citizenship after independence, the reason their holdings had survived the settlement take-over, they don’t seem to have immersed themselves into the Kenyan social and political life. But they had some good friends within the government who included Attorney-General Charles Njonjo who was on the board of Delamere Estates and who always offered some advise.

As a piece on settler narratives – or rather settler biographies – Juliet Barnes has given historians and historiographers yet another chance to scrutinise the thinking of settler families and how they would like to be viewed and remembered. There is a whole new study on settlers’ memory, which is feeding to some new intellectual discourse about race and identity and this is where this book fits as a case study.

More so, this book is about how Kenya’s white settlers curved their spaces and how they have lived within these spaces, either oblivious of the surrounding, or by simply adapting. But one thing is clear: they have retained their identity and mischief for more than 100 years.

When Tom was accused of killing two people within Soysambu, memories of the colonial past were rekindled. Even the remaining settlers saw no justification in what Tom did.

For Love of Soysambu is a fine read and Juliet Barnes has done some justice by allowing us peep into the continuing saga of the Delameres – and letting us pick from where Elspeth Huxley ended her story. There are many other stories weaved in this book that makes interesting readings.

Today, as Juliet tells us, nobody knows how the Soysambu of tomorrow will look like. It has had its history – and that history is now part of our history. For heritage buffs, this piece of history should never go to waste – for it holds the deep story of colonial enterprise.

[email protected] @johnkamau1