Shallow, predictable and very boring – the problem with Kenya’s new writers

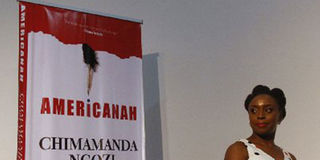

Like in everything, one has to grow. The best example is Chimamanda Adichie who has grown from her first novel, Purple Hibiscus. Her characters then were shallower and they grew in Half of a Yellow Sun and arguably became more complex, subtle and with more depth in Americanah. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- Unfortunately, much of Kenyan writing is shallow except a few familiar names. Could this be the reason why we are beaten literary award after literary award by West Africans (by Nigerians, especially) and South Africans?

- Someone once said that one small state in Nigeria has better writers than the whole of Kenya combined.

- Characters in most Kenyan novels are completely undeveloped; predictable and downright boring. They are also aloof, things happen to them but they don’t get broken or ecstatic in a way that moves the reader.

May in Ayemenem is a hot, brooding month.

The days are long and humid. The river shrinks and black crows gorge on bright mangoes in still, dustgreen trees.

Red bananas ripen. Jackfruits burst. Dissolute bluebottles hum vacuously in the fruity air.

Then they stun themselves against clear windowpanes and die, fatly baffled in the sun.

The nights are clear, but suffused with sloth and sullen expectation”.

- The God of Small Things, by Arundhati Roy:

The words above have been shaking the literary world for years.

This little paragraph has depth and some richness and subtleness to it. It gives one a reason to pick up a book in a world inundated by hashtags, tweets, Facebook memes and mobile texts.

As Annie Dillard once wrote, “Why would anyone read a book instead of watching a movie. Because a book can be literature… The more literary the book — the more purely verbal, crafted sentence by sentence, the more imaginative, reasoned, and deep — the more likely people are to read it. The people who read are the people who like literature, after all, they like what books alone have… People who read are not too lazy to flip on the television; they prefer books.”

Unfortunately, much of Kenyan writing is shallow except a few familiar names. Could this be the reason why we are beaten literary award after literary award by West Africans (by Nigerians, especially) and South Africans? Someone once said that one small state in Nigeria has better writers than the whole of Kenya combined.

PREDICTABLY BORING

Everything has its traditions and ours seems to be shallow; obsessed with externals (setting, plot and pace of the story) but rarely delves deeper into the depth of characters.

Characters in most Kenyan novels are completely undeveloped; predictable and downright boring. They are also aloof, things happen to them but they don’t get broken or ecstatic in a way that moves the reader.

Our literature is just very descriptive, rarely captivating and moving.

One very candid judge of the Jomo Kenyatta Prize of Literature once alluded to this. Looking severe, standing behind a lectern one evening during one of the Nairobi book fairs, she said: “Most of the manuscripts we received for the Prize were predictable and boring.” I almost screamed in agreement because most of the manuscripts we receive in publishing houses are very boring! And Kenyan writers hate to hear this.

However, our problem of creativity should go beyond just bashing writers. It’s a deeper malaise. Look at our arts from music, theatre and film to books. Sure, in the music front we have moved several paces ahead, but to be honest in the film and books front, we need a paradigm shift.

Writing doesn’t happen in a vacuum, it happens within a context. One can’t have good movies scripted if the writers are not creative. Taking Nigeria, for instance, it has some of the most creative writers in Africa and it has covered the entire continent with their movies. Creativity in one area of the arts is somehow connected to the others.

BACK TO BASICS

Our problem in Kenya is that we compartmentalise and demonise; writers, editors and publishers. However, the problem is that the whole arts and culture industry is in trouble; even our comedians can’t come up with original jokes.

Writers need to go back to the drawing board. A good novel is not just a string of words snaking towards the last line of the last chapter.

A good novel is feeling; let the characters feel, laugh, cry and be human instead of the robotic and forced caricatures that pass for characters in most Kenyan novels.

Kenyan writers can borrow a leaf from Russian literature. If there is an area the Russians have arguably confounded the Americans, it’s in literature.

There are five great Russian writers whose place in world literature is absolutely secure: Pushkin, Gogol, Turgenev, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. Through these writers, we get the feel of intensity and immensity; we almost see the boundless Russian steppes, the illimitable expanse of snow and the long, sad winter nights radiating with pity and sympathy that is almost divine.

These writers are full of what one critic called “sentiment, smiles, tears and passionate enthusiasms”. A good example is a paragraph off Turgenev’s Torrents of Spring:

“The ladies praised his voice and the music, but were more struck with the softness and sonorousness of the Russian language”. Turgenev goes beyond what many Kenyan writers do: stop at the singing and adds some depth to it.

One hears something beyond the song, there is softness and sonorousness. Good literature should penetrate the ground of our present (sometimes dull) reality.

Literature, as one pointed out, should “help us to see beyond the immediate world…into the transcendental dimension that frees us from the bondage of time and allows us the shock of recognition and forces us to look deeper into others and into ourselves”.

No wonder, in high school, we had people nicknamed ‘Okonkwo,’ ‘Romeo’ or ‘Juliet,’ students saw these characters in their peers and aptly named them.

This is proof that the students didn’t just mechanically read the text, they connected to it, Okonkwo jumped off the page into their immediate surroundings.

MATTERS OF THE HEART

One doesn’t become subtle — that delicate and precise quality to literary — overnight. Like in everything, one has to grow. The best example is Chimamanda Adichie who has grown from her first novel, Purple Hibiscus. Her characters then were shallower and they grew in Half of a Yellow Sun and arguably became more complex, subtle and with more depth in Americanah.

Some books have the ability to make readers feel a constriction in the back of their throats, a flutter in the belly and even a tremble through the body and afterwards leave them with a sad, haunted look when the book ends. This is emotional connection between the fictional characters in a book with the reader, much the same way characters in movies or soap operas jump off the screen and cause tears to flow.

We know they are just acting but for a fleeting moment, we forget it; connect and identify with them and even empathise with them. It’s not just characters that need depth, even places do.

In Americanah, Chimamanda describes some American cities with relish. “Philadelphia had the musty scent of history. New Haven smelled of neglect. Baltimore smelled of brine, and Brooklyn of sun-warmed garbage. But Princeton had no smell”. Each city has its own character and it’s aptly highlighted in a memorable way.

Kenyan writers need to write characters that look inward, characters with feelings, characters that can feel others and be felt by the reader.

And these characters should be developed to become more mature in reasoning and emotionally even as they grow physically across the book.

Most of the time, we seem them grow physically but we need incidents that will blow open their minds and their hearts so we connect with them. That’s the kind of literature that never dies.

That’s how Shakespeare wrote, for the heart, not for the head. And matters of the heart are the same, for every generation, no wonder Shakespeare lives on forever.