Nairobi is a safe and inspiring home for many Ugandan artists

Jackie Chandiru during the interview at Nation Centre on March 18, 2021.

My colleague Angela Oketch’s story in the Sunday Nation of March 28 on pop star Jackie Chandiru’s battle with addiction touched me at many levels. To begin with, Ms Chandiru, best-known for her provocative pop hit ‘Gold Digger’, is my compatriot, a typical new Ugandan, with a father from Arua in West Nile and a mother from Kampala. Indeed, one of her praise names is “Queen of the Nile”.

Secondly and more importantly, though not personally known to me, Jackie Chandiru belongs to that generation of young people whom I encountered and taught on my return to Makerere in the early 2000s. These were a crop of eager, enthusiastic and optimistic human beings, determined to make a mark on their society and the world, as many of them have, indeed, done.

But they were beset by a forest of problems, among them the rabid and cynical materialistic (“money talks”) culture that shows no sign of changing even today. Then there was the “celeb myth”, that a talented artiste, as Jackie Chandiru, with her strong voice and electrifying stage presence, turned out to be, had to live “big” and expensive lifestyles.

Worst of all was the persistent and malicious objectification and stereotyping of the female university student as a frivolous idler and plaything, there for any comers and takers. This made our students prey and victims to the hordes of predators in and around Kampala, including marauding tycoons, bored expatriate “experts” and execrable politicians. The women’s halls of residence at Makerere became hunting grounds for all sorts of hedonists loaded with their filthy and often ill-gotten riches.

Ugandan musician Sammy Kasule.

Some of our sisters, indeed, succumbed to the onslaught and cynically subscribed to lifestyles that they called the “three Cs”, namely, cash, cars and cell phone. Whoever was prepared to offer these was welcome to their company. This degradation of relationships is actually reflected, and criticised, in Jackie Chandiru’s ‘Gold Digger’ lyrics.

This stereotyping and objectification of university women, which is a form of misogyny, I think, is the background against which Jackie Chandiru’s harrowing story may be understood. Her tragic slip into addiction was easily understandable, and her brave struggle to free and rehabilitate herself should be laudable.

Shockingly, however, Ugandan society seems to have adopted an implacably callous and unsympathetic attitude towards this talented young woman.

My feeling is that the Ugandans’ “toxic” response to Jackie’s problems arose from the likelihood that they had already stereotyped and labelled her. Even as they admired her talent, they had been conditioned not to expect much of “her and her likes”. Kampala was, and is, immovably prejudiced.

The most touching and uplifting point I got from Jackie Chandiru’s sharing with Angela Oketch was that she trusted that Nairobi, where she is now taking refuge, would be a haven of healing for her. I do hope and pray that this will come true. Nairobi and Kenya generally has been a safe and inspiring home for many Ugandan artists, ranging from visual artists through writers to musicians, for a number of reasons.

At their best, Nairobians have always had that attitude of acceptance and “letting you be” that is extremely reassuring for people fleeing from some form of rejection, threat or persecution. In artistic and academic circles, the acceptance is almost unqualified, probably dating back to the good old days of our undiluted East African Community.

The availability of outlets for creative expression and the responsiveness of most audiences, coupled with the technical dynamism of industries like publishing, recording and filming are also motivating factors.

Nairobi and Kenya have thus been the cradle of the best works by such stalwart artists as writers John Ruganda, Okot p’Bitek and Barnabas Kasigwa, visual artists like Jak Katarikawe, Leonard Kateete and Nuwa Wamala Nyanzi, all of whom first arrived here as refugees. The link with musicians is even wider and longer.

Household name

George Senoga-Zake was already a household name in Kenya when I got here in 1977. He was a naturalised Kenyan, having teamed up with Dr Washington Omondi, Thomas Kalume, Mwalimu Peter Kibukosya and Graham Hyslop to compose Kenya’s National Anthem in 1963.

Senoga-Zake’s long residence in Kenya and his extensive research into Kenyan music led to his long-running VOK/KBC radio programme “Folk Music of Kenya”. He also wrote an absorbing and illuminating book, with the same title, out of the experience.

Prof Senoga-Zake was a long-time colleague of mine at Kenyatta University, along with Dr Omondi. We also worked there with George Kakoma, another Ugandan musician, who had composed the Ugandan National Anthem in 1962. Some company, wouldn’t you say?

Later we also hosted Dr Anthony Okello, the brilliant composer and accompanist, who had been one of the founding lecturers at the Music Dance and Drama department at Makerere. Dr Okello also taught briefly at Maseno University in its early days.

Out on the popular music scene, a long line of Ugandan musicians has had Kenyan links. The location of the early recording studios almost exclusively in Kenya, meant that most Ugandan musicians depended on Kenya for the production of their music. In the process they interacted closely with their Kenyan colleagues and they inevitably influenced one another.

Charles Sonko and his sister Frida Sonko, for example, who recorded with Equator Sounds, were obviously influenced by the “twist” maestros, John Nzenze and Daudi Kabaka, in their later performances.

Incidentally, Daudi Kabaka, with whom I became friends in his later years, was raised mostly in Uganda, and I used to joke with him that he spoke more fluent Luganda than I.

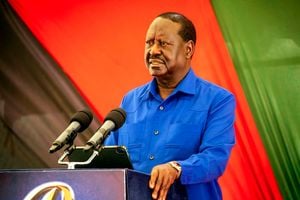

In the late 1970s and most of the 1980s, there was a regular exodus of Ugandan performers to Kenya. Those who were there then will remember artists like Peterson Mutebi and the Flames, who often performed at the Small World Club, and Sammy Kasule, of “Shauri Yako” fame, who I believe was regular at the Carnivore.

So, our sister Jackie Chandiru will be on a long and well-trodden road if and when she connects with Kenyan fellow musicians. Kenyans will certainly not treat her harshly.