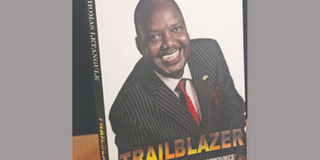

Ex-IEBC commissioner Letangule on his rise from grass to grace

Ex-IEBC commissioner Letangule on his rise from grass to grace. PHOTO| FILE| NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- The commissioners were ill prepared but on the outside they put on brave faces. The commission was caught in a catch-22-situation. Should they go manual or proceed with the electronic gadgets?

- A decision by the court to extend the election date from December, 2012 to March 4, 2013 was a reprieve to them, but technological challenges still arose.

- The failure of the EVID on the material day is what broke the camel’s back.

When the names of the commissioners who oversaw the first election after the promulgation of the new Constitution are engraved in the annals of Kenyan history, a certain epithet of one man from the rural, marginalised Ilchamus community will be first among equals.

Thomas Letangule, a former commissioner of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) and a man known during the 2013 General Election as a fierce defender of the electoral commission, has penned an incisive memoir, recounting his rise from grass to grace.

The man from Baringo Central takes us from a tiny village called Ng’ambo in the dry Baringo, the home area of President Daniel arap Moi, through his brief political life and later to being appointed a commissioner for the IEBC.

The 18-chapter book, with a foreword by Pheroze Nowrojee, delves into the making of Mr Letangule after his uncle, Hosea, took him to school, to his becoming a budding lawyer in the mid-1990’s to a public officer.

After graduating with a Law degree from the University of Nairobi, Mr Letangule works under some of the best legal minds and ultimately opens his own law firm.

He takes up cases in support of the minority. With his stock rising, he decides to venture into politics in 2002 to contest for the Baringo Central constituency seat that had been left vacant by the retirement of president Moi. He is up against Moi’s son, Gideon Moi and a strong wave of Kanu. He is on a Narc ticket. He sails through in the primaries but is forced to drop his bid in favour of Mr Moi by the powers that be.

His second stab at the seat fails dramatically.

There is a chapter solely dedicated to the work of the IEBC in 2013. ‘IEBC and the Inside Story of Electoral Intricacies’ looks at the intrigues of the Ahmed Issack Hassan-led commission. The commission was in a race against time. The procurement of electronic gadgets had the agency in jitters.

“The previously calm waters of the nation’s political aura were stirring up into a whirlpool of heated debates. The atmosphere was getting charged with every passing day,” he writes.

The commissioners were ill prepared but on the outside they put on brave faces. The commission was caught in a catch-22-situation. Should they go manual or proceed with the electronic gadgets?

A decision by the court to extend the election date from December, 2012 to March 4, 2013 was a reprieve to them, but technological challenges still arose.

The failure of the EVID on the material day is what broke the camel’s back. Complaints poured from every corner of the country and the commission decided to go manual. The servers then crashed and the electronic transmission of results failed. Manual transmission of results was declared but party agents kept on disputing the results at Bomas of Kenya. It took the intervention of Mr Hassan and the author to order agents out of the national tallying centre.

After six days of ups and down, the chairman announced Uhuru Kenyatta as the fourth president of Kenya.

‘Tragedy Strikes’ offers a glimpse to what followed after the disputed results. A total of 190 cases were filed in the High Court and magistrate’s courts with Cord filing a petition in the Supreme Court. Mr Letangule was appointed to head the IEBC Dispute Resolution Committee. In all they dealt with over 2000 complaints.

April 10, 2013 marked a low point in the life of Letangule. His third wife, Esther, who was expecting their third child, died in the hands of negligent medical staff. She, however, left behind a baby girl aptly named Namunyak, ‘the lucky one’.

In ‘My Desire for my Country,’ the author is looking forward to a day when Kenya will move away from the current presidential electoral system to when the political party with the most seats from the 290 constituencies would form the government of the day. He writes: “This I believe would eliminate the need for presidential candidates and their running mates to focus on areas or communities where they feel they would get the most support with regards to numbers. This way, the campaign would be equalised across all voters, irrespective of where they come from, with the understanding that every corner of the country matters in the same way.”

The title of the book is apt as every triumph in the book captures a first of sorts. His rise from an ordinary herds boy to a position where the hopes and aspirations of an entire nation rested on his judgment is trailblazing. He became the first lawyer from his community.

His daughter, Joan, is the first Ilchamus girl to study law. “It is a source of pride and joy for me that my children are turning out to be trailblazers, and in their own way,” he writes.