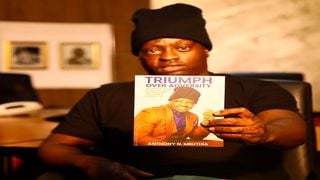

Anthony Mbuthia displays a copy of his book is titled ‘Triumph over Adversity’.

| Billy Ogada | Nation Media GroupLifestyle

Premium

My post-election scars are part of who I am now

What you need to know:

- Anthony Mbuthia is now a businessman in the US, running a company called Picha Fine Productions that handles photography and videography.

- Mbuthia is 26-years-old now, and though he will never forget, he has since forgiven and gone on to forge a fulfilling life for himself with the help of others

It is Wednesday at 11am when Anthony Mbuthia walks in for an interview wearing a beanie hat.

“The jetlag hasn’t kicked in yet,” he says, referring to his trip from the US, having landed in Nairobi about 12 hours earlier. He will be heading for Dubai the next day, he says.

A man of medium build, he is one of the very few people who have been allowed to take national ID and passport mugshots with a hat on. He produces his Kenyan ID, issued in the US, to prove it.

This is, however, nothing to celebrate because the black beanie is part of the episodes in Anthony’s story of sustaining scars when a church was set ablaze at the height of the 2007/8 post-election violence and the difficult days that followed, which saw him operated on more than 100 times in the five years that followed.

December 2007. Will Mwai Kibaki retain his seat for a second term or will Raila Odinga oust him? That was the question on the ballot in the December 27, 2007 polls.

Anthony had just turned 10 years old on October 25 that year and could hear the political chatter, but his young mind could barely grasp. People argued so strongly for one candidate and vehemently dismissed the other.

He preferred to play football with his friends who had nicknamed him Rooney, (former England player who is the manager of EFL Championship club Birmingham City), and tend to sheep.

He was born and raised in Yamumbi on the outskirts of Eldoret town. This December found him in Kiambaa, about a 30-minute drive away, as that is where his maternal grandmother lived. Anthony, his mother and two siblings had travelled to Kiambaa to celebrate Christmas.

On the day of the elections, their mother left for Yamumbi, as that is where she was registered to vote, leaving them behind.

The presidential election ended up being disputed and tension rose.

Anthony Mbuthia survived the torching of the Kenya Assemblies of God Church in Kiambaa, Uasin Gishu County in January 2008.

January 1, 2008. This was supposed to be a day of celebrating the New Year, but there was little to celebrate for Anthony, his grandmother, siblings and other relatives in Kiambaa.

It found them living within the vicinity of the Kenya Assemblies of God church, too scared to stay in their homes as violence took root. Most Kiambaa residents were backing Mr Kibaki.

“(When) Kibaki was declared the winner of the contested election, hundreds of Kiambaa residents came out of their homes to celebrate. It was not long before we heard people saying that chaos had erupted in different parts of the country,” recalls Anthony.

Despite the tension, the New Year’s Day appeared fairly normal until around lunch hour when all hell broke loose. A group of assailants stormed in, spoiling for a fight. Anthony and others dashed into the church. Their hearts pounded as the roof was pelted with stones.

“Everyone panicked, and a stampede ensued as the women and children outside the church rushed to get inside. I rushed inside, and pandemonium separated me from my siblings,” Anthony recalls.

Soon, they smelled smoke. The church had been set ablaze.

“I saw huge flames penetrating inside the church through the ventilation. Since the church was built of wood, the fire spread quickly. I panicked. A serious stampede ensued as everybody tried to escape through the few available exits,” recalls Anthony.

“I moved towards the altar, searching for my exit. I kept crawling on the floor while covering my head with my hands. People kept pushing and shoving me aside and stepping on me, but I kept fighting to get out. The next thing I remember is that I found myself outside the burning church. I still can’t remember how I escaped from the fiercely raging fire gutting the church. I felt like I had been lifted by a rescuing force and then transported and dropped safely outside the church building. As soon as I was outside, the building collapsed behind me in a blazing inferno.”

Perhaps because of adrenaline or whatever else was powering his body, he did not realise he was burnt.

After leaving the church, he made his way towards his grandmother’s house and he remembers coming face-to-face with a machete-wielding attacker who gave him two options.

Anthony Mbuthia now lives in the US with his family.

“I told him that I was trying to find my way back to my grandmother’s house. He quickly raised his machete and I thought he would kill me. Instead, he ordered me to turn around and walk in the direction of the main road, which he said was the road that the people of Kiambaa village were using to flee. I stood there confused, thinking I should dash to my grandmother’s home. Then, as if reading my mind, he told me that if I insisted on going to my grandmother’s house, he would kill me. Quickly, I heeded his instructions,” he says.

On reaching the main road, he was led into a pick-up. He would later learn that the other passengers in that ride to the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) were burn survivors from Kiambaa.

April 2008. This is the time Anthony and other children who were burnt in the Kiambaa fire were transferred from MTRH to the Kijabe Mission Hospital. By then, Anthony had undergone a series of surgeries; some successful and some not so much.

At Kijabe, the patients got into contact with a doctor who recommended that they be flown to the US for specialised treatment. Appeals were made and politicians mobilised for funds to facilitate the journey to the US.

President Kibaki’s government stepped in and offered to fund their accommodation and treatment in the US.

“When the appeal for monetary donations was made to the public through televisions and newspapers, the public responded quickly by generously giving what they could afford,” says Anthony.

“The committee also organised for us to visit the State House in Nairobi and meet President Kibaki. I was so excited to meet the President and other government dignitaries.”

March 9, 2009. That is the day Anthony and the three other children affected flew to the US, each accompanied by their mother. The initial plan was to have them there for about 18 months before they returned to Kenya. But as it would turn out, each of them is now living in the US.

“They are all grown now. The first one, Mary, is married. She is also in Sacramento. She lives in California, and she’s married with, I believe, four beautiful babies. The second one, Mercy, finished school this year, I believe, at UC Davis (University of California, Davis). She is also in a relationship, married, and has a baby now. And then myself, niko soko (I’m in the dating market), and then Jedidah, the last one, is in university right now. She is studying at Sacramento State University. Everyone is doing well. None of us gave up,” he says.

In between the surgeries, the children started schooling in the US. Anthony remembers struggling to communicate as he was told he had an accent and was also bullied because of his scars.

November 27, 2013. For the first time since leaving Kenya, Anthony and his mother got to meet the other children in the family. The family applied for asylum status that was granted by the US government, enabling Anthony’s brother and sister to travel to the US.

Their father, Peter Mbuthia, would join them later. Their house and business in Yamumbi had been burnt down during the post-election violence. Now, the family is establishing itself in the US – in Sacramento, California – and both parents are working there.

“I thank God for blessing my family and me through my pain,” says Anthony.

“I genuinely believe that my burning at the church was a conspiracy from the universe to create the opportunity for me to come to America, where a beautiful infrastructure supports creativity.”

In 2019, Anthony’s father, Peter Mbuthia, released the book, Scars of a Nation: Survivor of Kiambaa Church Massacre and the Elusive Justice. That same year, the father also publicly came out to say he was a prosecution witness at the now-discontinued trials at the International Criminal Court.

Anthony is now a businessman in the US, running a company called Picha Fine Productions that handles photography and videography. He gets hired to capture moments on camera at weddings, birthday parties, and takes baby bump shoots. That enabled him to buy his house last year.

“I want people to know that even though the world can sometimes be cruel, we can always make it a better place to live in by responding positively to any kind of provocation,” says Anthony.

“You have three choices when a bad thing happens. You can let it define you, destroy you or strengthen you. Also, you can choose to be bitter or better. You can let the wrong thing break you or make you. You can choose to be forever a victim or a victor. For me, I let my tragic situation strengthen me. I cannot remove my scars. Instead, I chose to embrace them as part of who I am,” he adds.

Anthony Mbuthia, a survivor of the 2007-2008 post-election violence, now lives in the US.

Anthony also runs a comedy YouTube channel called Cheka TV, which has 39,000 subscribers and whose videos have amassed six million views combined. His entry into that space was a YouTube channel called A Kid with a Beanie.

December 28, 2019. For the first time since flying to the US for treatment, Anthony returned to Kenya. One of the places he visited was the Kiambaa church.

“I was shocked to see the graveyard where the people killed in the church fire were buried. The scene resembled a horror movie more than reality. I felt so sorry for the victims, and as I sat there viewing the graveyard, I kept imagining that I would have been one of the victims lying there had God not saved me,” he says.

In the US, he says, sometimes he is asked why he is a church person despite that incident.

“Some of my American friends would ask me why I always talked about going to church, yet I was burnt in a church. And I would tell them that despite that one terrible experience, it is still my safe space. Church has helped me to avoid many negative social influences I fear I would have been exposed to if I hadn’t committed to it. It has contributed so much to shaping who I am,” he says.

“I was able to forgive the people who did what they did to me. And it’s funny because I can relate it to that thing where Jesus, when he’s at the cross, he says, ‘Forgive them for what they know not what they are doing.’”

October 21, 2023. This is the day Anthony launched his book Triumph over Diversity, which captures his ordeal and how he shook off his troubles to find a purpose in life. Anthony insists in the book that he is not after getting sympathy.

“(The story) might sound sad sometimes, but I do not wish for you to feel sorry for or sympathise with me,” he writes.

“I wrote Triumph Over Adversity to tell my story, and to tell it from a perspective of faith; a perspective of somebody who has gone through so much, who was given everything to give up but still didn’t.”

In his foreword in the book, Mark Mwangi, an apostle of the House of Glory Church in Sacramento, explains how the church launched Anthony’s career.

“He joined the church media,” writes the preacher, “He discovered his passion for photography and video coverage. He has since gone ahead and built a career out of it.”

Anthony’s first photos were taken using the church camera before he got inspired to buy his. He says he ventured into self-employment because he found it hard to get a job.

Anthony Mbuthia, a survivor of the 2007-2008 post-election violence, now lives in the US.

“In my senior year in high school, I used to apply for jobs where I would be interviewed, but then they wouldn’t hire me, which made me think I was unemployable,” he says.

“I was convinced I would never get a job, motivating me to become my (own) employer.”

Another foreword writer in the book is former BBC foreign correspondent Karen Allen. In 2008, Karen got Anthony to tell the story of his love for football, his admiration for the Manchester United football club and how his peers called him Rooney.

That later saw Sir Alex Ferguson, then the Manchester United manager, write a letter to him, dated September 1, 2008.

“I hear that you have been through a terrible ordeal recently, and I want you to know that the players and I are thinking about you and wishing you a quick recovery,” wrote the legendary manager.

Antony says: “I was extremely elated about Sir Alex Ferguson’s message.”

Today, Anthony is particular about not using the word “victim” in his Kiambaa tragedy story. He prefers “survivor”.

“A victim is somebody who’s always feeling bad about themselves regarding what happened to them. But for me, I changed that. And as soon as I saw that I was a survivor, I took that and ran with it. And I believe that God made everything possible,” he says.

To that child being bullied due to their looks, Anthony has a word of advice.

“Don’t internalise it. Bullies tell you things because they are insecure. There are things they are dealing with themselves. Never think that what they are telling you is true. What is within you should echo louder than what you are being told from outside.”

“One thing that changed my mind is that I looked at myself in the mirror and I realised I was going to have these scars for the rest of my life,” he adds. “I am not a bitter person. You know, I chose to be better.”

And to anyone who would ever want to be used to harm others for political causes, Anthony has a message of caution.

“If I were you, I wouldn’t do that,” he says. “You’re affecting the life of not just the people around there, but a lot of people on the whole.”

After the interview, he ambles into the streets of Nairobi, confident in his black beanie.

“You know, it’s become part of me,” he says of the beanie.

“In Kijabe, they used to give me the nets that surgeons cover their hair with. This was to prevent infection. I would keep changing them, and after a while, that became part of me. When I would take them off, I felt like I was naked, like I just needed something on me. I remember that at one point, somebody gave me a beanie when my scars started to heal. Once I put the first beanie on, it became part of me,” he says.

Bar his facial scars, he may pass as any other young man on the streets. You can’t point out a man who has been to hell and back; a man whose heart stopped during one surgery in the US when he was in Eighth Grade and had to be resuscitated by medics called from a nearby hospital.