Fat-shamed in childhood, Stephen Ogweno is now a celebrated world health champion

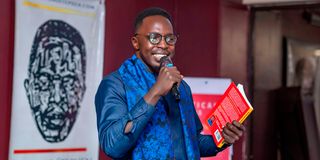

Stephen Ogweno a non-communicable diseases advocate, at the World Heart Summit held in Geneva, Switzerland in 2022.

He was the overweight boy. The object of ridicule. The boy who couldn’t fit in regular uniforms.

Not many understood what was happening in Stephen Ogweno’s body, not even himself at first. He had childhood obesity and was way heavier than his peers.

Whenever a relative held him aloft as a child, he or she could not help but comment on his literally bouncing and chubby physique. But he had a big problem within him.

“Being born with obesity had its own challenges. I developed gastroesophageal reflux disease (Gerd), a condition whereby after intake of food, it constantly regurgitates. This in turn affected my dental health. My teeth decayed rapidly,” he tells Lifestyle.

As a stout boy fast speeding to his teens, he was the perfect recipe for ridicule about his stocky size. He recalls an incident that occurred to him in Class Seven that is engraved in his mind.

“My age mates were undergoing adolescence and their shoulders were broadening. They would showcase their muscles when all I had was a mass of fat. I was not turning into a man while everyone else was. The stigmatisation and discrimination amongst my peers due to my obese nature would really affect my self-perception. But I found solace in beating them in school work,” he shares.

Fast-forward to today. The 27-year-old now epitomises three adjectives: an optimist, visionary and enterprising Kenyan. He has carved a niche in the public health space, primarily in championing the awareness of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like cancer and diabetes through community health literacy campaigns and medical camps and through the use of innovation.

He does this through Stowelink Foundation, an organisation he established in 2016. He is a trailblazer as he sits in a number of boards such as the World Health Organisation (WHO) NCD labs committee as a steering member. There is also the World Obesity Day Global Planning committee where he is a member.

Stephen also has a couple of accolades under his name. He made a presentation at the Royal College of Physicians during the 5th Commonwealth Nurses and Midwives Conference in the United Kingdom in 2020. He represented Kenya in that.

Two years later, in 2022, he dazzled on a panel discussion made up of a lead team of World Health Organisation personnel at the World Heart Summit in Berlin, Germany, where he represented the country.

This is a complete 360 from the ridiculed boy in his childhood.

When he was a child battling obesity, he was battered by many waves. But his family hardly regarded obesity as a sickness. Rather, they considered him very healthy. They also would not acknowledge he had Gerd. They thought the constant regurgitation of food was a distasteful act he would pull for fun. For him, it was something involuntary that he had no control over. He would get continuously nauseated and would not even sleep in certain positions.

Stephen Ogweno at the World Heart Summit in Geneva, Switzerland in 2022.

He struggled with the condition and on his first day of admission in high school, all the clothes available to be given to students, none was big enough for him.

“For my age and what I was expected to be, I was overweight. I wouldn’t fit into my uniform. The school had to make arrangements for custom-sized uniforms to be made,” he says.

By the time he was in secondary high school, Stephen had been accustomed to the stigma and had therefore grown a thick, defensive skin. His mates would see the chunkiness whilst the Gerd was mildly discomforting. He thus had to struggle with it inwardly.

“Being optimistic, I accepted the condition by knowing that there was nothing I would do at that point. I had to live with the challenges. Also, according to experts and research, someone born with obesity is supposed to have had hypertension at 18; developed type two diabetes at 25. And by the time they are 35, they would have already had other chronic diseases,” he notes.

In full knowledge of the complications that he would develop as he grew older, he decided to be intentional with losing weight. He committed himself to becoming physically fit to beat obesity. He joined both the handball and rugby teams and did daily sprints around the field in high school.

Interestingly, after all this, he didn’t lose weight. He had a lot more muscle fat and bone density and he weighed 112 kilogrammes.

Just before joining university, around 2014, Stephen lost three of his friends to diabetes and stroke. The demise really stressed him as he wondered why the friends were losing their lives to diseases early on thought to be for older people. The unfortunate occurrence made him defer the information technology course he had been selected to pursue at Kenyatta University. He chose population health instead.

“While going to university, my mind was settled on educating people about non-communicable diseases and chronic illnesses. I was certain these friends did not die because of lack of resources or support to manage the condition but probably, they didn’t know what they suffered from and only realised at a late stage,” he says.

In 2015, while a first year in Kenyatta University, he was so passionate about shedding light on NCDs amongst young people that he founded the Stowelink Foundation to advocate for NCDs, educate and ensure people have access to diagnostics while leveraging on technology to spread the awareness on these diseases.

“From the lack of treatment of the disease, I had developed complications. During my second year of study at Kenyatta University in 2016, there was a six-week period that I could not eat at all. The food constantly regurgitated. I would not concentrate and my physical health was affected. I had to seek medical care and that was when I got diagnosed with Gerd. I was given medicine, then put on a healthy diet and physical exercise. These were things I was already doing. Since then, I have been generally okay and the disease is under control,” he notes.

It was also in university that he consistently worked out, adapted a lifestyle and eating routine that he underwent a massive physical transformation. He got into shape that he was a finalist in Mr and Mrs Kenyatta University bodybuilding competition during his fourth year of study in 2019.

As the founder of Stowelink, Stephen started spearheading impactful projects. In 2016, they had Project Alpha, which was focused on cancer sensitisation among students. The project incorporated art and fun things like photography and a poetry contest to have young people on board who considered health to be complex but Stowelink made learning fun. In 2017, they had “My Heart KE”, a project focusing on cardiovascular health and they leveraged on the creativity of young people to spread awareness on health issues. They did cardiovascular screenings through blood tests in various labs in Kibera and Githurai. The project was supported by the millennium fellowship in terms of implementation and they worked with eight universities around Nairobi.

“We developed a health tech application, “My Heart KE”, which flopped terribly, and down the drain went all my savings in university. This was because the app’s language was too technical and it was only the medical students who enjoyed interacting with it,” he says.

But not all was lost as the project led Stowelink to gain public recognition after starting a poetry and art contest that ended up becoming very popular. It attracted about a million people who interacted with their content. The poetry contest was spread in four East African countries. Stowelink would go on in subsequent years to hold noble projects like the “Drug Free Youth” in 2018 that even had the National Authority for the Campaign against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (Nacada) partner with them. And in 2019, they held the “Coz I am Happy” mental health campaign amongst the youth.

“In 2020, Stowelink decided to take things a notch higher. We worked with Vihiga County to be able to support NCD clinics that were closed because of Covid-19. We formed the first working technical group for NCDs in Vihiga, where we advocated for an increase in the county government budget for the diseases — which was effectively increased. We created five community groups of people living with NCDs in Vihiga County. We were there for a whole year, implementing this project, funded by NCD alliance and the Danish NCD Alliance,” he narrates.

It was at the height of the pandemic that they started the NCD 365 that is by far their most successful and impactful project. It was aimed at educating the masses by the use of technology.

“Each single day in 2020, the 365 days to be specific, we did a poster on creating awareness and sensitising on non-communicable diseases and we shared on Stowelink social media platforms and our partner’s online pages. This project would spread and was implemented in eight Sub-Saharan countries and in 2020, we had 27 countries on board to implement the NCD 365 project,” the medic explains.

The NCD 365 project by Stephen’s Stowelink organisation has grown in leaps and bounds such that there is an application called NCD 365 aimed at creating a real-time experience for users by connecting them with support groups of people living with non-communicable illnesses. The app updates them on various medical camps, providing various mental health tests and helping to keep track of one’s health record.

“This year, Stowelink is working on a project that seeks to show the youth the connection between NCDs and climate change. The two relate at problem and solution level because if you, for instance, stop smoking cigarettes which cause lung cancer, you in turn reduce the effect of the smoke on the ozone layer. This project will be funded by AstraZeneca and it will feature 18 universities as it targets the youth,” he says.

Stephen is also the co-founder and chief executive officer of Lifesten Health, a Rwanda-based consumer-focused digital health company that conducts awareness on and management of NCDs, rewards healthy lifestyles with the goal of reducing illiteracy on non-communicable diseases and improvement on access to early diagnostic services. An entrepreneurial acumen is also rolled up the 27-year-old’s sleeves as he is the co-founder of Info4food Africa, a venture that prevents wastage of food through drying of fruits and vegetables using low technology dryer and has impacted 821 farming households in Zambia, Uganda and Kenya.

On the leadership front, Stephen, an alumnus of the Yali Regional Leadership Centre East Africa, under the civic leadership category. He is the co-founder of legacy leadership Africa, an organisation that seeks to mentor a generation of smart young leaders.

The public health advocate is also the brainchild behind two Udemy courses, namely non-communicable diseases for public health and the entrepreneurship mindset. Both courses have over 11, 000 people. He is also a scientific researcher having published seven scientific research publications and contributed to six policy briefs and opinion pieces.

On what adds fuel to his fiery fire in championing for NCDs awareness, Stephen determinately shares that is the apparent fact that as an organisation they can actually do a lot to change people’s lives. He vividly recalls in 2017 how, during Stowelink’s third year in operation, they came across a university female student during a screening outreach who had stage one knee cancer and she was not aware about it. They rallied funds and the lady was flown to India where she got well and came back to even start playing basketball.

“Seeing those changes and how we have been able to affect people’s lives directly is so fulfilling. In Vihiga, for instance in 2020, we greatly assisted people living with stroke, diabetes who had been forgotten because of Covid-9. Through the initiative, we brought them back to life, giving them care. We saw to it that they got better mental care. Their health was suddenly improving,” he offers.

Stephen hopes to build a legacy around contributing to a society with reduced cases of NCDs since, according to statistics, over 55 per cent of hospital admissions in Kenya are because of NCDs. Also, three out every five deaths are attributed to these diseases. NCDs are expensive to manage and would single-handedly change one’s social class in the society. They affect one’s livelihood and, sadly, medical insurance does not cover as much.