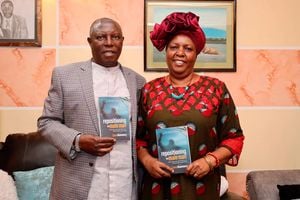

Polycarp Ngirinya with his wife Mellen Ngirinya at Utalii Sports Ground in Nairobi on September 7, 2024.

"It wasn't easy to find a woman to marry. I tried 12 women. But those are the ones I can remember. Each time I thought I'd found the one, they'd find out I had sickle cell, and their parents would tell them not to marry me, warning them that I would die soon and leave them widowed with children," says Polycarp Ngirinya Wafula, a 41-year-old.

For many Kenyans living with chronic illnesses that require constant care and hospital admissions, getting a life partner can be a daunting task. The disease is always the third partner in the relationship.

Polycarp, who has been living with sickle cell anaemia since childhood, says to cast the net wider, he even tried wooing women from other tribes.

Growing up in Budalangi, Busia, his condition seemed to define him, as if written all over his face.

“Some were from my tribe, some from my locality, and others from different tribes,” he says.

Constant rejection due to his illness surrounded him like a cloud. Some people saw him as an outcast. He was often given cruel nicknames like "wekhufwa," meaning "the one who will die soon."

"It was painful," Polycarp admits, "but it didn’t break me."

Instead, he turned his condition into a test to determine whether a woman could truly love him.

“If someone showed interest in me, I’d tell her immediately that I had sickle cell. If she walked away, I knew she was not the right one for me,” he says.

Polycarp’s strategy, though seemingly peculiar, he says, protected him from heartbreaks.

After 12 failed attempts, he met Mellen Ngirinya, who would eventually become his wife.

“I used the same approach with her,” Polycarp recalls.

“I told her I had sickle cell right away. To my surprise, she stayed. She is a hero. My angel sent from above,” he says as he looks at Mellen’s face with so much love and appreciation.

Eight years

Mellen, 29, chimes in with a warm smile, saying, “You know, love makes you say yes to anything. When he told me about his condition, I didn’t have second thoughts. I knew we could make it work.”

The couple married in 2016 and have been together for eight years with no regrets.

“I don’t regret saying yes to him. He is my world,” Mellen says.

Their relationship is grounded in mutual respect, love, and unwavering support.

Mellen also serves as Polycarp’s caregiver, ensuring he receives the treatments and medications necessary to manage his condition.

The couple says they have learned to take one day at a time. Polycarp quotes Matthew 6:34 from the Bible: “Refuse to worry about tomorrow, but deal with each challenge that comes your way, one day at a time. Tomorrow will take care of itself.”

Polycarp and Mellen Ngirinya on September 7, 2024.

This positive outlook has carried Polycarp through a life filled with challenges.

His journey with sickle cell anaemia began at the age of two. The diagnosis changed his life, marking the start of regular hospital visits, blood transfusions, and daily medication.

It was not until Polycarp was 13 years old that he fully grasped the illness that he had.

“My mother explained that I would have to live with sickle cell for the rest of my life and depend on daily medicine,” he recalls.

As a teenager, he faced stigma not only from peers but also from teachers, who excluded him from sports for fear that he could not handle the strain.

"It was hurtful," Polycarp says. “People would say things like, ‘You can’t do this or that because you will die."

Three children

In his family, he is the only one who carries the genetic mutation.

“I come from a big family, and I am the only one with sickle cell anaemia in my nuclear family. But from my maternal side, we have others also with the disease.”

Yet despite these setbacks, Polycarp was determined to build a family of his own.

Today, Polycarp and Mellen are the proud parents of three children, all carriers of the sickle cell trait, though none have the full disease.

"Raising a family has been a blessing," Polycarp says. “It’s not always easy, but we’ve made it work. Plus, I don’t feel like my condition is barring me from playing my role as a father. I can do what other parents do.”

The couple’s support system includes monthly check-ups at Baraka Health Center in Nairobi, where Polycarp receives treatments to manage his condition.

These visits involve routine blood tests to monitor his haemoglobin levels and prevent crises—painful episodes caused by sickle-shaped red blood cells clumping together.

Polycarp has learned to manage his condition through proper hydration, avoiding strenuous activities, and staying warm during cold weather.

“In a typical year, I might have to go to the hospital four to five times for more serious crises,” he explains. “But with proper management, I can avoid many severe episodes.”

Yet living with sickle cell anemia is not without its financial strain. Daily medications, monthly check-ups, and occasional hospital visits add up to their burden.

Polycarp Ngirinya during an interview in Nairobi on September 7, 2024.

"We rely on medical covers like NHIF [National Health Insurance Fund] for hospital bills, but we have to set aside a budget for medications," Polycarp explains.

The family spends about Sh150 per day on essential drugs like folic acid, zinc, and painkillers.

Hydroxyurea, a drug that helps suppress crises by increasing fetal haemoglobin, is also a significant but worthwhile expense.

Despite the many challenges of living with a condition that many view as a death sentence, Polycarp has built a fulfilling life with his wife and children. His message to others living with sickle cell anaemia is one of acceptance and resilience.

"You have to accept your condition," he says. “Once you accept it, you can start living your life. Follow your doctor’s advice, take your medications, and take care of yourself. You can live a full, happy life, just like anyone else.”

Expert view

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), two-thirds of people affected by sickle cell globally live in Africa.

It is the most prevalent genetically acquired disease, but survival statistics are just estimates.

Dr Moses Odongo, 39, leads the Sickle Cell Clinic in Mathare, Nairobi working with German doctors to provide care to over 1,000 patients.

He says that every week, the facility can diagnose approximately three new cases, mostly children born with sickle cell disease.

“This is a high number considering the catchment area versus the number of positives. The number could be high because the awareness about the disease is not that much,” he says.

One of the clinic's major challenges is the accessibility of affordable treatments like hydroxyurea.

“The price of hydroxyurea depends on where you are getting it. For us, we sell it at Sh20 per capsule, but it’s difficult for most patients to buy even at that cost long-term,” Dr Odongo says.

Mellen Ngirinya during an interview at Utalii Sports Ground in Nairobi on September 7, 2024.

He notes that the lack of a widely circulated liquid formulation for children who cannot swallow pills adds to the financial burden.

Another issue is the insufficient support from the Health ministry.

“While NHIF covers hydroxyurea, the drugs are often unavailable in public hospitals. Patients still have to buy it from private outlets,” he says.

Early diagnosis is another challenge. It is critical for managing sickle cell disease, but many patients only seek help when symptoms worsen.

To combat this, Dr Odongo and his team focus on raising awareness through community health promoters, churches, schools, and local barazas.

Stem cell transplant

Another challenge is the high cost of stem cell transplant.

He notes that while stem cell transplants are the definitive treatment for sickle cell, they are neither widely available nor affordable in Kenya. For now, patients rely on a combination of hydroxyurea, folic acid, penicillin B, and regular vaccinations to prevent complications.

"There are trials underway for alternatives to hydroxyurea, but for now, these are the main treatment options."

Despite the challenges, patients like Polycarp — who at 41, has defied the odds — demonstrate that with proper care, Kenyans with sickle cell disease can live long, meaningful lives.

Dr Odongo shares that he has more than 20 patients over 40 years old. "Early diagnosis, proper treatment, and support groups make all the difference," he says.

Dr Odongo emphasizes the importance of adherence to treatment and hydration, while also advocating for moderate physical activity. Common triggers for painful sickle cell crises include infections, dehydration, extreme temperatures, and psychological stress.

"Keeping warm during cold months and drinking plenty of water in hot weather can help avoid crises," says Dr Odongo whose clinic also does genetic counselling to prevent the inheritance of sickle cell disease.

"If carriers know their genetic status, they can make informed decisions when planning a family," Dr Odongo advises. He emphasises the importance of testing for sickle cell traits to break the chain of inheritance.

With 17 counties heavily burdened by the disease, including Kisumu, Busia, and Bungoma, Dr Odongo is hopeful that initiatives like newborn screening will improve the outlook for patients.

However, he urges greater involvement from insurance providers and the government to make care more affordable and accessible.

When it comes to how long someone with sickle cell can live, Dr Odongo says, “you can never approximate the lifespan of an individual. The Almighty God is the one who knows when He will take away your life."