Man or woman? For transgenders, a constant battle to find acceptance

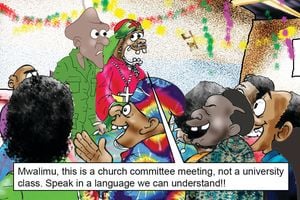

Besides the social stigma that being transgender touches off from the general public in Kenya, there is yet another downside for this group. Experts say that, because transgenders often dislike their genitalia with unreserved intensity, nearly all of them keep away from sexual intercourse. PHOTO | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Gender identity, Dr Mukhwana says, is defined as a personal conception of oneself as male or female. Hence gender identity is a psychological rather than physical issue; and it is self-identified.

- The term “gender identity disorder” is a joint invention by physicians and psychologists to describe people who experience significant emotional and psychological discontent with the sex they were assigned at birth and the gender roles associated with that sex.

- Grown-ups with GID lack self-esteem, are susceptible to abuse drugs and substances, and are generally easily depressed. They also have suicidal tendencies.

One day three years ago, Dominick, a third year student of education at Kenyatta University, took poison in an attempt to commit suicide.

He was rushed to hospital in time, and that made all the difference as doctors were able to save his life.

Dr Philomena Ndambuki, an education psychologist and guidance and counselling specialist at the institution, was part of the team that attended to Dominick that fateful day.

After the physicians were through with administering drugs to the young man, Dr Ndambuki took over. It took a long, friendly talk and many roundabout questions from the psychologist to gain Dominick’s trust, and eventually he calmly told her that there were certain things he liked doing, but those things always earned him ridicule from both his peers and parents.

Dr Ndambuki immediately knew she was on to something, and so she asked Dominick whether he would mind demonstrating the stuff that attracted jibes towards him.

TRENDY URBAN GIRL

He left and came back in the afternoon carrying what looked like a handbag packed with an assortment of items.

He then entered a small room in Dr Ndambuki’s office and a few minutes later, stepped out dressed like a trendy, urban girl, complete with a wig to disguise his shaven head. As happy as a clam, he sat opposite the doctor, ready for their appointed chat.

“I’m feeling perfect,” he beamed.

Dr Ndambuki diagnosed her student as suffering from a Gender Identity Disorder (GID). Put differently, the psychologist established that Dominick was a transgender.

After a good measure of counselling, she divulged her findings and advised Dominick that his condition could be better managed with the involvement of his parents.

When the family arrived later that week, Dr Ndambuki pried into the history of her patient.

She established that throughout his childhood, Dominick had been a “sissy”. He preferred girls’ games and company, and mostly behaved like a girl, to the chagrin of his parents.

“They told me that, although their son was brilliant, he, for some reason, preferred to behave like a girl. He was their only son, born between two girls, and they thought he behaved that way because of the influence of his sisters, and that he would outgrow it when he came of age.”

When she told them that their son was a transgender and it would serve him better to allow him to switch to the gender he preferred, Dominick’s parents did not take it kindly.

Dr Ndambuki, who is also the director of Kenyatta University’s mentoring programme, says “Dominick’s parents went ballistic” when she revealed their son’s diagnosis to them.

READ MALICE

“They read malice in my findings and mistakenly thought I was implying that their son was gay. To them, I appeared more of a problem than their son’s condition. Thus we agreed that Dominick was to continue with his studies as a male, as his parents had raised him.

Luckily, the young man completed his studies without another hitch and I have not heard from him or his family again.”

Such is the challenge that most psychologists in Kenya face when they diagnose a case of transgender. The don says although most Kenyans are not aware, the difference between a gay and transgender is clear.

A gay person, she says, is one who is sexually attracted to, or has a sexual preference for, a person of the same sex. On the other hand, a transgender is a person who, if a man, feels like a woman trapped in a male body, and vice versa.

Dominick is just one among the soaring numbers of transgenders in the country. Hitherto unacknowledged and unheard of, today they are crawling out of the woodwork to demand not only legal recognition of their existence, but space and some specific rights in the society.

Dr Renson Mukhwana, a specialist in children’s development at the Gertrude’s Children’s Hospital in Nairobi, says that, although the terms “sex” and “gender” are often used interchangeably in casual speech, in a medical and technical sense they are not synonyms.

Sex, on the one hand, is defined by the genitalia of the individual, while the term “gender” defines the emotional and bodily processes involved in one’s identity and social role, explains Dr Mukwana.

“Sex is assigned when a child is born, based on the external genital appearance. This is because it is conventionally assumed that genital appearance represents the internal anatomic and future mental status of the newborn. Hence, based on this assumption, a gender of rearing congruent to the chosen sex is also assigned to the baby.”

BIOLOGICAL SEX

Gender identity, Dr Mukhwana says, is defined as a personal conception of oneself as male or female. Hence gender identity is a psychological rather than physical issue; and it is self-identified.

For this reason, gender is defined by one’s own emotional identity as male or female. And this self-identification of one’s gender in one’s mind might not necessarily agree with the biological sex.

For instance, if at birth a baby is assigned the male sex based on its male genitalia and later in life he considers himself a male and comfortably refers to his personal gender in masculine terms, then this person’s gender identity is male.

But if he feels like a female and exhibits typical female characteristics in behaviour, dress and mannerisms, then his gender role is not male. His sex is male but he has assumed a female gender role.

The sex and gender of such a person are incongruous or inconsistent. He is a transgender, stuck in the middle gender that falls between a man and a woman.

Dr Ndambuki says it is estimated that in Kenya, the prevalence of GID in males is one out of every 100,000, and one out of every 130,000 in females.

Because she refers to her encounter with Dominick only to illustrate the drama she had with his parents, Dr Ndambuki does not want to discuss how often she encounters this disorder in her line of work.

“The estimates I have given you are enough. They apply to a generalised sample population in the country. You can extrapolate it to any given cosmopolitan population in any public institution,” she says.

ONLY MEN COME OUT

However, Dr Ndambuki’s estimates do not concur with the gender distribution of people who are currently coming out with GID in the country. All along, only men in Kenya have emerged to own up to being transgenders.

The don concurs with this observation, saying that, because of the premium laid on boys by society, girls with gender identity disorder find it easier to cope with the condition.

In nearly all cases, she says, parents are proud of daughters who behave and feel like men. Their peers also admire them. Thus, in most communities, the disorder in girls is incorrectly seen as socially acceptable, as some sort of asset rather than a liability.

“For the foreseeable future, it is only men who feel like women who will find it tough fitting in, and thus we will see more parents coming out with sons (than girls) who have such disorders,” says Dr Ndambuki.

“Fewer girls and women with GID will be coming out because the symptoms of their condition are acceptable, and because too much is expected of the boy child. Many families, especially in Africa and Asia, become anxious when they do not have a son. Parents will not be bothered if any, or even all, of their daughters behave or even claim to feel like men. They celebrate their daughters who behave like boys. But few can hide their disbelief, disgust, and perhaps utter hatred, for sons who express feelings of being females.”

Besides the social stigma that being transgender touches off from the general public in Kenya, there is yet another downside for this group. Experts say that, because transgenders often dislike their genitalia with unreserved intensity, nearly all of them keep away from sexual intercourse. Their condition makes them asexual or androgynous, almost completely.

“Permanent lack of appetite for sexual intercourse is common among transgenders on both sides,” says Dr Ndambuki. “This is one aspect of GID that mainly exposes transgender females, who are usually assisted by societal pressures to smoothly adjust to their condition.

“As they grow up, it dawns on their parents and society that the woman they have all along admired and praised for living like a man is not taking her romantic gender role as a woman. At this point, depression sets in in the patient.”

PROFESSIONAL CHOICES

Dr Ndambuki says that, besides behaving, dressing and expressing themselves in contrast to the gender they are assigned at birth, transgenders also prefer to take up professions that are conventionally preferred by the other gender.

“It is one thing to have all-male or all-female genitals and quite another to be male, masculine and man or be female, feminine and woman, respectively,” Dr Mukhwana adds.

The term “gender identity disorder” is a joint invention by physicians and psychologists to describe people who experience significant emotional and psychological discontent with the sex they were assigned at birth and the gender roles associated with that sex.

There are also instances in which a child is born with ambiguous genitalia, which is as a result of hormone disorders during development of the foetus inside the womb. In this case, it is difficult to tell whether the infant is male or female by looking at its sexual organs. Such an infant is intersex.

With such complex genital anomalies, assignment of sex of rearing is uncertain at birth. This presents difficult clinical and ethical issues and assignment is usually delayed. When it is eventually done, it might result in GID later in life. In Kenya, there are cases in court by parents of such children.

Gender has several aspects: gender assignment, gender role, gender identity, gender attribution and sexuality. Mostly, gender assignment occurs at birth, marking the beginning of the process of gender socialisation. This process includes society’s expectations of how males or females should behave.

LACK SELF ESTEEM

Gender identity refers to the individual’s perception of his or her own gender and how it conforms with the male or female gender role in society.

Gender attribution is what we generally do when we meet someone and want to determine whether they are a man or a woman. This is often based on traditional cues like clothing, mannerisms, physical appearance, gait, and occupational choice.

Sexuality, on the other hand, refers to erotic desires, sexual practices, or sexual orientation.

Grown-ups with GID lack self-esteem, are susceptible to abuse drugs and substances, and are generally easily depressed. They also have suicidal tendencies. A child with this condition is vulnerable to harassment by his or her peers and is often an anxious, depressed recluse who is socially isolated and lonely.

Experts believe that GID results from biological and socio-cultural influences. It is estimated that 62 per cent of reported GID cases are hereditary. However, medicine and psychology have no evidence of how social and cultural issues might influence the occurrence of GID in people.

Over time, experts have established that, for adolescent or adult patients to be conclusively diagnosed with GID, they must have experienced gender discontent for at least six months. However, there are no criteria for diagnosing the condition in children because they do not know how to express their discontents with their gender.

But they also caution that it is common for school-aged children or teenagers to engage in varying degrees of cross-dressing, sometimes in relation to peer group activity, or for creative expression. This behaviour cannot be equated to gender discontent, unless other specific criteria are met.

Therefore, while most children with gender dysphoria do, in fact, cross-dress, the act of cross-dressing alone does not qualify a patient as gender dysphoric or suggest a specific diagnosis.