Bitter, betrayed but buoyant

What you need to know:

- She may be lonely — even at her advanced age of 81 she still does her own laundry, scrubs the floor of her Nyeri home, and cooks her meals — but she believes there is still hope for her generation

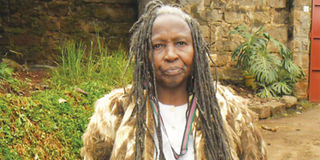

- Muthoni is the only still-surviving female Field Marshal from the emancipation struggle and has kept her dreadlocks to remind her that she is still fighting for a better life for herself and the children of fellow fallen freedom heroes

- Last Saturday during the Mashujaa Day celebrations in Nairobi, Prime Minister Raila Odinga said all freedom heroes and heroines will enjoy free medical care as one way of celebrating their contribution to this state

At her Nyeri home on a cold Saturday morning, Field Marshal Muthoni Kirima casts her piercing, if not unnerving, gaze into the horizon, unable to understand how, just a few days to this year’s Mashujaa Day, she is still the same old woman living through the squalid rhythms of the same old life that has defined her existence for decades.

“Kenya is my only child,” she muses, almost absent-mindedly. The cryptic nature of that statement is embellished by the fact that Muthoni’s marriage did not bear her any children.

She had barely stayed with her husband, General Mutungi, for a year when they joined the Mau Mau freedom struggle in the early 1960s and went their different ways into the forests of Mt Kenya.

Gen Mutungi died in 1965 — two years after the end of the freedom struggle — taking with him to the grave the only hope of Muthoni settling down again to start a family.

“The forest was obviously not the place to bear children,” she explains.

She may be lonely — even at her advanced age of 81 she still does her own laundry, scrubs the floor of her Nyeri home, and cooks her meals — but she believes there is still hope for her generation, hope that, even if they do not join the famous club of liberation heroes and heroines, the story of their struggle will be told and taught to generations to come.

“I am not alone,” she says. “Everybody is my child. But my oldest child is Kirinyaga (Kenya).”

Those words, though, do little to mask the disappointment in the eyes of this lavishly dreadlocked freedom fighter who, like many others of her ilk, have been “forgotten since independence”. Their jobs done, they “no longer seemed an attractive lot” to the establishment.

Muthoni is the only still-surviving female Field Marshal from the emancipation struggle and has kept her dreadlocks to remind her that she is still fighting for a better life for herself and the children of fellow fallen freedom heroes who knew no home except the brutal, dense forests of Mount Kenya and the Aberdares.

“I am still in the forest,” she says, echoing the sentiments of many liberation heroes who have gone before her, and who have variously said the fruits of their struggle and the dreams that sent them to the forests in the first place are yet to materialise.

“Life was hard in the forest,” she remembers. “We survived on herbs and roots. Sometimes we would go for days without food. Most of the time we fed on game meat.”

Whenever they killed an elephant for food, they hid its tusks inside the forest, and by the time the war ended, the jungle around Mt Kenya hid quite a huge fortune.

In 1966, Kenya’s founding president Jomo Kenyatta allowed Muthoni to retrieve the treasure and sell it, and she somehow managed to keep the supply of elephant tusks steady until late in the ‘70s, when the government banned the trade in the wake of a dwindling elephant population in the country.

Muthoni still has a bullet lodged in her hand and, after independence, had to go for a medical operation to save her right eye from the effects of another one that had glazed the protective bone around it during the war.

She and a group of fellow fighters had to be coaxed from the forests though, even after independence. They had somehow got used to the ravages of nature at its best, and she remembers how, one morning, heeding the passionate call of Kenyatta to down their weapons and head to their farms, they converged at Nyeri’s Ruring’u Stadium a weary but battle-hardened lot to surrender their weapons.

“It was on December 16, 1963,” she recalls. “We gathered at the stadium to give up our pistols, guns, machetes, knives, loin clothes... everything. I watched the new Kenyan flag flutter in the skies, and I knew I had accomplished my mission. I had to begin a new life. I had to abandon the bush life and construct my life anew with my already frail husband at Ihururu, Tetu.”

That “reconstruction” of her life with her husband, however, took a brutal turn when the General succumbed to illness two years later. Today, her house on the outskirts of Nyeri Town, next to the famous Outspan Hotel, is adorned with photographs of freedom fighters, her own after independence and Mau Mau memorabilia.

As is the case with other ex-Mau Mau, the field marshal has been demanding recognition from successive governments in vain. There was a ray of hope in 2003 after the lifting of a legal notice that outlawed the Mau Mau movement, which in itself is quite telling given that the freedom army was being decriminalised 40 years after the national independence for which it had selflessly fought.

Muthoni does not have any kind words to describe “the betrayal”. “I emerged from the forest after 11 years but was never given even an inch of land,” she laments. “I have nothing to show for those 11 years, not even a needle. It was only the sons of the supporters of the white men who benefited from the blood and sweat of our battered bodies.”

The former fighter recalls speaking to Mzee Kenyatta about putting up a home for freedom fighters. The old man, she says, seems to have bought into the idea, but it was shoved after it was realised that they could be attacked by the people they had harmed in the quest for freedom.

The Mau Mau administered oaths of loyalty and didn’t hesitate to kill in cases of betrayal, and those opposed to the idea probably felt the anti-Mau Mau brigade may come after them.

Retired president Daniel arap Moi showed some interest in their plight but did little or nothing to help them, says a disillusioned Muthoni. “I dined with the former president, but I never got the assistance I expected. I waited in vain to see how he would help us.”

Except for a medal to mark 20 years of Moi in power in 1998, she has got nothing else to show, as do other Mau Mau veterans.

These days, whenever the aging veteran watches people trooping into stadia during national days, she wonders what the hoopla is all about when the aging freedom fighters who brought such merriment to the land have nobody to champion their plight.

“You cannot shave your nape,” she says, angry and slightly agitated. “There are freedom fighters who, should you tell them there is independence in Kenya, will ask you to clearly and more elaborately define the meaning of that ‘independence’. This is the lot to which I belong, the lot that believes it’s not yet uhuru.”

Muthoni laments that, instead of being treated like heroes, freedom fighters were left to their own devices to die paupers. If it were not for her efforts, she says, she would be living in abject poverty.

After trade in ivory was banned, she started selling fruits and cereals until she accumulated enough money to buy the piece of land on which her home stands.

Although the government has acknowledged that it has not been of much help to the freedom fighters, the Minister of State for National Heritage and Culture, William ole Ntimama, says his ministry has published the National Heroes Bill which will be tabled in Parliament soon. The Bill seeks to establish a legal framework through which all concerns by national heroes will be addressed.

Last Saturday during the Mashujaa Day celebrations in Nairobi, Prime Minister Raila Odinga said all freedom heroes and heroines will enjoy free medical care as one way of celebrating their contribution to this state. “We have directed all government health institutions to offer all our freedom heroes free medical access,” he said.

Should these plans come to pass, the likes of Muthoni would be a happier lot, but she says there is still more that needs to be done to dry the tears of surviving liberation warriors.

At the same Mashujaa Day venue, Vice President Kalonzo Musyoka announced the discovery of freedom hero Dedan Kimathi’s grave inside Kamiti Maximum Prison. “We are now ready to organise a befitting burial (of Dedan Kimathi) once a court order authorising the exhumation (of his remains) is issued,” the VP said.

“We will give (Kimathi) a decent burial once his body is exhumed,” Prime Minister Raila Odinga re-assured the nation.

In the same vein, Field Marshal Muthoni also wants the “protruding bones of fallen heroes in shallow graves in Mt Kenya forests” collected and buried honourably.

“The bones of my fellow freedom fighters are, like me, crying in the forests. We ventured into the forests to free the country from the grip of the White settlers. We thought that those we left behind schooling would fight for us, but things turned out differently”.

Heartache and heartbreak aside, Muthoni remains a respected woman in and outside Nyeri. Through her proceeds from business, she has helped educate children from poorer families, with some proceeding for higher learning overseas.

Now at her sunset years, she hopes the government is listening.