The fight to save Kaptagat Forest: A community's struggle and triumph

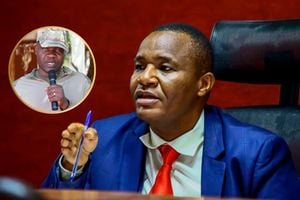

From left: Kaptagat Forest Association Chairman Vincent Chelimo, John Wachira, forester in charge of Kaptagat and Elgeyo Marakwet County Forest Conservator Paul Koech inspect ceder trees planted at Kaptagat Forest on June 28.

What you need to know:

- The once dead wetlands are now teeming with biodiversity.

- Amid bamboo shoots in the wetlands are a well spread beauty of water hyacinth and water lilies. Toads and water beetles jump from leaf to leaf

The expansive Kaptagat Forest, covering over 30,000 hectares in the scenic landscape of Elgeyo-Marakwet County, encompasses five distinct forest blocks — Sabor, Kipkabus, Kessup, Kaptagat, and Benon.

Olympic marathon champion Eliud Kipchoge accompanied by other athletes and officials plants trees at Kaptagat Forest.

Nestled within the Elgeyo Hills Cherangany ecosystem, this vital natural resource holds immense significance for the host and neighbouring counties. Alongside providing a diverse range of wood-based products and serving as a valuable agricultural resource, the forest also boasts state-of-the-art high-altitude training facilities for athletes.

Its lush expanse is home to a rich tapestry of biodiversity, contributing to the region's ecological equilibrium.

Perhaps most notably, Kaptagat Forest is a crucial water catchment area, serving the water needs of approximately seven counties. Its pristine waters quench the thirst of both humans and wildlife, supporting irrigation-fed agriculture throughout Kerio Valley and playing a pivotal role in the cultivation of grain in Uasin Gishu and Trans Nzoia counties, which are renowned as the country's food baskets.

But this fragile ecosystem is now in danger as logging, deforestation, overgrazing, charcoal production, and climate change exert pressure on it. Between the early 2000s and today, at least 35 per cent of the forest has been destroyed, according to the Kenya Forest Service. Vincent Chelim, the chairman of Kaptagat Community Forest Association, has witnessed the forest cover gradually diminish due to human activity. "We were brought up here, lived here and did our farming activities here. As young men, we would graze here. After the lands went bare, we would encroach on the forest some more. We ended up eating into the forest for decades," he says.

"We lost trees, grasslands and wetlands, and now streams and rivers at Kaptagat Forest have started drying up," Paul Kiplagat, the Forest Conservator in Elgeyo-Marakwet, says.

"The community had many user rights back then and these were made without commensurate efforts to restore the forest. Over time, we started seeing significant degradation of this forest. This is where it all began," Dr Chris Kiptoo, the patron of Kaptagat Integrated Conservation Programmes, says.

In the 2000s, renowned environmentalist Wangari Maathai petitioned the Moi regime to evict thousands of people who had encroached on the forest, but her efforts bore no fruit. Three years later, President Mwai Kibaki took over the country's leadership and aggressively evicted forest encroachers across the country, including in Kaptagat Forest. However, as the encroachers left, a big problem was exposed: the destruction of over 30,000 hectares of forest land and the need to rehabilitate the forest. Even though the Kibaki administration managed to evict encroachers from the forest, there was little effort to rebuild the critical ecosystems in the North Rift Region.

But seven years ago, a tide started to change when communities teamed up with environmentalists to develop a systematic approach to restoring the beauty that once was Kaptagat Forest.

The first step was regrowing bamboo trees on wetlands, owing to the tree's versatility in environmental conservation. In total, about 60 per cent of Kaptagat's wetland is progressively being covered with bamboo trees aged between one and five years old.

"The bamboo tree planting is a project that has been ongoing for five years, and one can already see the regrowth of the wetlands that had dried up. All these small streams you are seeing are just coming back to life. Look keenly, and you will see how clean the stream waters are. Our wetlands are slowly taking shape," Mr Kiplagat says.

The transformation is spectacular. The once dead wetlands are now teeming with biodiversity. Amid bamboo shoots in the wetlands are a well spread beauty of water hyacinth and water lilies. Toads and water beetles jump from leaf to leaf.

Indigenous trees, specifically the Lebanese cedar, naturally formed the bulk of Kaptagat Forest in its glory years, so the restoration aims to regrow these species. The community explains why. "Lebanese Cedar trees have become quite rare in Elgeyo-Marakwet County. In this forest, they have been illegally harvested for wood products. My village has taken action to address this issue and restore them. We have planted about 11 hectares of Lebanese Cedar trees inside the forest," explains Kaptagat Forest Association Chairperson Vincent Chelim.

Growing indigenous trees presents a unique challenge compared to cultivating non-native species of trees. Before picking the type of indigenous tree to plant, one has to check for their ecological suitability, seed germination viability, notorious pests and diseases control, and slow growth rate after germination.

"The focus on indigenous trees in the Kaptagat ecosystem is crucial because it serves as a significant water reservoir, providing support to the western parts of Uasin Gishu to Lake Victoria, so restoration will lead to an increase in water supply," Dr Kiptoo says.

"We are growing these cedar trees as a team; we give the host community some land to till in the forest, but there's a catch; the community is also given tree seedlings to plant and tend to the trees' growth as they tend to their crops. The forest becomes the bigger beneficiary, seeing as the community plants, waters and prunes the trees for up to eight years, unlike situations where you plant trees and leave them to grow without close monitoring. This has made the Kaptagat Forest restoration successful, unlike other forest restoration initiatives like Embobut," Mr Chelim explains.

"The ongoing collaboration between the community and the Kenya Forest Services to restore the forest is productive. However, the local community is worried that they may be displaced by the expanding forest in a few years. This concern highlights the urgent need for alternative livelihood options."

It’s against this background that local communities surrounding Kaptagat are being introduced to other sources of livelihood to prepare them for the coming season, where the forest's full cover will displace their forest integration farming, demanding that they stay away from the forest altogether.

Selina Cheruiyot used to grow maize and graze her cattle in Kaptagat to support her family, but after the community was educated about the importance of conserving the forest, she transitioned to avocado farming.

"In 2019, we were given avocado tree seedlings. Avocado farming is a bit more profitable compared to maize farming. I have had two harvests so far, and I am happy. The only challenge I have is controlling pests and diseases," says the mother of five.

Ms Cheruiyot's avocado farm is a fine example of how offering alternative livelihoods can help conserve forests.

"This programme has significantly reduced the societal pressure to encroach on the forest for income. Residents are now benefiting from avocado farming, and issues related to grazing and logging have been effectively resolved in the Sabor block of Kaptagat Forest," Francis Kagongo, who chairs the local Community Forest Association, says.

"Avocado farming has been immensely beneficial; the income is better and I no longer struggle with basic needs, especially food. Further, I can plant potatoes and beans alongside the avocado trees, supplementing my family's food needs," Ms Cheruiyot explains. A few metres from her home lives Truphena Chepseba. She says she has frequented the forest ever since she was a young girl, fetching firewood and burning charcoal, a habit she carried on to adulthood.

When communities in this area began receiving advice to explore alternative energy sources such as biogas, Ms Chepseba initially struggled to fully understand the concept. However, she had no choice but to embrace change due to restrictions on accessing Kaptagat Forest to allow for its regeneration. "Ever since I was introduced to biogas, I haven't had to go to the forest for firewood or charcoal," she says.

Whereas Ms Chepseba would in the past sell charcoal and firewood, she now sells green vegetables to her neighbours.

""After generating biogas, I use the manure to enrich my vegetable garden. Since I no longer have to go to Kaptagat Forest to fetch firewood and charcoal, I have become a mama mboga. I sell indigenous vegetables," she says.

The latest intervention in the efforts to save the forest is the ongoing fencing of the five blocks that make up the forest. However, this move has sparked a quiet conflict between recalcitrant residents and those favouring the fencing. However, stakeholders have called for calm, assuring the community they can still access the forest under regulated conditions.

"There is still a bit of resistance, which I can attribute to a misunderstanding. When the focus is on fencing, people feel like they are being denied entry, which is why the forest department emphasises the need for user rights where community members can sign up to 17 of them. Those who still want some firewood will be allowed to the firewood-zoned areas. Those opting for biogas for their energy needs are doing so voluntarily. After fencing, you will still enjoy user rights; they just need to sign up for them through the Kenya Forest Service," Mr Kiplagat says.