Health ministry urges lawmakers to repeal law criminalising suicide

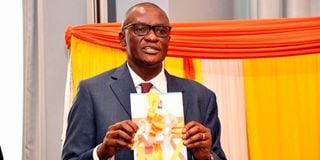

Health acting Director-General for Health Patrick Amoth with a copy of the Suicide Prevention Strategy 2021-2026 which was launched at the Radisson Blu Hotel on August 2, 2022. Kenya has been urged to repeal Section 226 of the penal code that criminalises attempted suicide.

Kenya has been urged to repeal Section 226 of the penal code that criminalises attempted suicide.

Launching the Suicide Prevention Strategy 2021-2026, the Ministry of Health said their goal is to attain a 10 percent reduction in suicide mortality by the end of the year 2026.

“The strategic objectives that will be pursued to achieve the 10 percent reduction include strengthening supportive policy, legal and financing environment [and] advocating for decriminalisation of suicide by repealing Section 226 of the penal code,” the document says.

Speaking at the event, Health Director-General Patrick Amoth described the strategy as a defining moment for Kenya’s mental health services.

Global public health concern

“Suicide, ladies and gentlemen, is a global public health concern, and Kenya is no exception. It knows no boundaries and cuts across every sociodemographic level and in 2018 alone, the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics reported 421 deaths by suicide in the country,” he said.

“The World Health Organisation (WHO) factsheet, 2021, indicates suicide is a leading cause of mortality, and among 15–19-year-olds it remains the fourth leading cause of death.”

He added that globally, about 700,000 people die by suicide every year, with most of the deaths occurring in low and middle-income countries.

He cited WHO estimates that show a suicide rate of 11 in 100,000 people. But he said there is scarcity of data on suicides in Kenya because of underreporting partly influenced by criminalisation of suicide attempts.

No easy task

According to Health CS Mutahi Kagwe, suicide is one of the leading causes of death among young people in many countries including Kenya yet investment in policy and research on prevention is small.

“[Preventing] suicide is complex and while feasible [it is] no easy task,” he said.

“It requires a coordinated multi-sectoral response of the health, education, labour and agricultural sectors, among others, as it is a complex yet preventable public health problem resulting from the interaction of physiological, social, biological and environmental factors.”

New findings by Kemri-Wellcome Trust researchers published in showed that some Kenyans attribute suicide to external forces, which is why many in Mombasa and Kilifi counties seek help from traditional healers and religious leaders instead of going to health centres.

Intervention guidelines

Dr Linnet Ongeri, a psychiatrist and research scientist at Kemri who was the principal investigator and was one of 23 experts who designed the new suicide prevention strategy, explained that understanding how people conceptualise suicides is vital in enabling stakeholders to come up with apt policies and intervention guidelines.

She said some people look at suicides as a taboo subject while others see them as ‘acts of valour’.

“Ninety 90 per cent of people who die by suicide have a diagnosable mental condition, which is why mental health services need to be affordable and accessible while gatekeepers like pastors and traditional healers need to be trained,” she said.

“We cannot neglect them because of our cultural beliefs.”

She explained that most people still find talking about suicide and their own suicidal thoughts uncomfortable, compounding stigma.

“I think to an extent because suicide is criminalised in this country, it adds to the stigma. A number of countries have actually decriminalised suicide because the fear of persecution has an impact on how we view suicides.”

Ms Stephanie Musho, a human rights lawyer, agreed with Dr Ongeri.

Mental health stigma

She said Section 226 of the penal code prescribes “a penalty of up to two years in prison, a fine or both. The phrase 'commit suicide' connotes and perpetuates the stigma around mental health and attempted suicides”.

“This is an outdated law that Kenya inherited from its colonisers. It is redundant, as a government's response to a health crisis should never be punitive. Instead, it should be founded on contemporary and ethical globally acceptable medical standards and guidelines,” Ms Musho said.

She added: “Condemning … patients to prison as opposed to facilitating their treatment goes against the right to health” and Article 25 (a) of the Constitution guarantees “freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

“By subjecting psychiatric patients to jail and denying them the care and treatment they need, the government remains in violation of these constitutional provisions.”