Bandits stoke poverty in Kenya’s most fertile region

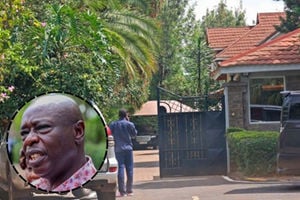

Residents of Arror in Marakwet West, Elgeyo Marakwet County show where one of the cattle rustlers from the neighbouring community hid on January 20, 2022.

What you need to know:

- This is a valley of death, where human life is cheaper than that of a goat. It is a home of scared people losing the zest of longevity; it is a magnet for bandits.

- The sheer disregard for the law is shocking. Where the bandits get the guns is not a mystery, and they have some of the best weapons and ammunition.

- Cattle raids–often fuelled by retrogressive cultural practices–are common. The veneer of civilisation is fragile.

Located in the North Rift is a picturesque land of undulating hills and valleys.

The landscape of Marakwet East can inspire an artist. It looks green and lush, and the residents go about their chores with seeming peace.

But looks can be deceiving. The locals are a scarred lot. They have gone through much, and the depth of their misery is boiling in their innards.

The beauty of the land is deceptive, and the attraction you feel when you reach the place is a misplaced throbbing of the heart.

This is a valley of death, where human life is cheaper than that of a goat. It is a home of scared people losing the zest of longevity; it is a magnet for bandits.

They have raided this place countless times but the attack carried out on January 4 is etched in their memory.

Daring raids

As the scorching sun pierced through the rich red soil of Marakwet East that day, more than 100 armed bandits laid siege on Samar village in the volatile Arror ward.

The men were tilling the land and the women preparing lunch for their children when all hell broke loose.

Gunshots and shrill screams rent the air as the marauding attackers circled the hapless village.

With nowhere to hide, the besieged residents had come face-to-face with the flaming darts of the enemy. Only a few seconds separated life and death.

The anarchy subsided about an hour later and, once the petrified residents could muster the courage to step out of their hideouts, there were two bloodied bodies and several injured men.

And about 1,000 animals had been driven away. It was one of the most daring raids by bandits, widely believed to come from the neighbouring community.

Joseph Kemboi, 47, a battle-hardened elder, spoke to us. Life has engraved a hasty signature on his features; he has aged faster.

Had he not told us his age, we could have easily assumed he was on the wrong side of 70. The very ‘old’ middle-aged man aptly summarises life in this village.

Kemboi beheld the terror visited upon his relations and escaped death by a whisker. He impulsively crawled and hid in a thorny thicket as the attackers marched towards the village.

“They descended on us from all directions at noon. We were caught unawares. They killed two people on this field as I watched. I survived by crawling into a thicket, where I remained quiet. They proceeded to the village and stole more than 600 cattle and 400 goats,” he says, lifting his hand in desperation.

“They moved back to their territory with our animals as we buried the dead. We are farmers and depend on the Chepkum Irrigation Scheme. Sadly, it has become a battlefield due to constant attacks across the border,” he says.

There’s a cold calculus that comes with the way he maps the murders. It’s almost impractical not to be emotionally moved, even for an outsider who lives thousands of miles away in a relatively peaceful environment.

Abandoned scheme

Chepkum is among several multimillion-shilling irrigation schemes abandoned due to perennial insecurity.

The project, funded by the African Development Bank and the national government, provided food security and created employment for hundreds of people engaged in contractual farming.

They grew sorghum, beans, green grams, tomatoes, maize, vegetables, groundnuts, watermelon and cassava. Now that is all gone.

“We are kindly asking the government to come to our rescue. More needs to be done to wipe out banditry and rustling. There will be a food crisis this year because our people were unable to till their farms,” says Kemboi.

Timothy Kiplagat, a farmer at Kabanon Kapkamak Irrigation Scheme in Kerio Valley, Elgeyo Marakwet County on June 29, 2022. A big section of the scheme has been abandoned due to banditry in Kerio Valley, which has adversely affected the economy of the region.

The sheer disregard for the law is shocking. Where the bandits get the guns is not a mystery, and they have some of the best weapons and ammunition.

To them, it seems there is no government at all, and every man does as he pleases.

Cattle raids–often fuelled by retrogressive cultural practices–are common. The veneer of civilisation is fragile.

Underneath every man lurks the animal. Accounts of attackers from the meandering Kobot Hills shooting children going to school are common.

“They (bandits) recently killed a boda boda rider who was just behind me. We live in constant fear. Why is the government not doing enough to stop this? It’s as if we are not part of Kenya,” laments Evans Koskei, 35, a boda boda operator and father of three.

“We have lost many friends, fathers and community leaders. There are more widows and orphans here than in any other part of the country. Is this fair? Don’t we pay taxes? How difficult is it for President Uhuru Kenyatta to issue an executive order to end this mayhem?”

It’s astounding how rampant rustling and its avoidance are woven into the daily fabric of this society.

Some residents are armed and, at times, the only law and order come from your illegally acquired AK-47.

A while back, it had become a warzone and both sides–the armed residents and the bandits–shot each other in the night.

Government intervention

The government had to act; so, it launched an aggressive disarmament drive. That brought some semblance of order to this valley of the shadow of death.

The blunder of the disarmament was that it targeted only the residents with illegally acquired arms; the bandits were nowhere to be found. And the residents were left highly vulnerable to constant attacks.

“The stolen cattle are driven to a slaughterhouse in Mogotio, then onto Kenya Meat Commission. This is done by three groups: The raiders, the transporters and the facilitators,” observes Patrick Tarus, 46, a farmer and father of seven.

Tarus implored Interior Cabinet Secretary Fred Matiang’i to re-arm Kenya Police Reservists (KPR) to deal with the bandits because they know the terrain better than the security officers who have been deployed.

“When KPRs were around, they responded to raids very fast. It was peaceful. The matter was later politicised and it culminated in the disarming of KPRs in 2019. The aggressors were not disarmed,” he recalls.