The lies that bind South Sudanese

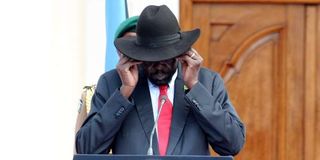

South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- South Sudan’s State House, known locally as J1, is a rather intriguing place, just as it is unnecessarily unfriendly.

- Power is a cruel thing.

- A man can mingle, eat with and laugh with every mortal when seeking power but quickly isolates himself the moment that ultimate goal is achieved.

I have twice accidentally driven into driveways that no man in his right mind would. One was the main entrance to State House in Nairobi and the other was near the back fence of State House on Nakesero Hill in Kampala, Uganda and nearly got shot on both occasions.

Luckily, I was able to persuade the guards to allow me to reverse and be on my way.

Don’t ever make that mistake in Juba. It would not end well for you.

South Sudan’s State House, known locally as J1, is a rather intriguing place, just as it is unnecessarily unfriendly.

Over the years, it has puzzled many curious citizens who want to know what lies inside this tightly guarded compound. After all, anyone passing by it, walking right in front of it or behind it or on the side road next to it, will not fail to notice the tight security, a plethora of armed men congregating at the entrance, supposedly watching out for anyone with ill intentions for the hatted man seated inside.

And yet, as the passersby also see a traffic of pedestrians entering and exiting, some in uniform, some in suits, some women in flip-flops and others in rags or clutching children in their arms and seeking to enter the coveted J1, they may be fooled to think that they too have their citizenship right to enter.

Some of them, mostly women, congregate across the road, hoping to see one of the gatekeepers to power. But through all the beehive of people, someone could get attacked, injured or killed for seeking access.

POWER IS CRUEL

Power is a cruel thing. A man can mingle, eat with and laugh with every mortal when seeking power but quickly isolates himself the moment that ultimate goal is achieved.

No citizen is too naïve to realize that this is the republican palace, the symbol of power hierarchy, of male power, the pinnacle of class structure, the abot of those who eat on our behalf.

As such, for those wanting to look inside J1 or those seeking financial assistance in times of distress such as during the Covid-19 pandemic, as millions of citizens down on their luck are wont to do, looking around J1 or hanging out near it is tantamount to asking for a bloody nose.

But that is us, South Sudanese. We are new to the fault lines that divide wealth, power, big man syndrome, stars on the shoulders and class snobbery from poverty, from our carefree attitude, our natural born conviction that anyone of us can be president. For were we not just on the same level as recent as 15 years ago when we were all faced with the realities of liberation?

And so, J1 and any other temple to the god of power, are not out of reach for any mortal.

Many of these mortals wish to know if the place is open and accessible to ordinary citizens and what it takes for such access to be attained. Some wonder if this is the place where all their wants and needs would be answered if they got an opportunity to set foot inside.

Some wish to see the inside just so they can find out what the place that they think consumes all their money looks like on the inside. Others wonder if the President sleeps in J1, how his children and his entire family live. Are they modest, lavish, hardworking or spoon-fed?

In any case, the amount of curiosity on the outside of the J1 fence is limitless. In this war-torn, impoverished, politically in disarray, ethnically divided and supposedly oil rich country, how can we not be curious to look?

People want to know what has become of the country that was born of war, made possible by the death of 2.5 million people and which was celebrated by the whole world when it finally became independent.

Before it became South Sudan, it was one of the most oppressed and destroyed territories on earth, perhaps only second to Europe during the Nazi onslaught.

Before it became a country, this territory had gone through a long history of slavery, Arab racism, Islamist oppression and suffered homegrown and in-ward violence, triggered by competition between “liberators,” over power they did not yet have.

Some liberators attacked their own and then ran to Khartoum, into the arms of the government they had fought to replace.

FEUDS

More violence was brought on by feuds over resources along ethnic lines and some was brought on by the stresses of life under oppression. Some was brought on by militarist ethos of liberation of the past 40 years, where women were expected to contribute to the liberation, if not by combat then by their wombs, to birth the nation that was being decimated by the liberation effort.

But compelling women to be revolutionaries through reproduction became a licence for violence against them. Such prolonged violence leaves a taxing legacy that is not easy to shake off.

It is this history of violence that had deprived so many of resources, of decent living, such that when a new dawn,independence, was only just on the horizon, the politically and militarily powerful but weak at heart trembled at the sight of the plum.

The State was automatically up for grabs and its public resources viewed by the unscrupulous as private.

Such were the makings of the mess that is now South Sudan, and the private citizen has her eyes fixed on State House, for where else is the conductor of this train wreck seated?

One person asked me once if I knew whether the man with the black cowboy hat, gifted to him by President George W Bush of the United States, ever takes a moment to look outside his fortress. Just to remind himself what it was that took him to war all the years of his youth, the idea that he was liberating masses of oppressed South Sudanese, liberating them from entrenched slavery and systemic racism by northern Sudanese, impact of colonialism, from hunger, disease and lack of education.

It would seem that the man with the black cowboy hat would be very keen and interested to know how the people he helped liberate were now living, what his soldiers now ate, how their kids were fairing in terms of nutrition, vaccination, education, how the ordinary men and women who essentially paid the cost of liberation war were now enjoying the independent status of their country.

SIGNIFICANT DAY

It is July 30, 2020 as I write, a very significant day in South Sudan’s struggles to be free. It is the day the founding leader of the liberation movement, John Garang de Mabior, died in plane crash exactly 30 days after he had just started to implement the peace agreement that brought the freedom war to a close.

It is exactly 15 years ago to date when he died in mysterious circumstances that have left the South Sudanese mourning and with no answers as to what took their beloved leader.

It is now the day all the martyrs are remembered. But the children, the widows of these martyrs can only look with longing eyes into J1 from outside its fence.

The seat of power seems to have forgotten them entirely.

Now, the current leadership of South Sudan avoids to face the millions of families that offered their young recruits, offered their resources to feed fighters, sacrificed their own well-being just so that South Sudan is realized. But to what end?

The author is a professor of anthropology at Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University.