Unravelling the life of Philip Ochieng, the grand old Kenyan media maverick

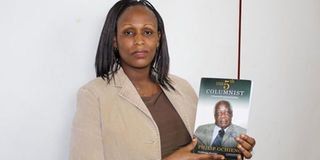

Kenyans are bound to have sharp opinions on him. So, there will be admirers and haters of Liz Gitonga-Wanjohi’s biography of Ochieng, The 5th Columnist: A Legendary Journalist (Longhorn, 2015). This book is a remarkable attempt to get to know Philip Ochieng and to tell the world about this eccentric man. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- Wanjohi shows us Ochieng’s early life — a rural life, in a polygamous home; a life built around European-introduced religion, education, administration, economy and social changes that extremely remake Ochieng’s community; a life from which a brilliant young man is set to depart, into unknown lands of Alliance, Nairobi and America.

- Ochieng is presented as naturally intelligent, topping his classmates at primary school until he arrives at Alliance, where he meets more gifted students. Probably because he was upstaged by cleverer students or for being away from home, Wanjohi writes that records show Ochieng having “difficult years at Alliance”.

- Then there is the Ochieng who goes to America in the same period as Barack Obama Snr to study but never gets a degree. The author writes: “He never completed his BA degree at Roosevelt University. In fact, out of the nearly 1,000 students who left the country between 1959 and the mid-1960s, he is the only one who never completed his studies.

- Yet Ochieng stands accused, by many Kenyans, of several ills that he allegedly committed as a journalist. He is accused of having used his time as the editor-in-chief of the Kenya Times to harangue those opposed to the government of the day.

How does one tell the story of a person variously described as proud, bigoted, eccentric, conservative, and a show-off?

Mention Mr Philip Ochieng’s name and Kenyans are bound to have sharp opinions on him. So, there will be admirers and haters of Liz Gitonga-Wanjohi’s biography of Ochieng, The 5th Columnist: A Legendary Journalist (Longhorn, 2015). This book is a remarkable attempt to get to know Philip Ochieng and to tell the world about this eccentric man.

Undoubtedly, love and hate will resonate through the reactions to the biography. Some readers will praise Mrs Wanjohi for the effort to illuminate the elusive life of Ochieng. Others will find ammunition to shoot more at Ochieng for sins he supposedly committed against them. Maybe those in the middle will see this book for what it is, a disinterested but critical inquiry into the life of Ochieng, but which in the end is really also an insider’s history of Kenyan journalism.

There are several versions of Ochieng that you will meet in The 5th Columnist. According to Wanjohi, there is the boy from Awendo born to Nicanor Otani and Stella Pesa, on September 17, 1938. Ochieng was one of 10 siblings by different mothers. He went to a local school, Manyatta Primary, established by the Seventh Day Adventists, till Class Four, when he moved to Lwala Primary School, a government school for Class Five. He then joined Pe Hill, a Church Missionary Society (CMS) school, for Class Six to Eight, from where he was admitted to Alliance High School. From Alliance, Ochieng travelled to America in 1959, as part of the first group of the American Airlift organised by Tom Mboya and others.

PAINTING CHICAGO RED

Author and journalist Liz Gitonga-Wanjohi with a copy of her book, The Fifth Columnist: A biography of Philip Ochieng. PHOTO | COURTESY

So, Wanjohi shows us Ochieng’s early life — a rural life, in a polygamous home; a life built around European-introduced religion, education, administration, economy and social changes that extremely remake Ochieng’s community; a life from which a brilliant young man is set to depart, into unknown lands of Alliance, Nairobi and America.

Ochieng is presented as naturally intelligent, topping his classmates at primary school until he arrives at Alliance, where he meets more gifted students. Probably because he was upstaged by cleverer students or for being away from home, Wanjohi writes that records show Ochieng having “difficult years at Alliance”. But the young man manages, under the watchful eye of the famous Carey Francis, to leave Alliance honourably. He got a Division One.

Then there is the Ochieng who goes to America in the same period as Barack Obama Snr to study but never gets a degree. The author writes: “He never completed his BA degree at Roosevelt University. In fact, out of the nearly 1,000 students who left the country between 1959 and the mid-1960s, he is the only one who never completed his studies.” Instead, Ochieng, with his friends, “… painted the town red … drunk all the beers in Chicago”. Although he had a wife, Nova Diane, and a child, Juliette Akinyi, Ochieng abandoned the family in the US and returned to Kenya after finding life difficult.

Remember Barack Obama Snr doing the same to his young family? Was this a case of free spirited individuals; men who wouldn’t be pinned down by societal expectations; individuals who always followed their hearts rather than their heads?

It is this seeming relentless pursuit of his choices that have made Ochieng an East Africa legend in the world of journalism. From America, Ochieng came back to Nairobi and didn’t stay for long before he left for France, to study again. But even the philosophy and literature he read in France didn’t hold him down long enough to earn the paper qualifications. According to the author, Ochieng flew back to Kenya on the night of December 12, 1963, to join other Kenyans in ushering in their independence. He then worked as an untrained teacher at Homa Bay High School, got married to Jennifer Dawa, joined the ministry of External Affairs and later resigned to work as a reporter for the Nation newspaper in 1966.

REBUKING TANZANIANS

If controversy is what you are looking for, then the author of The 5th Columnist offers you a breathtaking journey through Ochieng’s life as a journalist. From the Nation, Ochieng went to Tanzania in 1970 after being asked to resign from Nation for having burnt some overly inquisitive female journalist’s nose with a cigarette. Life in Tanzania proved quite enjoyable, where Ochieng met several world scholars such as Walter Rodney, Ayi Kwei Armah, Mohammed Issa Shivji and African leaders, including Robert Mugabe, Sam Nujoma, Yoweri Museveni and Agostinho Neto.

But Ochieng had to leave Tanzania, claiming that Tanzanians were fed up with his presence. He had rubbed some Tanzanians the wrong way with his columns, ‘The Way I See It’ and ‘Ochieng on Sunday.’ Tanzanians couldn’t just stand a man who rebuked them for their failings, in English, a language few of them were good at because of their colonial heritage.

From Tanzania, Ochieng worked for the Weekly Review then Target — a Nairobi-based Christian weekly, before he rejoined the Nation after a stint in exile and some time in Dar again. He resigned from Nation in December 1981 when he was the chief sub-editor and left for Uganda in 1982. His stay there was short-lived.

Ochieng’s paper published a story citing then President of Seychelles, Albert René, accusing Charles Njonjo of being involved in the attempted coup in Seychelles. Some people in Obote’s government weren’t happy. It was exile again, in Italy, where he worked for Inter Press Service for three years before returning to the Nation, resigning in 1988 to edit the Kenya Times, the ruling party, Kanu, newspaper.

It is his time at the Kenya Times that many Kenyans associate with Ochieng more than when he worked elsewhere.

Ochieng may have been the co-author of the most memorable book on Kenya’s political transition, The Kenyatta Succession, with Joseph Karimi. But probably his enduring contribution to knowledge on Kenya’s media is his book, I Accuse the Press.

Yet Ochieng stands accused, by many Kenyans, of several ills that he allegedly committed as a journalist. He is accused of having used his time as the editor-in-chief of the Kenya Times to harangue those opposed to the government of the day.

He is accused of rejecting multiparty democracy. Many condemn him for personally attacking individuals through the pages of the Kenya Times. Others believe to date that Ochieng was behind the infamous character assassinating ‘Kanu Briefs’ that ran in the Kenya Times in the 1990s.

SEA OF SORROW

But Ochieng defends himself stridently in The 5th Columnist, insisting that he wasn’t at the Kenya Times when the ‘Kanu Briefs’ were published. He blames Amboka Andere, the editor who succeeded him, for having authorised the publication of the libelous articles.

Ochieng remains convinced that his reasons for rejecting multiparty democracy have been vindicated. According to Mrs Wanjohi, Ochieng believes that the democracy Kenyans clamoured for and have today has ethnically balkanised the country, as he had predicted.

Was he a mouthpiece for Kanu? The author quotes him saying that he was expressing what he believed in and he wasn’t the kind of man to receive instructions from President Moi or the party stalwarts to write on their behalf.

What you get from Wanjohi’s picture of Ochieng is a complicated sketch. Here is a man who would abandon his family for years whilst in exile and come back to his wife and children. His wife is presented as a resilient woman who believed that in the end Ochieng would go back to her.

Ochieng confesses his sins, such as when he attacked the Kikuyu community for leading the opposition to Moi and Kanu in the Kenya Times and abandoning his American family, but he always offers an explanation for his actions.

For some, this attitude may appear to confirm the views of those who feel that he is rude, arrogant and self-obsessed. But for others, he may just be a man unwilling to drown in the sea of regret and sorrow. In any case, there are few Kenyans who escaped the supposed smelly brush of Kanu; and you got to give it to a man who is well read and demonstrates knowledge in his arguments given the vacuity of ken one encounters in debates in Kenya.

Despite its downsides, including missing articles, commas and a bewildering chapter “Why Ochieng is not rich,” Liz Gitonga-Wanjohi does an inspiring job in The 5th Columnist of laying bare significant layers of Ochieng’s public and private images.

There are anecdotes in plenty — of refusing to follow Luo traditions, marrying a second wife brought home by his wife, whisky drinking, shouting at colleagues, never having learnt to drive a car, never wearing a watch, etc — to shock and mesmerise — but in the end one sees a man who has fairly enjoyed his life. Yet there is still that pesky feeling that Ochieng may have to publish his own book for Kenyans to know more about why he lived such a nomadic life as a journalist.