Azimio la Umoja - One Kenya Coalition leader Raila Odinga at public gathering at Kamukunji Grounds in Nairobi on December 7, 2022.

| Dennis Onsongo | Nation Media GroupWeekly Review

Premium

Raila, the ‘unwanted’ exile

What you need to know:

- Western governments were afraid of antagonising the ‘friendly’ Danial arap Moi government.

- Uganda under President Yoweri Museveni was keen to avoid a diplomatic dispute with its neighbour.

Recently declassified documents in London have for the first time revealed the full extent of efforts by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) to secure safe passage for opposition leader Raila Odinga, who had fled to Uganda on October 26, 1991 fearing for his life, and the reluctance of big Western powers to give him political asylum.

Mr Odinga, a serial political detainee who was at the time a leading campaigner for multiparty democracy and prominent opponent of President Daniel Moi’s autocratic regime, had crossed into Uganda through Lake Victoria disguised in religious gab. With rumours spreading about his whereabouts, a Ugandan government official hurriedly convened a press conference and confirmed to reporters that

Mr Odinga was indeed in Uganda, but his request for asylum had been rejected.

The government of President Yoweri Museveni, well aware of the annoyance Mr Odinga’s presence in Kampala would cause the Moi administration and possibly result in a diplomatic row, reacted swiftly by passing him on to the UNHCR.

According to the British government documents, on October 28, 1991, just two days after Mr Odinga’s arrival in Kampala ,the UNHCR representative, only referred to as Mr Farah, requested an urgent meeting with the British High Commissioner to Uganda Charles Cullimore.

According to the British government documents, on October 28, 1991, just two days after Mr Odinga’s arrival in Kampala ,the UNHCR representative, only referred to as Mr Farah, requested an urgent meeting with the British High Commissioner to Uganda Charles Cullimore.

“Farah , the UNHCR representative, called to see me this afternoon at his urgent request accompanied by his assistant,” Mr Cullimore wrote in a priority telegram.

During the meeting, Farah informed Mr Cullimore in strict confidence that before fleeing Kenya Mr Odinga had made asylum enquiries with American and German diplomats in Nairobi. The UNHCR representative further revealed to the British High Commissioner that Mr Odinga’s first option was Germany, which they were “pursuing vigorously”.

Farah’s aim was to put Mr Odinga on a flight to Brussels, Belgium, the following day, after which he would board a connecting flight to Germany. But the plan was being delayed by the Germans indecisiveness on the asylum request.

Even though a similar request had been made to Norway and the United States, Farah sought to know from Mr Cullimore whether the UK would be willing to take in Mr Odinga incase other options failed.

The British High Commissioner, while assuring Farah that he would pass on the request to London, urged him to continue pursuing the Germany route. He further pointed out that he was not aware of any willingness by Her Majesty’s Government and the High Commission in Nairobi to assist Mr Odinga with his asylum case.

The meeting ended with Farah promising to update the High Commissioner about any development.

Following the meeting, the diplomat telegrammed London, seeking advice on how to respond to the request. The telegram marked “confidential” was also copied to the British Embassy in Bonn, Germany.

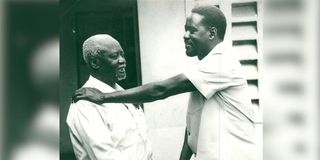

Father and son seem lost for words at their first meeting at the elder Odinga’s Bondo home since his son Raila was detained five years ago. But Raila’s arm, and the look in their eyes express all the emotions of the moment. Raila travelled to Bondo soon after his release from detention.

“As things stand there is no need to respond further to the approach Farah has so far made. However, it would be helpful to have instructions on how we should respond if the German option falls through and Farah returns to us,” he wrote.

He was however of the opinion that one way or another, Mr Odinga should be out of Uganda as soon as possible since it was “ important in terms of bilateral relations between Uganda and Kenya”.

It was clear from the records that the British and Americans were hesitant to offer Mr Odinga asylum.

This could be explained in the context of Cold War, which was at its tail end. The Odingas and other political agitators were considered a threat to Western interests by antagonising Moi, who was seen as a safe pair of hands,.

In one file marked “confidential”, covering the 1980s and early 1990s, Koigi wa Wamwere and Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o were described as “enemies of Kenya” who should not be given a safe landing in Britain.

In fact, Prof Thiong’o only got his indefinite leave to remain in Britain after an immigration officer made a mistake and endorsed his passport, the documents reveal.

The Foreign Office was so much angered by the error that it wrote a protest letter to the Home Office stating: “We are very concerned at the proposal that the error in Ngugi’s Ghanaian passport should in effect be legitimised . Ngugi is the enemy of Kenya number one. I am also disturbed by the fact that Ngugi appears to have two passports, one Ghanaian and the other Kenyan. We also seem to be having problems keeping a track of Ngugi’s movement (Something we had agreed we should do), can things be tightened up?”

Such was the dilemma of many of those who fled to the West during that period. Nonetheless, Mr Odinga was eventually offered asylum in Norway where he remained for a couple of months.

Birds of a feather? FORD Kenya’s Raila Odinga (left) listens to Koigi wa Wamwere at the All Saints Cathedral where they met for the Release Political Prisoners Cultural Week.

While he was away freezing in the biting Norwegian winter, back home Moi, had yielded ground following persistent pressure and announced the return of multiparty politics in December 1991. With the clamour for change at its peak, Mr Odinga was not ready to remain in exile for long. He was particularly keen on attending the first rally of the newly formed political party — Forum for Restoration of Democracy (Ford) — which was to be held at Kamukunji. The only problem was that he didn’t have a Kenyan passport and his Norwegian one was not valid for travel to Kenya.

To navigate this logistical challenge, according to the declassified documents, he approached Lord David Steel, a former leader of the British Liberal Democratic Party, to intercede for him so that he could get his passport back. Lord Steel, who later served as the presiding officer of the Scottish Parliament, had spent part of his boyhood in Kenya.

Lord Steel’s father, the Rev David Steel, was the minister of St Andrews Church Nairobi in 1949, and was known for his criticism of colonialism in Kenya. This put him at odds with the Governor of Kenya and some of his congregants.

Just like his father, Lord Steel was an acclaimed campaigner for social equality. “I have been conscious from my earliest days.

There are interrelations between one’s personal belief and attitude to social questions.” Perhaps this explains his early association with liberation figures and movements in Africa.

In 2007, for example, he backed Mr Odinga’s bid for the Presidency, stating that the opposition politician and his father Jaramogi Oginga Odinga “have always been guided by a moral code whose cornerstones are truth, nationalism, democracy and social justice. Driven by powerful consciences, both men always remained true to the cause of justice for all and freedom from tyranny”.

The British Conservative magazine, Spectator, in its January 2008 issue, stated: “It is a little known fact that though Raila Odinga was a socialist firebrand who named his son Fidel Castro, his mentor was the former Liberal Party leader Lord Steel.”

It is therefore not surprising that Mr Odinga chose to approach him in 1992 to help him get his Kenyan passport back. Following the request, Lord Steel raised the issue with an official of the East African Department (EAD) in the Foreign Office, who then informed the British High Commissioner in Nairobi: “Sir David Steel has been approached by Raila Odinga who is now living in Norway about the possibility of getting his passport back.”

The official went on to say that he had intended to raise the matter with Dr Sally Kosgei, the Kenyan High Commissioner to the UK , but was not able to secure an appointment because the Kenyan diplomat was operating between Nairobi and London.

“I wanted to make clear to her that I was not lobbying on Raila Odinga’s behalf as such but rather concerned with the level playing field aspects of the pre-electoral situation.”

In concluding his telegram, the official requested the British High Commissioner, “ if you are seeing Kosgei could you perhaps feed this in and let me know what reaction you get”.

The following day, the official sent another telegram to the High Commissioner in Nairobi asking him to do everything possible to talk to the Kenyan government about Mr Odinga’s passport.

“Raila Odinga is due in London on 20 January for a meeting with Sir David Steel. Apparently, the FORD meeting in Nairobi has been put off in the hope that Raila Odinga will be able to be there, but it cannot be put off much beyond the last few days of January,” he wrote. “Grateful therefore anything you can do to secure an early indication of the Kenyan authority’s likely response to a request from Raila Odinga to have his passport back.” He also sought to know whether Mr Odinga would be harassed by the police in case he returned.

The High Commissioner responded the following day, promising to raise the matter with Kenya’s Minister for Foreign Affairs Wilson Ndolo Ayah. “I am seeing the Foreign Minister this afternoon and will mention Raila’s case to him.”

But he also expressed his frustration on why he should be the one pursuing the issue of Mr Odinga’s security with the Kenyan government.

“Other opposition figures have been able to return to Nairobi without suffering police attention or being refused admittance. If Raila Odinga wants to know whether this will apply to him also , surely he has only to ask the Kenyan authorities himself,” he complained.

Chief Inspector Ikonya of the Nairobi Central Police Station, Nairobi, explains to members and suporters of the Release Political Prisoners pressure group, who included FORD Kenya’s Langata MP Raila Odinga (left) why they were not allowed to plant trees at Freedom Corner to commemorate Political Prisoners Day. Others were Murugi Kariuki, Victor Wachira, Kang’ethe Mungai, Karimi Nduthu, Kitur arap Tirop, Geoffrey Kuria Kariuki, Rumba Kinuthia, Labour Democratic Party chairman Noor Mohamed and physician Lukas Munyua.

Mr Odinga eventually returned to Kenya on January 28, 1992 after around two months in exile. A document detailing his return indicates he arrived at the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in the morning. And at around 10am, he telephoned the Deputy British High Commissioner to inform him that he had not been harassed or hindered by the authorities at the airport.

“He was grateful for the concern shown by the minister and Tom Harris,” read a telegram sent to London following the telephone conversation.

That same year, he contested and won the Lang’ata parliamentary seat in Kenya’s first multiparty elections, marking his debut in elective politics.

The writer is a London-based Kenyan researcher and journalist