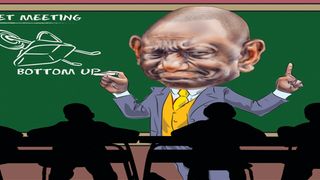

On May 23, President Willaim Ruto took it as his personal responsibility to educate his legislators on the finer details of the Finance Bill and other sensitive budgetary and policy proposals that are facing strong headwinds.

| Illustration by @NyagahWeekly Review

Premium

Hustlers and Bustlers: The full-time politics job of William Ruto

If there are a few factors that define President William Ruto’s leadership style beyond aggressive consolidation of power, they are his hands-on approach, close attention to detail and mastery of the policy platforms on which he was elected.

On May 23, his social media propagandist and nominee for Cabinet Administrative Secretary in the Ministry of Information, Communications and the Digital Community, Dennis Itumbi, came out with a revealing post on Twitter:

“The Parliamentary Group Meeting at State House is literally a classroom. MPs, Woman Reps, Senators, found notes, pens and notebooks, and from 8am, it has been a proper classroom on Finance Bill, Housing, Health and Government plan. The first class was taught by President @WilliamsRuto”.

That is a president who takes it as his personal responsibility to educate his legislators on the finer details of the Finance Bill and other sensitive budgetary and policy proposals that are facing strong headwinds.

Previous presidents would also have hosted Members of the National Assembly and the Senate to impress on them the importance of uniting behind the government when the Bills came to the vote in Parliament, but it would more likely have been about using the bully pulpit to whip them into line, rather than an educational session.

Apart from Ruto himself, Principal Secretaries and government technocrats spent the day at State House taking the MPs through the finer aspects of taxation, petroleum pricing, the controversial housing development levy, universal health care and other policy proposals.

The intention was to rebut the fierce public criticism around what is seen as over-taxation and policies that hit the poor, which might have even Kenya Kwanza MPs wary of backing unpopular measures.

But there can be no doubt that even as he employs education and persuasion to get his troops into line, Ruto will also have his whip very much at the ready with the clear message that any MP who defies the party line will face consequences.

That is the Ruto who oozes charm but takes no prisoners in what are clear efforts since taking office last September to consolidate power by neutralising the opposition while also ensuring strict discipline within his own ranks.

Ruto might sometimes feel like a control freak, but the same week also showed that he is secure and confident enough to delegate power, including allowing Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua to chair Cabinet meetings.

A day before the State House tutorial, Gachagua had come out with his own Tweet: “Reviewing progress of implementation of The Plan. Today, I chaired a Committee of the whole cabinet, the first, at the DP official residence in Karen, Nairobi. The Ruto Administration is on track in rebuilding our Nation. Mbele iko sawa”.

That might seem like a routine assignment, but since independence, all Presidents have jealously guarded their prerogative on the chairing of cabinet meetings.

A ‘committee of the whole’ cabinet as that chaired by Gachagua last Monday is a cabinet meeting in all but name, which is very distinct from smaller cabinet sub-committees that may occasionally be chaired by the Deputy President, Prime Cabinet Secretary Musalia Mudavadi or any other minister as assigned.

In allowing his deputy to chair a Cabinet meeting, President Ruto might well be borrowing a leaf from his predecessor, Uhuru Kenyatta.

Development programmes

In 2019, Kenyatta signed an Executive Order giving his Cabinet Secretary for Interior, Fred Matiang’i, authority to chair a key cabinet committee on the implementation of development programmes, whose membership included all cabinet secretaries, the Attorney-General and the Head of the Public Service.

Retired President Uhuru Kenyatta, former Interior CS Fred Matiang'i and former PM Raila Odinga in a past event.

That was essentially the full cabinet, elevating Matiang’i to the level of a de facto Prime Minister in all but name, and earning him the moniker ‘Super CS’. It was also the appointment that marked Uhuru’s formal sidelining of Ruto, his then Deputy President who had thitherto chaired various cabinet sub-committees on delivery of development programmes, but was now left with no specific functions.

Apart from stripping Ruto of responsibilities, Uhuru’s vote of confidence in Matiang’i was also seen in a way to reflect his own laid-back nature and distaste for details and hard work. Uhuru essentially handed over most of his core responsibilities to Matiang’i, and a tradition established since independence of the President chairing cabinet meetings at least once a week, every Thursday, was abandoned.

The cabinet under Uhuru from then on met only sporadically, mainly to ratify decisions reached under Matiangi’s stewardship.

If that arrangement was an example of the President ceding key day-to-day functions of office so that he could retreat to a life of leisure and relaxation, it also marks a key difference between President Uhuru and President Ruto.

When the latter started his insurgency while still serving as Deputy President, his minions were dispatched on the campaign trail to hit out at the President as lazy, disengaged and a bit too distracted by drink.

That contrasted with depiction of Ruto as hard-working, energetic, sober and in touch with the common man. It was also what gave rise to the hustler vs dynasty campaign theme, with Ruto portrayed as the son of peasants who reached the top through sheer hard work and Uhuru as the spoilt privileged scion of First President Jomo Kenyatta, who let others do the heavy lifting as everything was handed to him on a silver platter.

A look at the Ruto Presidency and his leadership style invariably must bring comparisons between the two men, who came into office tied at the hip. The ‘UhuRuto’ package was elected in 2013 radiating youthful energy and enthusiasm.

Kenya's fourth president Uhuru Kenyatta receives a sword as a symbol of authority from his predecessor Mwai Kibaki (left) during his inauguration at the Moi International Sports Center Kasarani in Nairobi on April 9, 2013.

The dynamic – or digital – duo caught the public imagination with their first cabinet announcement when they appeared

dressed in identical fashion: rolled up sleeves and no jackets or ties, signalling a break from the stolid old ways of doing things.

Uhuru elected President at 52 and Ruto his deputy at 47 indeed marked a generational change as President Mwai Kibaki left office at the age of 82 (having been elected in 2002 aged 71).

But even as they trumpeted youthful dynamism, Uhuru and Ruto were as different as can be on account of different upbringings and approaches to life.

Uhuru had always been the relaxed, fun-loving ‘royal’ who had been dragged into the family business, politics, almost reluctantly.

Steely determination

He could show steely determination and a ruthless streak when need be, as with running two successful presidential campaigns, but he often gave the impression that he’d much rather be engaged in more leisurely pursuits than the hurly-burly of politics.

If Uhuru at some point was the party animal, Ruto was, from the word go, the political animal. For him politics is not a distraction but a full-time occupation around which everything else revolves, including business and religion.

In that regard, Ruto is probably more like one of his mentors, former President Daniel arap Moi.

Like Moi, who succeeded Jomo Kenyatta in 1978 and reigned a record 24 years till 2002, Ruto proclaims a deep Christian faith and is a teetotaller, renowned for being extremely hard-working and a stickler for discipline and time-keeping.

Ruto, like Moi, is known for moderation, keeping a healthy lifestyle, but even going the extra mile with asceticism, including strict diets evidenced by the recent weight-loss that has spawned rumours of ill-health.

A strict personal regimen that reportedly includes cycles of fasting should keep Ruto trim and fit well into his Presidency, in contrast to Uhuru, who came into office impressively lean but had developed an expanded waistline and puffy circles around his eyes by the time of departure.

Like Moi, Ruto, despite his frugal ways, is also one of the sharpest dressers around, displaying a penchant for tailor-made designer suits complemented by top labels in shoes, watches and other accessories.

The self-proclaimed hustler’s enjoyment of the finer things in life apparently does not distract him from the business of leadership. In terms of pursuing his agenda, Ruto leaves nothing to chance as demonstrated with the State House tutorial.

The hands-on approach is also evident with the manner in which, from the start, he moved to consolidate his position by aggressively poaching elected leaders from Raila Odinga’s Azimio la Umoja coalition, therefore securing crucial majorities in both the National Assembly and the Senate.

Well aware of the frailties that plagued previous ruling movements – including his own Jubilee union with Uhuru between 2013 and 2022, President Kibaki’s NARC between 2002 and 2007 and the Grand Coalition government from 2008 to 2013 – Ruto set out to build for his 2022 bid a political vehicle he fully controlled.

Initially, he ruled out a coalition arrangement, insisting that anyone supporting his presidential campaign fold their own parties and join his United Democratic Alliance.

Most of the small one-man outfits complied, but Ruto, the pragmatist, had to relax his stance in order to bring on board the western Kenya regional formation, Musalia Mudavadi’s ANC and Moses Wetangula’s Ford Kenya, that could secure electoral victory.

ANC party leader Musalia Mudavadi (left) and Ford Kenya boss Moses Wetang'ula. They were promised 30 percent of government by Ruto.

That kind of alliance-building was no different than that displayed by all his four predecessors.

Jubilee was a union of his then URP and Uhuru’s TNA. When Ruto fell out with Uhuru, he saw the President get into bed with erstwhile rival Raila to keep him in check. Kibaki had his grand coalition with Raila to secure the peace following the 2007 post-electoral violence, and before that the union with Raila that secured victory in 2002.

There was also Moi’s short-lived alliance with Raila after the 1997 elections. And in the period leading to Independence, the senior Kenyatta had teamed up with Oginga Odinga, Raila’s father, under the Kanu banner to fend off Moi’s and Ronald Ngala’s Kadu.

Jomo fell out with Odinga

Then, as Jomo fell out with Odinga in 1966, he brought in Kadu, with Moi as Vice-President, to help him keep a newly-minted opposition at bay.

Top: ODM leader Raila Odinga and President Uhuru Kenyatta. Bottom: The then Vice-President Oginga Odinga (left) with President Jomo Kenyatta in the early 1960s.

That is the kind of alliance-building common in Kenya, where political parties are just temporary vehicles for acquisition of power rather than movements bound by any ideological platforms.

Ruto’s UDA, and the wider Kenya Kwanza coalition, has tried to sell the Hustler Nation and the Bottom Up economic strategy as an ideology or guiding philosophy.

However, the challenge in coming years will be retaining a unified front as the Mudavadi-Wetangula grouping moves to counter Gachagua’s central Kenya formation ahead of a succession tussle sure to start being played out at the re-election campaigns for 2027.

In the meantime, Ruto still has to fend off the threat posed by Raila, whose on-off, on-again street protests are proving a real distraction at a time he is buffeted on all sides by an economy in turmoil and growing public disenchantment.

Apart from often acknowledging Moi as his political mentor, Ruto has pointed to Kibaki as the President he would like to emulate. That can only be in relation to the manner in which the Third President swiftly revived the economy from the destruction of the Moi era, rather than chaotic political leadership and responsibility for the 2007-2008 post-election violence.

A former Finance minister, Kibaki came into office with a stellar reputation as a very sharp economist. He managed to steady the ship and launch impressive social and infrastructure programmes despite diminished capacity following a road accident just before the 2002 elections and a stroke soon after taking office.

With all his mastery of facts and figures around the Kenya Kwanza agenda, however, Ruto has not been able to replicate what might be termed the Kibaki miracle. Even with the debt hole inherited from Uhuru’s Jubilee administration – glossing over the fact he served as Deputy President for the ten years – taken into account, the Ruto administration has been unable to display a clear grasp of what it will take to stop further slide into threat of default.

Instead, it seems to have invested everything into pushing questionable and unpopular policies such as the housing programme it is unable to sell to the citizenry, even if MPs might be persuaded.

Ruto has also been distracted by politics, moving to shore up his power base with manoeuvers more reminiscent of Moi than Kibaki. Eventually, he will have to decide which of the two men he will want to be remembered for learning from.