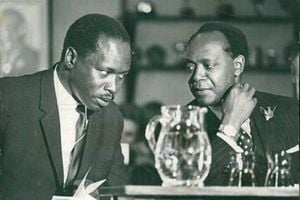

Former President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

Having recently celebrated my 95th birthday, and with my memory still intact, I am keen to record some remarkable events during my two decades in the Kenyan Civil Service from 1947 in this series for the Weekly Review. In this fourth instalment, I recall my interactions with the last colonial District Commissioner of Turkana, Leslie Whitehouse, who watched over Jomo Kenyatta in detention — but became the founding President’s friend and was later appointed a magistrate after independence in a strange twist. Plus how I got a permit for my girlfriend to visit “closed” Northern Frontier District

Some Weekly Review readers may well wonder why I am writing about the last colonial District Commissioner of Turkana. Let me explain – Leslie Whitehouse was no ordinary administrator. At one time, he was in charge of Jomo Kenyatta who was held in detention at Lodwar. Many years later, he was to become a close friend of Kenya’s first President who, remembering how well he had been treated while his liberty was curtailed, rewarded this DC in more ways than one as you will learn from this article.

Leslie Whitehouse (popularly known as ‘Wouse’), was one of those rare breed of Englishmen I’ve ever met and under whom I was privileged to work with during my early career in the colonial Kenya Civil Service in Turkana. Whitehouse was a man with a purpose — be it in Maasailand where he worked as a teacher or in the sweltering heat of Turkana where he was DC for many years.

From the time he landed in Turkana in 1947, he told me his main concern was the welfare of the people at a time when other officers were more keen on promotions and the long breaks in England.

When he was ‘forced’ to take overseas leave because of the regulations obtaining at the time, he insisted on being posted back to Turkana on his return. For officers at the Secretariat, who arranged postings of officers, this is just what they wanted since not many an administrative officer, having served the required term in what was then classed as an “unhealthy station,” wanted to return there.

Whitehouse was a self-educated man with not much formal academic qualifications to his name but one who could well outshine his colleagues when it came to dedication to duty.

In Turkana, Whitehouse was highly respected and also feared by his immediate officers and the locals. Despite this seemingly harsh exterior, he was a fair-minded individual who respected the views and opinions of others. I got on very well with him and to prove this point let me narrate an incident that I have never forgotten.

As some of you may know, women from outside the region were prohibited from entering this so-called “closed district” at the time unless they were given special permits. I, on the other hand, was keen that my girlfriend who worked in Kitale, and her entire family be allowed to visit me in Turkana.

It is necessary to explain that anyone entering the “closed” vast part for Kenya that was then referred to as the Northern Frontier District, and which included Turkana, had to first obtain a “permit to enter.” It was effectively a passport that was not given freely.

So how did I convince this tough administrator to make a concession in my case? I had to get him in a good mood and when the opportunity arose, I mentioned this to him while we met socially for drinks at his house. I was dumbfounded when he agreed and lost no time in preparing the official Pass allowing my visitors entry into Turkana.

On returning home after that social evening, I could hardly believe my eyes but was worried he might change his mind! To my delight I found he had signed the Pass without comment so I lost no time in sending the Pass down to my girlfriend in Kitale asking her to see that they were all ready to undertake this arduous journey by traders’ lorry!

I am delighted to report that not only did the entire family consisting, among others, of six females (some no doubt children) arrive in Turkana by official government transport, but the DC went out of his way to grant me unofficial leave to take the entire family to Fergusson’s Gulf on Lake Turkana (then referred to as Lake Rudolf) where we spent two lovely nights by the lakeshore catching tilapia and generally enjoying the break.

Whitehouse was a stickler for perfection and would not suffer fools gladly. He was also keen to ensure that his junior officers didn’t take advantage of his administrative staff by getting them to undertake chores which were personal. He was very fair in dealing with us, the clerical staff, and always made sure that we were given time off to get down to Lake Turkana or “down country” to Kitale.

Although Whitehouse had a fiery temper – and some people always put this down to the intolerable heat of Lodwar — he was a gentleman.

It was during the period when the Mau Mau movement was active that several prominent political leaders, among them Jomo Kenyatta, were detained here at Lodwar and the sub-station of Lokitaung.

Whitehouse now had a new political prisoner to take charge of. It is heartening to report that both prisoner and DC hit it off very well, so much so that when Kenya attained independence Jomo Kenyatta, not forgetting how well he was treated, rewarded the colonial administrator on his retirement as DC. The founding President not only ensured that Whitehouse was well cared for but also appointed him as Resident Magistrate in Kitale – a post he held for many years until his death in 1989.

Because of his desire to remain in the country, Whitehouse had become a Kenya citizen. Despite his loyal and dedicated service to the colonial administration over many years, he did not qualify for a retirement pension from the British government, or the supplementary awards that retired officers were entitled to since he had changed citizenship. This must have hurt him immensely, especially since his many written appeals to the British government and even one to Her Majesty the Queen, were turned down. Here was a man who had given almost his entire life in the service of the colonial government and was now being disowned by it!

By contrast, the independent Kenya government never forgot him – they made sure he was well cared for in retirement and had hoped that he would continue as Resident Magistrate in Kitale for many years to come.

English writer Elspeth Huxley said Whitehouse “was treated with atrocious meanness by the British government” but “considerably generously by Kenya's First President, Jomo Kenyatta, and then by President

Daniel arap Moi.”

Whitehouse led a simple life. Even in retirement he was frugal thinking more of others. He had no attachment to material things— in fact the Christian agnostic left everything he possessed to the Catholic Mission in Turkana.

Towards the end, he became dependent on others, was wheelchair bound and unlike his previous alert attitude, became very confused. The end came when he slipped away quietly on October 2, 1989. At his own request, the funeral was arranged by his Catholic friends. He is buried in Kitale cemetery.