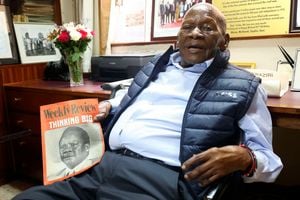

In his heyday, former Cabinet minister Maina Wanjigi was synonymous with Kamukunji Constituency.

In his heyday, Maina Wanjigi was synonymous with Kamukunji Constituency, where he had succeeded the slain Tom Mboya – the larger-than-life politico whose assassination changed Kenyan politics.

When he lived, Wanjigi, an agricultural economist, straddled the spaces he occupied like a colossus. He never shied from saying what he thought and always meant what he said.

In politics, he paid that as a little price. Many sang songs about him. The Nyakinyua Dancers in his constituency composed various songs in his honour and would invoke his name easily.

As Kamukunji residents later found, his words were his bond. Those who knew him say he spoke his heart with unbelievable honesty. It is no wonder he titled his biography “The Shepherd Boy in Search of Virtue.” History, as archival records show, has been kind to him.

Born in Fort Hall (later Murang’a District), Wanjigi, who died on Thursday at the age of 92, was educated at Kagumo High School, where his classmates included Jeremiah Kiereini, who would later become a powerful figure in the Kenyatta and Moi presidency.

Studying at a time when Africans were being discouraged from pursuing university degrees, Wanjigi joined Makerere University where he attained a diploma in agriculture.

He was later encouraged by Dr Julius Gikonyo Kiano, Kenya’s first PhD, to apply for a university degree.

Subsequently, Wanjigi followed Dr Kiano’s advise and was admitted to join University of Connecticut for a B.Sc. degree in Agriculture where he graduated with top honours.

As a result, Wanjigi was offered a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship to study at Stanford University for an MSC in Applied Agricultural Economics.

While at Stanford, he worked with the World Trade Institute before returning to Kenya in 1961, where the colonial government said he was “overqualified.” Thus, there was no job for him at the Ministry of Agriculture, then controlled by White settlers.

Wanjigi opted for a low-paying job as an agricultural officer in Nyeri—though he was much more learned than his supervisors. Independence found Wanjigi being wasted with mediocre colonial positions that did not fit his education.

But at 36, in June 1965, Kenyatta appointed him as Kenya’s Director of Settlement, a position that saw him oversee the implementation of postcolonial land policy.

It was here that Wanjigi would be tested by the Kenyatta-era barons who wanted to take over the White Highlands for themselves.

Stop allocating land

Wanjigi features prominently in the settlement records, where he advised his superiors on the need to settle the landless and stop allocating land to the powerful within the government. This is his legacy within the settlement department.

When Kenyatta started implementing the Z Plot Scheme, in which senior cabinet ministers and top government officials were being allocated 100 acres, Wanjigi protested at the new arrangement, which he said was “inconsistent” with the financial agreements. Wanjigi then realised that he was on his own.

On July 29, 1965, Wanjigi wrote to his PS, Peter Shiyukah, stating his position – or perhaps to have a record in place: “Until this matter is cleared with the lenders, I am afraid that we have got to discontinue any more approvals for 100-acre plots.”

Wanjigi’s suggestion was shot down by Shiyukah, who, apparently, was one of the beneficiaries of the Z-plot scheme. Many others thought the same.

It appears that Wanjigi was keen to create new spaces of integrity in the settlement schemes where corruption, nepotism, and tribalism had emerged.

By then, Wanjigi was concerned that after borrowing money from the World Bank and Commonwealth Development Corporation (CDC), government officials were no longer settling the landless but allocating land to kith and kin – or to themselves.

In his letter to Wanjigi, Shiyukah said: “I confirm once more that if the decision of suspending the allocation of 100 acre plots is implemented, it would be met with a lot of opposition from the president, ministers and public at large. I agree that as a first step we should have asked permission from the World Bank and CDC to make alterations in our agreements with them. While we are negotiating with them it is not necessary to halt our practice of allocating 100-acre plots since we are too advanced in it.”

By invoking Kenyatta’s name, Shiyukah had silenced Wanjigi. How he felt is unclear, but he has helped historians of Kenya’s postcolonial settlements.

Maina’s documents and letters allow us to navigate the intricate details and politics surrounding the Z plots. For instance, he was the one who compiled the entire dossier containing the names of all those who got 100 acres plus a house and read who is whom in the Kenyatta government.

The list was demanded by the Minister for Lands and Settlement, Jackson Angaine, to determine those who had yet to be allocated land.

In one of his letters to Wanjigi, after Daniel arap Moi applied to get Gunson’s House within the Perkera Scheme in Eldama Ravine, Angaine instructed Wanjigi to “demarcate 100 acres to make the house more attractive.” This was the practice then.

However, he did not stay for long at the ministry. He was appointed as the executive director of ICDC, and his task was to assure investors that Kenya would not nationalise the commercial and industrial sectors outright but would continue to steer the country with “limited nationalisation”.

Wanjigi replaced Joe Wanjui, who had joined East African Industries (EAI) in ICDC. Though he only stayed for a short time within ICDC, Wanjigi was credited with laying a framework that Africanised commerce.

As MP Ojwang O’Ombudo once remarked in Parliament, “Those were hard times because we did not have enough funds, but great efforts were made by Wanjigi, a determined man.”

Wanjigi resigned his ICDC position in 1969, after Mboya’s death, and was elected MP for Kamukunji. Between 1969 and 1992, Wanjigi represented the constituency apart for five years between 1979 and 1983, when he was defeated by Philip Gor.

In politics, Wanjigi identified with the proletariat. For instance, in 1972, when the City Council started a major crackdown on barbers who eked their living on the roadsides, Wanjigi took them to Kenyatta’s Gatundu home, organised as the Outdoor Barbers Group of the African Barbers Association.

Kenyatta was said to have directed her daughter, then-Mayor Margaret Kenyatta, to stop any further crackdown on barbers. Asians mainly ran barber shops in the early 1970s, while most African barbers operated in the streets.

He would also encourage his constituents, mainly from Muranga villages, to trade in second-hand clothes, thus populating the Gikomba markets with his supporters.

Election petition

After succeeding Mboya, Wanjigi was appointed an assistant minister for Agriculture and held this position until 1979, when he lost his Kamukunji seat to Philip Gor. While Wanjigi believed that he had been rigged, his election petition was thrown out.

It was during this period that he concentrated on building his business empire. Wanjigi would later regain his seat after the Charles Njonjo traitor saga, which saw Moi dissolve Parliament in 1983.

After his victory, Wanjigi was appointed to various dockets as minister for Tourism, Environment, Public Works, Natural Resources, Cooperative Development, and Marketing.

As Minister for Public Works, he championed the preference of local contractors in government tenders. In 1985, President Moi tasked Wanjigi with devising a framework for examining the unemployment crisis in Kenya.

The Wanjigi Report led to the adoption of the Sessional Paper on Unemployment, which is cited widely in academic circles.

This report endorsed the Mackay Report, which recommended the 8-4-4 education system and the creation of a second public university.

The Wanjigi Report further emphasised practical skill development and argued that the academic-oriented education system significantly contributed to unemployment. At one point, Wanjigi was one of the few Murang’a elites Moi wanted to rely on as a counterbalance to historical Kiambu dominance.

The others were Dr Julius Gikonyo Kiano, Joseph Kamotho, and Charles Rubia. But the dalliance would lead to a fallout. When Dr Kiano and Wanjigi lost their seats in 1979, Moi appointed them to lucrative parastatals. Dr Kiano was appointed chairman of the IDB, while Wanjigi became chairman of Kenya Airways.

Development” oriented leader

In Nairobi politics, Wanjigi would entrench himself – and showcase his stand as a “development” oriented leader. The Maina Wanjigi Secondary School, long before the Constituencies Development Fund was in place, is one of his signature projects started from scratch in Eastleigh.

In May 1990, when the Nairobi City Commission under Fred Gumo demolished the Muoroto slum near Machakos Country Bus Station, Wanjigi openly protested the killing of seven people.

Wanjigi was then sacked as a Cabinet minister and dismissed by the Nyayo regime crusaders as a “tribalist.” Within this period, he was driven out of Kanu into political oblivion.

Though Wanjigi was not in the ranks of the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD), he would later emerge as a voice of reason as he defected to the party. But the return of Keneth Matiba and his decision to vie for presidency left Wanjigi politically torn.

He decamped to Charles Rubia’s Kenya National Congress (KNC) but was defeated as Matiba re-organised Nairobi politics.

Early in his entrepreneurial journey, Wanjigi teamed up with Matiba, and they had shareholdings in Carbacide before they badly fell out.

As Matiba attempted to place his son Raymond and finance advisor David Kabeberi as Carbacide directors, the other shareholders stopped him. He was eventually thrown out of the board, leaving only Wanjigi and Robert Shephard.

Behind him, Wanjigi has left a solid business empire under the Kwacha Group of Companies, including the Kitamaiyu Coffee Estate, established by colonial lawyer Kenneth Archer in 1919.

Wanjigi was many things – a politician, an investor, and a farmer. His son, Jimi Wanjigi, appears to be taking over from him, but the shepherd boy goes with his legacy intact.