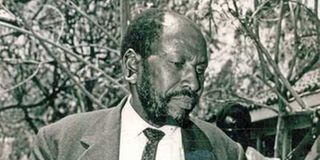

Freedom fighter and businessman Kung’u Karumba.

This month, the family of veteran freedom fighter and businessman Kung’u Karumba will, perhaps, silently mark 50 years since his mysterious disappearance in Uganda in 1974. The story of Karumba, last seen alive on Saturday June 15, 1974, is the larger story of regional politics and business in the volatile 70s – and the risks that entrepreneurs faced as democratic spaces shrunk – as the East African Community (EAC) faced its major political test.

As an entrepreneur transversing the imagined borders, Karumba waded into the lawless Uganda, where President Idi Amin’s military rule had brought the ‘Pearl of Africa’ to a standstill as military and special branch officers abandoned the law and became the law.

Accompanied by his 19-year-old son Peter Karanja, the former Kapenguria-Six member had left Nairobi in his brand-new Toyota Hilux, KPW 301, for a business and debt collection trip as his Kenyan transport empire grew westward. Karumba was to be hosted in Bugembe, near Jinja town, by an acquaintance, Ibrahim Mungai, and his wife, Susan Wamaitha, an indicator of how local connections were mobilised to grow trade in the region.

By relying on Wamaitha as his debt collector, Karumba was not only building trade networks for himself but also showing how social networks were critical in driving the spirit of the East African Community and future integration.

What Karumba did not know was that the social networks he had established in Uganda had fallen victim to Amin’s politics. If he had known that this would be his last business trip, he would have skipped this debt collection trip.

Cross-border trade

The cross-border trade, just like the EAC, was pegged on trust – but Karumba had a stubborn customer, Margaret, who was said to be a mistress to a military office. This relationship helps us to understand how women traders navigated the regional space and exercised power within the context of Amin’s notoriety.

The story goes that that evening, Wamaitha advised Karumba to report Margaret to the police, hoping that the police would have the audacity to confront the mistress of a military office. But that is not how power was exercised in Uganda, and this was a failure on the side of Wamaitha and the illiterate Karumba on the paths to cross and the walls to jump.

That morning, Karumba confronted Margaret, who contacted her military boyfriend. Karumba is said to have invoked his relationship with President Jomo Kenyatta and suggested that he would call the Kenyan president – who at the time was not on good terms with Amin. Such bravado was dangerous, but it was Karumba’s only defence mechanism, or he naively misunderstood the Cold War era political scene he was operating in.

A year earlier, the US Ambassador to Uganda, Thomas P. Melady, had described Amin’s regime in a telegraph message as “racist, erratic, brutal, inept, bellicose, irrational, ridiculous, militaristic, and, above all, xenophobic.” “General Amin has jumped and shifted in so many different, often contradictory, directions during the past year that most observers of the Ugandan scene have long since given up trying to predict what his next move will be,” he wrote.

Volatile space

Karumba was caught up in this volatile space, the right man at the wrong time. As one of the Kapenguria Six, the Kenya African Union (KAU) leaders who had been arrested on the dawn of the 1952 State of Emergency and jailed in Lokitaung after they were convicted over their links with Mau Mau freedom fighters, Karumba was well-known during the pre-independence period.

Thus, his disappearance, which coincided with the 1974 fallout between Idi Amin and Kenyatta over Amin’s unpredictability, was big news in the region. Besides Karumba, many other Kenyans had started disappearing in Uganda as Amin sought to sabotage the East African Community and create his own version of Uganda nationalism.

In August 1972, Amin gave the Ugandan Asians 90 days to leave the country, triggering an exodus of businessmen who had become the fulcrum of Uganda’s growth. The Asians’ exit had left a void filled in by indigenous African businessmen such as Karumba.

Born in 1902 in Limuru’s Tigoni village, Karumba had turned into business early on. By 1952, he had bought three buses that plied Nairobi, Eldoret, and Kisumu routes. He was one of the most prominent African business gurus by local standards. He combined this with KAU politics, and like Njenga Karume – who had followed a similar path – his wealth shielded his illiteracy and allowed him to hobnob with the KAU intelligentsia. The Corfield Report on Mau Mau claimed that Kenyatta forced the Limuru KAU branch to accept Karumba’s leadership. When they refused, a parallel organisation led by Karumba was formed.

In 1964, after independence, Karumba had hoped that Kenyatta would appoint him as a District Commissioner. But Kenyatta had realised that Karumba was not literate. He challenged him to continue doing business but had her daughter employed at State House. Kenyatta would later use Karumba’s success to ridicule Kenya People’s Union politico Bildad Kaggia, who was wallowing in poverty as a leftist after he refused to participate in the land grab.

Colonial bigwigs

In Kiambu, Karumba had organised peasants from Karai Village to form the Karai Farmers Cooperative Society, which in 1970 purchased a 2,400-acre farm in Nyahururu. This land was later shared by society members who named the place “Gwa Kungu” [Kungu’s Place] as an honour to him. Today, Nyahururu Gwa Kungu is a bustling shopping centre. Those who knew him say that Kungu was by 1970 an entrepreneur per excellence. He had buses and lorries plying from Mombasa to Malaba, Nairobi-Namanga and the Nairobi-Moyale route styled as Kungu Karumba & Co. Limited.

Despite this wealth, Karumba was still living in Kariakor and had not joined the trail of wealthy Africans now occupying the affluent spaces left vacant by colonial bigwigs. Karumba’s disappearance forced Kenyatta to contact Idi Amin, an indicator of how personal relations played out. On June 30, following the Karumba outcry, Amin established a Commission of Inquiry led by Justice Mohamed Saied to investigate “the Disappearances of People in Uganda since January 25, 1971, and “whether there are any individuals or organisations of persons whether within or outside Uganda who are criminally responsible for the disappearances or deaths of the missing persons”. Whether this was to appease Kenyatta was unknown – or as part of Amin’s cover-up strategy is not known. The Commission was also to advise Idi Amin on “what do to put an end to the criminal disappearances of people in Uganda”.

The Commission was certainly a mockery. Though given the mandate to meet privately, Amin also decreed that no evidence touching on “security of state” shall be heard. More so, he directed that the enquiry shall not extend “to persons of Asian origin or extraction who though claiming to be citizens of Uganda either remaining outside Uganda or at any time ran away from Uganda for any reason”.

Military police

Interestingly, the US Embassy in Kampala interpreted Amin’s move as “a genuine attempt to improve internal security.” In a memo sent to Washington, the Embassy said: “How urgent it is to have something done has once again been made clear by the recent disappearance of Kungu Karumba, a former ally of Kenyatta’s who was on a business trip in Uganda.”

The Embassy argued that Amin “wants a point of leverage to limit the power of certain persons in the Special Branch (secret service), in the public service unit, or in the military police, since he is no longer as dependent on them as he once was”.

Karumba was not the only Kenyan who had disappeared. Kenyans living in Uganda had gone through hell under a restless Amin. In early February 1973, Amin’s soldiers grabbed 40 Kenyans who were working with East African Railways Corporation at gunpoint. They were never seen again.

On July 7, 1976, Permanent Secretary Geoffrey Kariithi wrote a note to Anthony D. Marshall, US Ambassador to Kenya, telling him that “Amin’s men killed Kungu Karumba.” He also said that “throughout 1974, Ugandan tribesmen with the support of the Amin’s regime continued to harass our citizens along the common border.” This note was written when Amin threatened to annex part of Kenya. Karumba’s body was never found – and it is believed that Idi Amin’s murderer-in-chief Maliya Mungu, was involved in either the disappearance or the actual killing. Details have not been forthcoming. Some 50 years later, Karumba’s death is one of Kenya’s mysteries. All we know is that a man just vanished.