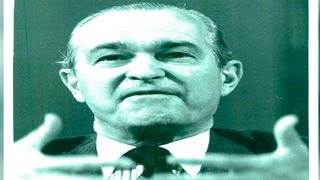

Former CIA Director Richard Helms testifying before a US Senate Committee in 1978. In the small world of the CIA, there is a good deal of gossip amongst case officers and wives.

| File | Nation Media GroupWeekly Review

Premium

CIA, prostitutes, crocodiles and other African espionage stories

Now that the Russians seem to be entrenching themselves in Africa and seeking validation of their politics with grains, fertiliser, and freebies – let me tell you some of the Cold War stories I recently glanced at from some CIA archives that touch on Nairobi.

In 1976, John Stockwell, who was based in Nairobi at one point, became the most senior official CIA official to spill the beans about their operations in Africa.

After he wrote the tell-it-all book, In Search of Enemies, mainly on his escapades in Angola, the CIA went to court and stopped him from getting royalties and telling stories about other stations.

One of the fascinating stories that Stockwell told during his book promotion tours is how he was assigned to go to New York and Florida to recruit prostitutes who could be sent to East Africa to be used against Soviet, Chinese, and North Korean ambassadors to gain intelligence about them or from them. If possible, to blackmail them. The espionage space is perhaps the most thrilling.

Described as a “tall, steady, broad-shouldered man with striking physical presence”, the University of Texas alumnus had started working at a car dealership in Denver after graduation when the CIA letter came.

They asked whether they could do a background check with the possibility of hiring him. He agreed – and, to cut the story short, he was hired.

Lure foreign diplomats

After Stockwell was sent to Kenya in his early years, he was introduced to the “special access agent” programme in 1972. In this programme, women operatives would be used to lure foreign diplomats into bed to obtain secrets. “It was a pointless operation,” Stockwell told Reuters.

In one of the talks he later gave at Vassar College in 1983, Stockwell said he and another agent obtained from the White House Office of the Secret Service the name of one “high-level call girl” whose clients included governors and senators. He ended up with the girl, as he later admitted.

“She was introduced to me by the White House Secret Service, a brilliant, warm person who was available when governors and visiting chiefs of state came to town, demanding sex.

She loved the idea of doing her thing for national security and working with her, she and I became deeply involved, which was inevitable, stupid, and complicated things immensely.”

There are no details about that girl, but he goes on: “I found yet another, a nurse, whom I sent to the overseas post and whom we succeeded in getting to bed with a target official in a resort.

She returned a report that he was an alcoholic, which we already knew, because we had chatted with him at sufficient cocktail parties, that he had halitosis, which we also knew via the same assessment technique, and that he was impotent, which we also knew because we had a camera hidden in the wall of a certain flophouse.”

He posed to Reuters: “But what kind of operation can you generate against such a man who’s willing to park his official Soviet embassy vehicle in front of a whorehouse?” More details of the operation, which “cost the American taxpayers $28,000”, are contained in Stockwell’s book, The Praetorian Guard – though he doesn’t name the country.

According to Stockwell, the Russian diplomat did not meet the woman again – and soon, it was Stockwell who would suffer.

“In the small world of the CIA, there is a good deal of gossip amongst case officers and wives. Disenchanted with what she was hearing about my activities in the world of prostitution, my wife soon sued for divorce.”

After the divorce, Stockwell left for Vietnam where, as he says, he would later become part of the CIA officers freeing the fall of Saigon in 1975.

CIA escapades

Another story that recently fascinated me from CIA escapades in East Africa was on the search for a poisonous viscera of a crocodile’s gall bladder. This story first appeared in the Seattle Times in February 1979 and was filed by Rick Anderson.

The CIA also archived it. The story was based on documents obtained by the Citizens Commission on Human Rights under the Freedom of Information Act, which were made public.

From the records, the CIA had the Tanganyika Crocodile (gall bladder) Plan, a 23-year-long CIA project that was terminated in 1973. According to the exposé filed by Daniel Gilmore, the plan was to capture an African crocodile “with the help of a witch doctor’s secret recipe, cooking the animals gall bladder up into a special poison”. It is not clear what the CIA wanted with this poison or who were the targets.

Details on the crocodile project were contained in a 363-page dossier, and one of the quoted memos states: “We have approached the problem of picking up a Tanganyika crocodile’s gall bladder from two points of view.

The first is to have one of our (reducted) buddies in Tanganyika find, capture, and eviscerate a native crocodile on the spot and then try to ship its gall bladder and – or other poisonous viscera to the United States. The second alternative would be to acquire a crocodile through a licensed collector and ship the live animal to the United States.”

It was reported that there were two contacts in Tanzania, and according to the memo writer, “they can provide us with details concerning methods and techniques employed by the witch doctor in preparing the poison”. They were also to collect “more data concerning other natural poisons derived from other reptiles and or vital organs”.

The memo warned that there would be custom problems “if shipping a live crocodile were ruled out and it was decided to send only a gall bladder”. “One of the main difficulties of getting the gall bladder and or other vital organs to the United States is that the shipment must proceed through British-controlled Kenya.”

Another journalist, Rick Anderson, wrote in the Seattle Times in June 1979 and described the Tanganyika Crocodile Plan as part of a “mind-altering drugs” project and that “testing was nonetheless performed, sometimes diabolically, on unsuspecting Americans; at times, even on some of the CIA’s own agents”.

Anderson wrote his story after reviewing the documents made available to the Citizens Commission on Human Rights.

Perhaps the most exciting thing is that the Soviets would later use this information in their propaganda. A CIA Office of Research document, “Soviet Propaganda Alert No April 6 April 26, 1982,” noted the Soviet’s continued “attacks on the US for alleged past and present use of CBW (chemical/biological warfare) in many parts of the world – including Vietnam, Pakistan, Afghanistan – have increased in frequency.”

For instance, the CIA complained about a 1982 article by Iona Adronov in the Literaturnaia Gazeta which accused the US of searching the world for exotic poisons to use on various peoples and individuals.”

Some of the allegations quoted by the CIA were “the gall bladder of a crocodile from Tanganyika; “Chondrodendrom Toxicoferum’ from the Amazon Jungle and Oyster toxin from Alaska… the obvious intent of all these charges, besides diverting attention from Soviet use of chemical weapons, is to sway the world public opinion against the United States and to drive wedges between the US and its European partners.”

Another story told elsewhere was that of a CIA field station secretary, a twenty-something young girl who fell in love with a communist, resigned, and married him.

“The security implications for the station and its agents were mind-boggling. There were agents who would have been in danger if exposed; she knew them all: their names, how much they were paid, where they met the case officers.”

All the personnel in the unnamed African CIA station had to be redeployed. And what we learn from these stories is that we should always look at the bigger picture.

[email protected] @johnkamau1