Breaking News: Ruto orders postponement of school reopening

News

Premium

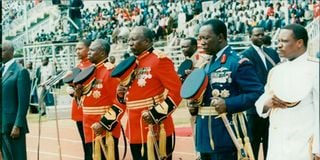

Lt Gen Nick Leshan: The man who flew 1982 Coup plotters to Tanzania

When he died on Friday last week, Lt Gen Nick Leshan went with the full story on what he knew about the abortive August 1, 1982 coup plot.

Was he part of the plot, as the Tanzanian court ruled, or was he kidnapped to fly out the coup leaders as held by the Kenyan government?

While most of the implicated senior Kenya Air Force officers, including Maj Gen Peter Mwagiru Kariuki, were either dismissed or jailed, Leshan survived within the ranks and retired as a lieutenant-general.

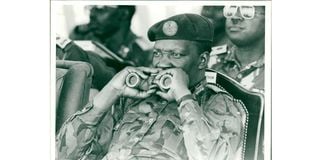

It all started on the early morning of August 1, 1982 when servicemen from the Eastleigh air base led by Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka managed to seize key installations in Nairobi and announced that they had toppled Daniel arap Moi’s government.

But hours later, the army, led by Maj Gen Mahmoud Mohamed, managed to suppress the mutiny as the ring leaders— Snr Pvt Ochuka and Sgt Pancras Oteyo Okumu escaped to the Eastleigh air base, hoping to either stage a fight or escape.

At around 11am, according to Leshan, he was seized from his house at the air base by Snr Pvt Ochuka and made to lie on his stomach near the operation’s centre, where Ochuka addressed some servicemen and urged them to fight.

Together, on the ground, were Col (Ronald) Kiluta who later became an MP, a Maj Mbaka, a Lt Odhiambo and Maj William Jack Marende – the pilot who would join Leshan in the escape to Tanzania.

Shortly after, according to Leshan, he was forced into a saloon car, an Alfasud, together with Marende and driven towards the Buffalo 210 aircraft.

“Do not be surprised to find Col Kiluta dead,” Ochuka said as they entered the car. At the back seat was Oteyo, armed with a sub-machine gun.

“Immediately after I locked the aircraft, I heard Maj Marende receiving instructions from Snr Pvt Ochuka to fly to Tanzania,” Leshan would later tell the court.

The problem was that he had no maps and no assistants and thus had to fly blindly.

A Buffalo plane required at least three people to fly - a captain, a co-pilot and a navigator.

Leshan found that his co-pilot, Maj Marende, was of little use since he was only experienced in flying “small training planes.”

He could only help in stabilising the plane during after take-off.

He would later say that five miles into the Tanzanian airspace, and while flying low to avoid radar detection, a Swiss Airliner spotted him and gave him the frequency beacons that helped him flying to Dar es Salaam, where both Ochuka and Oteyo wanted to seek political asylum.

But there was another problem as he would say later:

“I had no clearance to enter Tanzania and (by the time I approached Dar es Salaam) I was left with fuel that would not last me more than five minutes,” he said.

As the fuel ran low, Maj Leshan’s fate now lay with Tanzanian authorities who were refusing to let him land. Then he declared an emergency.

“I informed them that I had a man with a gun behind and that I had run out of fuel before I declared emergency landing at the airport,” Leshan told the court.

Once in Dar es Salaam, Ochuka had sought political asylum and claimed to be the chairman of People’s Redemption Council.

But in Nairobi, on August 12, the Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions Sharad Rao sought a warrant of arrest and extradition on the two Kenya Air Force men who had escaped to Tanzania.

He got the order issued by Chief Magistrate Abdul Rauf.

As Kenya sought to have the two extradited to face kidnapping charges– rather than staging a military coup— Ochuka claimed in court that Maj Leshan and Maj Marende were members of the “presidential escort” and thus had not been kidnapped.

Ochuka told magistrate Goodwill Korosso that Leshan readily accepted to fly the two coup plotters to Tanzania and that his flight was political.

On September 21, the Tanzanian court agreed with Ochuka and dismissed Kenya’s bid to extradite the two fugitives, saying it found no proof that the two KAF majors had been kidnapped.

The magistrate said the evidence clearly showed that the two majors had agreed to the plan to flee to Tanzania and might have conceded to the idea after realising that their lives were in danger in view of the onslaught by government forces.

“It is highly probable that the two majors agreed to come to Tanzania in fear that the safety of their lives was in danger and the only way to save themselves from advancing infantry forces to the Eastleigh airbase was to escape to Tanzania. After all, the two majors had no ranks on them to distinguish them from other servicemen,” said Mr Korosso.

The magistrate accepted “the good-natured and good-willed” Ochuka’s defence that he had confidentially discussed with Maj Leshan the flight plan to Tanzania without the knowledge of the other servicemen.

Having failed in having Ochuka extradited, Leshan was flown back to Kenya in late August and was absorbed back into the new 82 Air Force.

He was accompanied by an assistant commissioner of police A.M Khan.

Also, Tanzania said it would not help Kenya pursue appeal and declared that the ruling was final.

But on November 11, 1983, in a surprise turn of events, both Ochuka and Oteyo were brought back to Kenya after the government of Julius Nyerere entered into a political deal with President Moi.

They then faced a court martial led by Judge Peter Gray and were charged with organising the 1982 coup and Leshan was one of the key witnesses.

For that effort, he rose to become a decorated soldier and one of the few Kenya Air Force survivors.

Many others were not as lucky – and had their career end up in turmoil. On Friday, Leshan died with his other side of the story.