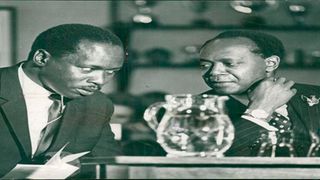

Daniel arap Moi (left) and Charles Mugane Njonjo.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

How Daniel Moi brought down Charles Njonjo

It was April 1983: Charles Njonjo was busy shopping in London. As usual, and from his tailors in that city’s Savile Row, he would bring President Moi some designer suits – the best that money could buy.

Back in Nairobi, while Njonjo was away, his detractors were laying the strategies for taming his rise in the Nyayo government. Moi and Njonjo not only shared a tailor but had the same personal doctor, Chicago-born heart specialist David Silverstein.

When the time to part came, those alliances became footnotes.

It was eight months after the August 1982 coup attempt, which Moi used as an excuse to purge the Kenyatta-era security and intelligence system.

Moi knew about the planned Hezekiah Ochuka-led coup and had been alerted about it by the intelligence – only that they did not know the date it would happen. With all the security men thought to be allied to Njonjo gone, he was now politically exposed.

That May, Moi told a rally in Gusii Stadium that Western governments were grooming a person to take over Kenya’s leadership. Later that day, as the Presidential Press Unit was compiling the bulletin, Moi walked in.

Witch-hunt

“Hiyo ya traitor ndiyo story,” he told the then PPU editor, Cornelius Nyamboki.

From then on State House became a witch-hunt site as different groups sought to find evidence to crucify Njonjo and a well-orchestrated campaign on the traitor was launched.

Njonjo had returned with the suits from Tobias and went straight to State House to pledge loyalty. He tried several times and as he narrated later to Moi biographer Andrew Morton, “Moi would rush out straight past me. When I tried to see him, he was not available. I am an old man in this game, and I knew that something was afoot.”

To keep the traitor saga going, the Muungano National Choir, led by Boniface Mghanga, had been asked to compose a song, “Msaliti”, which was always played by the Voice of Kenya before the news.

Njonjo’s denial and pledge of loyalty did not silence his critics – although nobody had named him by that time.

Both Njonjo and the diminutive G.G. Kariuki had formed the habit of riding in the presidential limousine to the extent that some Moi handlers thought they disrespected the President. “At State House Njonjo’s lunchtime cocktail and his habit of paddling around (Moi’s) office in socks caused comment,” wrote Moi’s biographer Andrew Morton.

“People were asking, ‘who is the president? Is it Moi, Njonjo or Kariuki,” John Keen, then an assistant minister, told Morton.

By this time, according to Morton, there was talk that Mwai Kibaki, then Vice-President, might leave for a World Bank position. Njonjo, who had quit as Attorney-General and bought the Kikuyu parliamentary seat from Amos Nganga for Sh160,000, had negotiated with Moi that upon election he would be appointed minister for Home and Constitutional Affairs.

Very nervous

By 1980, two groups had emerged in Kanu - one led by Mwai Kibaki and another by Njonjo. “Obviously Kibaki was very nervous, because he thought that I was going to take over his job. I did not want the post of Vice-President,” Njonjo told Morton.

He claimed that the bad blood between him and Kibaki started the day he suggested to Moi that Kibaki become Vice-President. That evening he went to break the news to Kibaki at his Muthaiga home. “From that day on Kibaki became my enemy,” claimed Njonjo.

In early 1982, Moi hived the Home Affairs portfolio from Njonjo and assigned it to Kibaki, who had to leave the Finance ministry. Quietly, Moi and his henchman questioned Njonjo’s entry into politics – but whether Njonjo was up to some political mischief was still not clear.

After the coup attempt, State House became a no-go zone for politicians and Moi brought in a new set of homeboys and get-rich-quick denizens of the political kingdom. Overnight, he changed from an easygoing President into a perfect dictator.

But Njonjo was still standing strong, surrounded by his circle of African elites and European and Asian friends. Without a political base, and with no grassroots support, Njonjo was floating like a balloon.

He was also a stumbling block to Moi’s recognition in the diplomatic community, which felt comfortable with Njonjo due to his right-wing pro-Western stand. At home, his contempt for other politicos became his undoing.

Thus, when Moi in May 1983 alleged that there was another plot against him – and even before Njonjo was named in Parliament by Tourism minister Elijah Mwangale – it was all clear that Njonjo was the man.

Two days after the Kisii rally, Kibaki and Kerio Central MP Francis Mutwol had thrown out some hints. Mutwol, then secretary to Kanu's parliamentary group, claimed that "the traitor is a minister" while Kibaki said the traitor would be "shown no mercy".

Both Kibaki and Mutwol had missed a May 10 National Youth Service graduation parade presided over by Moi in Gilgil and were in Nairobi setting the stage for the upcoming purge.

Njonjo felt betrayed and said as much later. “Here is a man whom I have worked with and helped and done everything for. He hasn’t called me to ask me about these accusations…he had believed everything he had been told by Simeon Nyachae, that I had something to do with the coup and that I was undermining the government.”

It was at Nyachae’s home that the plot to bring down Njonjo was hatched. Then Njonjo made a political blunder.

On June 12, at the height of the traitor issue, he attended a service at the Rungiri Presbyterian Church in Kikuyu. In his sermon, city businessman and church elder Samuel Githegi asked the congregation to pray for Njonjo. He then quoted a Kikuyu proverb, which translates that when a flock is led by a limping sheep it never reaches the grassland.

That Tuesday, Parliament adjourned its sitting to discuss the sermon, with Lurambi MP Wasike Ndombi alleging the “limping sheep” was a reference to President Moi. He was supported by Martin Shikuku, who led the parliamentary push against Njonjo.

The die was cast. On June 26, Moi announced the formation of a commission of inquiry to “investigate” Njonjo’s alleged treasonous behaviour and the conversion of a church meeting into an “irregular political meeting”. The chairman was Justice Cecil Miller, with Justice C.B. Madan and Justice Effie Owuor as commissioners. The joint secretaries were Jared Benson Kangwana and Benjamin Kubo.

Other allegations against Njonjo were that he had acted against national interest and policy by working with South Africans and conspiring in November 1981 to overthrow the “brotherly “government of President Albert Rene (of Seychelles) when Moi was the chairman of the Organisation of African Unity.

The Miller commission was also to investigate allegations that Njonjo “arrogated to himself duties and powers of the president” and “attempted to make corrupt payments, granted favours…to seek political support”.

For the next 109 days, Njonjo was taken through a torturous political journey as his lawyers William Deverell and Paul Muite fought to save him.

The first allegation was that a wealthy Indonesian family, the Haryantos, were keeping a huge cache of weapons near State House. Njonjo was a friend of the family and was the best man at the wedding of one of Yani Haryanto’s sons.

When the commission was taken to the home on Lenana Road, they were shown 20 rifles, six revolvers, two shotguns and five boxes of ammunition containing 3,684 rounds. There were also 5,575 cartridges and two tins of airgun pellets. In total, the extended Haryanto family had more than 100 guns.

While the Haryantos were hunters and had a camp in the Maasai Mara (at a time when hunting was banned) the inquiry questioned the “powerful” communication equipment found at their home. Locally, with Captain Boscovic and Njonjo, they owned an aviation business, Boscovic Air Charters.

So powerful was Njonjo that when his friends arrived at the airport, they would be accommodated at the VIP lounge and their luggage was never checked. The onus fell on Njonjo’s official driver, Chief Inspector Kabucho Wakori, who would tell the inquiry that he would collect luggage containing guns while the Firearms Bureau chief licensing officer, Douglas Alan Walker, was busy with the guests at the lounge.

Walker would later say that he followed the Haryantos to their home and inspected the guns there. At times, he received free guns from the Haryantos and kept poor records on the number of weapons the family had.

Another cache of weapons had been brought in by American Kent Crane. Njonjo’s secretary, Penny Hill, had asked Wakori to pick up the guests. Njonjo’s Mercedes Benz (KVD 710), which he had sold to the Haryantos but was still in his name, was used for that purpose.

When an inquisitive security officer asked what was in the luggage, the Americans claimed it was food and fishing rods belonging to Njonjo. And before the tussling was over, the firearms registrar arrived with a permit book. He inspected the guns and let the Americans leave.

The imported guns included a prohibited 7.62mm rifle. While Walker - after he reported to Police Commissioner Ben Gethi the importation of that gun – was asked to send it back, the commission was not shown any evidence of imported guns.

Njonjo was also accused of allowing South African nationals and members of the apartheid regime to enter Kenya. Among the high-ranking officials that he asked Principal Immigration Officer Joseph Mutua to let in were Lt-Col F.A. Van Zijl of the SA armed forces and a Mr J. Lockley, who previously worked as a police officer in Kenya before joining the South African police force.

On the allegation that Njonjo had used his position to undermine President Moi, the commission heard evidence from Karisa Maitha, then a clinical officer in Mombasa, who alleged that he was approached by Mombasa North MP Said Hemed and asked to resign his job and contest the Bamburi Ward seat.

This was used as evidence to show that Njonjo was trying to win support from various tribes. After Maitha’s election, the commission was told, Njonjo and Duncan Ndegwa tried to coax him to ask some squatters to leave 444 acres they partly owned. When he refused, he was expelled from Kanu – though he was reinstated after a week.

Another MP, Lawrence Sifuna, claimed that Njonjo was using money to influence MPs. He told the commission that Njonjo had compiled false mileage claims on all MPs, and those who crossed his path had their files sent to the Criminal Investigations Department, then under his ministry.

MPs with a complaint against Njonjo lined up to crucify him: Francis Mutwol, Mashengu wa Mwachofi and many others. Fred Gumo, then Kitale East MP, even claimed that Njonjo had sent him to tell President Moi to combine the AG’s office with the Ministry of Constitutional Affairs because James Karugu was messing up.

Unconstitutional objective

“To be evil is an art itself. On the evidence, we are satisfied that Njonjo decided to pursue his unconstitutional objective…associating with incipient criminals and equally disloyal persons” to undermine President Moi.

On the allegation that Njonjo was involved in the August 1982 coup attempt, the man of the moment on the witness stand was Raila Odinga, then in detention. Odinga claimed that he had a conversation with Deputy Speaker Kiprono arap Keino, who told him that Njonjo would make it as the next President. But Odinga told Keino that Njonjo could not win a free and fair election.

In 1981, Odinga said, he had started investigating Njonjo’s plans to destabilise Uganda by financing opposition groups. When Odinga was later arrested after the 1982 coup he was asked to write a statement, before Police Commissioner Gethi, on what he knew.

In the statement, Odinga alleged that he had received information that Njonjo had plotted to overthrow the government on August 5 with the aid of South African and Israeli mercenaries and the General Service Unit. He also alleged that he had intelligence that the guns were kept in the Aberdares.

Gethi, Odinga claimed, tore up the confession every time a reference to Njonjo was made. He refused to admit that he was involved in plotting the August 1, 1982 coup and was detained.

It was this allegation – the Haryanto guns and the attempt by Njonjo’s first cousin, Mungai Muthemba, to purchase military arsenals – that would fix Njonjo.

Another man who would fix Njonjo was the late Dr Robert Ouko, who claimed that he was instrumental in the demise of the East African Community. Njonjo never hid his position on EAC and when a team comprising Njonjo, Kibaki and Dr Ouko met in Arusha to help salvage the body in 1976, Njonjo approached Dr Ouko and asked him: “Why are you fighting so hard to maintain this thing?”

“Which thing?” Dr Ouko asked.

“This East African Community of Yours” retorted Njonjo. “Forget it…let it break!”

Finally, Njonjo was found guilty of involvement in the Seychelles coup and for enlisting mercenaries. He travelled with four valid passports and had four diplomatic passports bearing the same serial number. Some had not been recorded in the register.

On corruption, he was found to have influenced the awarding of a contract to print new passports to Bradbury even though the company had asked for more money than competing bidders.

Asked to take the stand, Njonjo disappointed the commissioners, opting to make a short speech.

He refused to be led in evidence by his lawyer and said: “It is over a year now since the inquiry was set up and we have 102 days of hearings. This has been an unpleasant and sad and a humbling experience for me.

“But I do believe that the very fact that such proceedings have taken place is a tribute to the maturity and stability that exists in our country and the Christian wisdom of His Excellency the President. And in trusting in the wisdom and fairness of His Excellency, I have asked my two counsel to keep any further proceedings here as short as possible.”

With that, Njonjo refused to respond to any of the allegations. It was his style – and he knew the drill. After all, it would not make a difference.

[email protected]

@johnkamau1