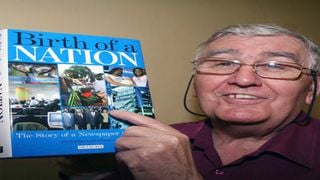

Gerry Loughran with his book on March 13, 2010.

| File | Nation Media GroupGerry Loughran, the stickler for factual accuracy and journalistic flair

What you need to know:

- As a consultant editor at the Nation Group between 1993 and 1998, he wrote the earliest concept papers on what is now The EastAfrican.

- Gerry guided young reporters; he was ever considerate, thoughtfully generous and duty-conscious to a fault.

His quiet professionalism always carried the day. Whether it was the knock-out humour at the bottom of a weekly newspaper column or a hastily spun recollection of Kenya’s political or media history, the stories were written with journalistic flair and an old-fashioned respect for factual accuracy.

Last week’s death of Gerry Loughran, the Sunday Nation’s Letter From London columnist, brought to a close a distinguished media career, two strands of which played out in Kenya.

One was closely intertwined with the story of Nation Media Group’s growth from a single newspaper in the 1960s to a regional news publisher two decades later.

The other carefully retraced, in political drama and colourful characters, the post-independence chapter of Kenya’s political evolution through the pages of Birth of a Nation, the Story of a newspaper in Kenya.

Although Loughran’s association with Nation Media dated back to the group’s formative years at Independence – during which he helped to set up the Sunday Nation and served as its Assistant Editor – it was for his role as one of the prime movers in East Africa’s first regional newspaper that he will be remembered by the latter generation of Nation journalists

As a consultant editor at the Nation Group between 1993 and 1998, he wrote the earliest concept papers on what is now The EastAfrican. By his own admission, steering and bringing forth The EastAfrican – an issue-driven weekly produced in Nairobi and distributed with the region – was the high-water mark of an adventure-filled career spanning 49 years, which had seen him cover conflicts in different parts of the world, especially the Middle East, as a foreign correspondent

“I consider planning for, arguing about, working on and promoting this newspaper to be a career highlight – the most challenging, exciting and ultimately rewarding of many tasks over the years,” he wrote during The EastAfrican’s 20th anniversary. “That the newspaper not only exists but flourishes going into its third decade, is something we, pioneers, would hardly have dared to predict.”

Loughran was working as a part-time correspondent from his cottage in Scotland in 1993, when the then Nation group managing editor, Wangethi Mwangi, telephoned and invited him to Nairobi to join the thinking group for a proposed regional newspaper

The publishers of the Daily Nation and Sunday Nation, had long-held ambitions to widen their newspaper’s reach. After all, the title of the founding company was East African Newspapers Ltd and as far back as 1970, the founder and proprietor, the Aga Khan, had expressed the wish for “at least one prestige publication of high quality circulating throughout East Africa”.

Loughran accepted Wangethi’s invitation and, returning to Africa, launched a market survey, talking to a wide range of news and business people, testing the temperature in the three capitals. His conclusions were entirely positive and a decision was made to develop the newspaper to ride on the revival of regional integration nearly two decades after the East African Community’s collapse.

That was the stage at which I entered the project as the proposed newspaper’s editor-to-be, together with the late Jerry Okungu, who would be marketing manager. I’d just returned to Kenya from a year’s postgraduate studies at the University of Wales, Cardiff. Our triumvirate embarked on thousands of kilometres of travel, arranging focus groups, cocktail parties, face-to-face meetings and discussions with readers, advertisers and distributors in Nairobi, Mombasa, Kisumu, Kampala, Arusha, Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar.

Having established the need for a regional paper, debate focused on how often it should come out, what size it would be and what it would look like. Even though most of the discussions were recorded, Loughran would take copious notes, which later helped to resolve key issues. His reports made it clear that the project would require a huge commitment of resources. Secondly, a magazine did not seem the right vehicle for this type of project, nor did an insert or special section in the daily or Sunday Nation, and so the decision was taken to go for a separate, upmarket, weekly tabloid.

A final contentious matter was the title. Loughran’s suggestion of The EastAfrican, with “East” and “African” as a single word, suggesting a single entity, baffled many. Why not The East African Nation? Our response was that to use the word Nation would signal “Kenya” to the other two countries. A regional identity in the title was important and we instanced The Scotsman, The Sowetan and The Austral- ian as successful precedents.

Staffers were hired and East African presence established in Dar es Salaam, Arusha and Kampala; two brilliant columnists were recruited — for Kenya, John Githongo, destined for celebrity as the country’s anti-corruption warrior, and in Kampala, Charles Onyango-Obbo, whose chatty but searing style was a revelation.

If as managing editor I drove the team of reporters and sub-editors with the zeal of an orchestra manager keen to top the charts, Loughran was the band conductor par excellence. Fridays and Saturdays, our production days, saw the former UPI foreign editor in full plumage. He would be hunched over a computer keyboard for hours, rewriting stories, cleaning up pages and changing headlines before I reviewed them and vice-versa.

Loughran and I knew exactly what we wanted with The EastAfrican and by the time of the launch issue, all hands were routinely meeting unaccustomed standards of precision, accuracy and aesthetics. Issue 0001, which rolled off the press on November 7, 1994, was calm, reflective, and authoritative – a revelation to readers used to busy pages and shouty headlines. Not known for extravagant compliments, Loughran was overjoyed with the paper’s quality and, in a gruff Geordie accent, openly commended the team at the next Monday’s editorial conference.

Some 18 months after The EastAfrican’s launch, the International Press Institute, assessing the state of the world media, said, “One of the best, if not the best of regional newspapers in sub-Saharan Africa, is The EastAfrican, providing readers with sober, incisive news of issues and events. Such a newspaper is far ahead of the political leadership of the region. The EastAfrican is proof that commerce, travel, the environment and culture tie the region together logically.”

Slowed down by corporate bureaucracy and his own investigative zeal, Loughran took nearly 15 years to complete Birth of a Nation, the Story of a Newspaper in Kenya. He pursued former employees across the world, tape-recording their recollections and tirelessly writing and rewriting the book’s chapters as new information came to light. Only a few of them, such as the Nation’s controversial editor-in-chief of the 1970s, George Githii, who had found a new life as a preacher in Canada, managed to escape his dragnet.

Ever the voracious news hound, Gerry gladly abandoned his desk at Nation Centre at Wangethi’s request on 1994 and, together with Nation correspondent Ngugi wa Mbugua, travelled to Rwanda to report first-hand the epic killings by Hutu extremists as the Rwanda Patriotic Front marched into Kigali. A year later, they returned to the killing fields and compiled a special report on the nation’s struggle to heal and its efforts at political and economic reconstruction, setting the Nation and The EastAfrican apart as newspapers of record.

Loughran held on to old-fashioned decency as firmly as he defended editorial principles and the media’s right to publish. Our heated debates on whether or not to run a provocative story or how to make an investigative scoop safe from political reprisal always ended with a softly spoken but firm reminder that self-censorship was the quickest route to media’s self-destruction.

“You are damned if you publish and damned if you don’t,” he would stress in his soft but firm manner. “Stave off official anger now, but that is only short term. In the end your readers and advertisers will desert you.”

That was the position he took over the Eldoret arms factory story published by The EastAfrican at the height of corruption and repression under the Daniel arap Moi government. Questions had been raised in the Belgian parliament about the proposed construction of a bullet factory in Eldoret at Ksh15 billion. Although Nairobi insisted the plant was the Kenya military’s, critics claimed the construction contract had been signed between Belgium’s state-owned arms supplier and three Kenyan politicians.

With nothing more than parliamentary allegations to go by, my instinct was to push for independent documentary proof, which we were unlikely ever to get hold of. Loughran drew on his international contacts and rudimentary French to cross-check the claims by Belgian MPs. His findings, together with additional juicy details from anti-corruption crusader John Githongo, gave us the confidence to publish in the end.

Modesty should have been Loughran’s middle name. Mixing with the highest authorities at Nation Media never prevented him from cultivating a network of young reporters and rural correspondents as personal friends, whom he tutored and sometimes took on road safaris across Kenya. He took time to guide them on editorial projects and rewrite their stories. It was typical Gerry – ever considerate, thoughtfully generous and duty-conscious to a fault.