University education is available to all but let us make it accessible

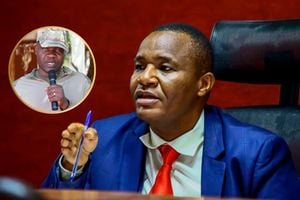

Maseno University Vice-Chancellor Julius Nyabundi and first-year students during orientation at the institution on September 19, 2023. There is confusion in the implementation of the new university funding model.

Unesco published a report on the status of global higher education last year. One of its highlights was the improvements made by governments in expanding access to university.

At the international level, the Unesco Higher Education Global Data Report showed that enrolment had risen to 220 million in 2020, nearly doubling the figures recorded two decades earlier.

To put it in context, enrollment in higher education had reached 40 per cent internationally, meaning that one in four eligible people was in college.

However, this was a global figure that masked wide disparities and harsh realities. On nine per cent of those eligible are enrolled in higher education in Africa, and then, just in a few countries.

From the statistics, the masked truth is that higher education remains a preserve of a few in Africa and in many other parts of the world.

Which is the reason for the persistent calls for reforms and revitalisation of education systems to expand access across all levels.

Recently, Education CS Ezekiel Machogu made a major pronouncement on grading of Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) examinations.

The broad objective is to improve transition from high school to university and tertiary education.

The minister stated that the criteria for grading students would change this year from using five compulsory subjects to only two – mathematics, English or Kiswahili or Kenya Sign Language – at the KCSE examination.

This is a departure from the past, where grading incorporated five compulsory subjects – mathematics, English, Kiswahili, two sciences and one humanity.

Even so, this is not new. It is a return to the old practice of early specialisation under the system before 8-4-4.

Then, Form Four students took seven to eight subjects and only two – Maths and English/Kiswahili were compulsory. Thereafter, and based on performance, students transitioned to Advanced Level (Form Five and Six) to specialise in three subjects and then proceeded to university.

The reasons behind the grading change are many. Many KCSE examination students fail to qualify for university education because the curriculum requires them to pass in the five compulsory subjects and others.

Thus, the learners are pushed to work hard and excel in a whole range of subjects, even those that are not relevant to their preferred career choices.

Yet, given an option, they would select a set of subjects they are confident about, work hard on them, pass and progress to tertiary institutions.

Opinion is divided, though, on the rational for reducing compulsory subjects at Form Four.

Whereas the new thinking may be viewed as opening gates by dismantling barricades that unnecessarily block many learners from progressing to university, the contrary view is that having a range of compulsory subjects prepares an all-round learner and opens many opportunities in higher education.

However, the substantive question is; how do we expand access to university education?

Generally, fewer than 20 per cent of high school leavers transit to university. Last year, for instance, only 173,345 out of 881,416 KCSE examination candidates – 19.62 per cent – qualified for university admission.

Considering that up to 40 per cent of those who register in Standard One drop out before reaching Form Four, it means that those joining university are just about 10-12 per cent in any cohort.

This is a mark of high level of wastage in a country’s education system.

One way of addressing access is dealing with this is through technical and policy interventions.

This is where the grading policy comes in. But this is the supply side. The other is the demand.

And this raises fundamental questions; do we have attractive universities and programmes that students would genuinely long to join? Do the institutions adequately prepare learners for the job market? Are there sufficient and attractive jobs for university qualifiers?

Records from the Kenya Universities and Colleges Central Placement Services (KUCCPS) provide significant indicators about the demand for higher education.

For example, out of the 173,345 candidates who obtained grade C+ and therefore qualified to join universities, some 140,107 applied, meaning that more than 30,000 or 20 per cent, did not.

Second, out of the 545 degree programmes on offer in the universities, more than 100 did not attract students.

The inference is that there are many students who opt not pursue university education. Moreover, many of them consider various courses irrelevant.

Beyond these, financing will increasingly determine admission to university.

In line with the recommendations of the presidential working party report made public in May, the government has lifted cap on university fees and allowed every institution to charge courses at market rate. Consequently, university fees have shot through the roof.

Concomitantly, the government has introduced a funding model that operates on a tier-basis and is designed to benefit the most needy.

It is too early to assess the efficacy of the new system, but early reports indicate that many households are struggling to raise the fees.

Moreover, there is deep confusion in implementing the new funding model, given that even the actual cash is not available.

Thus, the question of expanding access to university remains and the onus on policy makers and managers of higher education institutions is to rethink better strategies to open the gates for more deserving students.

Efforts to tackle the supply side must be complemented by those that address the demand side, which includes institutional reforms.

The fact that higher education is available does not necessarily mean it is accessible.

David Aduda, Consulting Editor, is an Education Specialist. [email protected]