The late Daniel Arap Moi.

Days to the August 1 1982 coup, Captain Hussein Ahmed Farah (now a retired colonel) was in a military parade during an event in Nyeri where President Moi had the last public engagement before the attempt to overthrow his government. He sheds new light on events leading to the mutiny.

It was a chilly Wednesday, July 29, 1982. Kenya Air Force officers had mounted a colourful military parade rehearsal. Then Chief of General Staff Jackson Mulinge and Air Force Commander Peter Kariuki were impressed with the guard of honour. All was now set for President Daniel Arap Moi, the Commander-in-Chief, to inspect the parade on Friday, July 31, during the official opening of the Agricultural Society of Kenya (ASK) show in Nyeri.

Satisfied with the show their charges had put up, the parade commander, Major John Serem, and his deputy Captain Hussein Ahmed Farah, escorted the generals as they left. (Serem, who later rose to Major General, died in 2005).

Farah, who had joined the Air Force in 1971, recalls a conversation he overheard between Mulinge and Kariuki. Mulinge asked the air force commander: “That Lt Mwambura, has he been arrested yet?”

“I will get him arrested on Monday,” Farah quotes Kariuki replying to his boss.

Farah knew Lt Lislie Mwambura was in charge of logistics and stores in Nanyuki airbase. He thought the disciplinary action must have had something to do with lost items. The generals left and everyone was not looking forward to Friday’s action.

Farah, a squadron commander and UK-trained flying instructor, was particularly keen on what was to be his last parade if his boss had kept his word.

Retired Col Hussein Farah during the interview at his office at Bluebird Aviation at Wilson Airport on July 30, 2024.

The soldier who loved his action in the cockpit of an attack aircraft was getting frustrated at frequently being asked to join a parade. As a general duties officer, a soldier, even a pilot, can be deployed to carry out whatever task their senior direct.

In 1981, Kenya hosted an Organisation of African Unity (OAU) meeting and Farah had also been detailed as an aide-de-camp of one of the visiting presidents.

Somehow, Farah had become a favourite of his seniors who often assigned him to military parades.

Final parade

“I felt I was losing a lot of my flying time in parades,” Farah- one of four pilots commissioned at State House by President Jomo Kenyatta- recalls complaining to his boss.

But his seniors nominated him to be the deputy commander for one final parade at the Nyeri ASK show.

“He told me; ‘I promise you this will be the last parade,” Farah remembers the assurance which would turn out to be true but not an end to parades that he would have wished for.

“I can never forget that day,” Farah, now chairman of Wilson airport-based Blue Bird aviation, says of the ceremony on Friday, July 31, 1982, during an interview with Nation.Africa on Tuesday, July 30, 2024.

Some odd occurrences caught his attention after the successful parade that afternoon. President Moi addressed the public and then left the dais. But shortly after, an odd announcement was made through the public address system. The crowd was asked to remain attentive as the president was coming back to make another address.

Police officers guard looted property recovered from a lodging in Kirinyaga Road, Nairobi, following the failed coup attempt on August 1, 1982.

“President Moi was to get into his vehicle but the convoy never left. Instead, someone comes to the microphone and announces the president would speak again. We had never seen anything like that before. It was very strange,” Farah recollects. The Head of State then made a lengthy speech largely about national unity and extolling the government’s achievements.

It would later emerge that the presidential guards had brought back the president as a security precaution as an incident was being sorted out.

“Apparently, there was a security scare. We were told later that some unidentified people who were armed had infiltrated the president’s convoy and they were caught. But we never came to know exactly what had happened,” Farah reveals.

This incident and the earlier conversation between the generals about the arrest of an officer- the only officer recruited by the soldiers for the putsch- are the clearest indications that the coup was known to the intelligence.

Court martial proceedings

During court martial proceedings against Kariuki, the army commander whose tenure abruptly ended in a jail term on accusations of failing to suppress a mutiny, it emerged on July 14, 1982, Laikipia Airbase commander, Col Felix Njuguna, had informed Kariuki about Mwambura.

Njuguna had reported that Mwambura had informed him that Sgt Joseph Ogidi had approached him and disclosed that he and others wanted to overthrow Moi’s government.

According to the proceedings, Kariuki telephoned Lt Gen John Sawe, the army commander, who was also Mulinge’s deputy. Mulinge directed that the information be shared with the military intelligence and special branch.

On Friday at the Nyeri ASK show, Director of Special Branch James Kanyotu asked for Moi’s permission to arrest the coup plotters. Moi turned to Mulinge and the CGS, according to the proceedings, asked that it be done on Monday.

A Kenya Air Force rebel on top of a car addresses a crowd at Kariobangi Petrol Station on August 1, 1982.

Apparently, the attempted coup offered Moi, who had overcome resistance to assume the presidency after the death of Jomo Kenyatta in 1978, a reason to tighten his grip on power by purging the establishment including security forces. In an interview with this writer in 2014, Mr David Musila, who served as Central provincial commissioner at the time of the coup, suggested Moi had prior intelligence about the coup but somehow allowed it to continue. Two days before the coup on Friday, July 30, 1982, Moi had officially opened the Nyeri Agricultural Society Show. Earlier that day, Musila had accompanied the president from State House, Nairobi on the road to Nyeri. “He had told me he would be coming to Sagana State Lodge but later told me he wouldn’t stay there but that I should not change the arrangement,” Musila recalled. “We had lunch at my house then at around 4pm he directed the beating of the retreat- lowering of the flag- at Nyeri Showground,” he disclosed. “We drove to Nakuru with my car ahead of his. Over dinner he told us that ‘you people must look after this country and not allow it to go to the dogs,” he recollected. Musila would get wind of the coup attempt the following day from intelligence reports. “I recalled the cutting off of the function, him putting off his stay at Sagana Lodge and wanting to drive to Nakuru. He was cautious about what was happening but maintained a fearless posture which I found amazing,” Musila observed.

Farah also corroborated this account of Moi changing his schedule to spend the night at Sagana State Lodge and instead driving to Nakuru.

Back at Ruring’u Stadium, the venue of the ASK show, after the security scare, little did Farah know that even more drama- and terror- awaited him and his team of about 145 Air Force officers. The contingent that was supposed to leave Nyeri that evening sought permission from their seniors to spend the night there as it was heading to the weekend. The idea was to allow the soldiers a day off on Saturday. That permission was granted and the soldiers spent another night at Kenya Police Training College in Kiganjo where they had camped.

Civilians caught up in the attempted coup of August 1, 1982 walk on the streets while displaying their ID cards.

But they had to surrender their guns which were picked by a helicopter that was en route to Nairobi on Saturday morning. This would be a decision they would live to regret given the events that unfolded on Saturday night.

Chilling news

At 6am on Sunday, a sergeant major in charge of the servicemen frantically woke up Farah with chilling news. He spoke in Swahili. “Hawa vijana wanasema ati radio inasema serikali imepinduliwa na wanajeshi (The soldiers are saying there is a radio broadcast that there is a coup),” he recalls the startling report. Farah asked his junior to fetch the radio. Congolese Lingala music was playing at the time. Farah told his colleague if there had been a coup, martial music would be playing. Then the music was interrupted and the familiar voice of veteran announcer Mambo Mbotela repeated the broadcast about the coup. The rider in the announcement that “police are directed to assume civilian role” had a sense of irony given the soldiers were holed up in a police college.

That’s when Farah went to inform his senior, Serem, about the dramatic development. Later, senior police officers joined them. Two low-flying fighter jets flew past and when Serem remarked they were armed, “some of the police officers dived for cover” an act Farah found amusing. Serem and Farah resorted to their Air Force Land Rover equipped with communication installations to listen in on what was going. They overheard the chaotic orders by the coup plotters. “They didn’t appear to have a language of command,” Farah recounts. He cited an instance where one pilot in northern Kenya inquired through the radio communication what was happening only for the air force soldier on the other end to reply rudely. Farah, who grew up in Nanyuki during the Mau Mau uprising and is fluent in Kikuyu, recognised his colleague who had called in from northern Kenya telling him in the native language: “Muriuki, leave this matter alone.” The pilot recognized him too and cut off communication. To date, the two friends joke about this Kikuyu phrase.

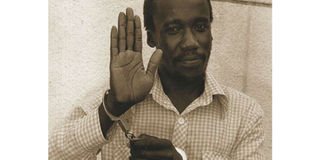

The leader of the August 1, 1982 failed coup, Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka.

By 10am, Army Commander Lt Gen John Sawe had scrambled a counteroffensive led by his deputy, Major General Mahmoud Mohammed, who led loyal forces to recapture VoK. The announcement that the coup had been crushed was a relief for many, but the beginning months of nightmare for the 145 Air Force soldiers grounded in Kiganjo police college.

For starters, the policemen were becoming hostile to the soldiers following the reports branding Air Force personnel coup plotters. They were running out of food rations. The announcement by President Moi on radio in a 7pm broadcast blaming the air force for attempting to overthrow his government only worsened the situation for the besieged soldiers. They were informed army trucks will only come for them the following morning. “It was the longest night ever,” Farah says. The hostility of the commander of the army unit that came for them in the morning left no doubts that they weren’t being rescued. “He wouldn’t even let me lower the KAF flag but I stood my ground. This was probably the last KAF flag flying in the entire country,” he recalls with admiration, “and I am glad we did the ceremony to hoist it down.”

Humiliating screening

At Laikipia Air base, which had been overrun and seized by the army, Air Force soldiers were squatting on the tarmac as the humiliating screening got underway. Brigadier James Lenges (he later rose to Major Gen), who was now in charge of the base, however, according to Farah, ordered the air force personnel who had been trucked from Kiganjo police college to be isolated at a newly built sergeant’s Mess. They were detained there for three days.

Maj Gen Mahmoud would later visit the Laikipia airbase and order the soldiers to be trucked to Nairobi. “He told us we had to explain why we gave up our arms and whether it was part of a scheme for the weapons to be used by rebels,” Farah recalls. In the end, the group was vindicated. Mahmoud would later be named commander of the newly formed 82 Air Force after the disbandment of KAF.

Much later, Farah would find himself among a crew of four that flew President Moi to Mombasa. On arrival, he recalls cabinet minister Stanley Oloitiptip asking Moi: “You still trust these guys?” Moi however told him off. However, it would later dawn on them that each had been privately asked to keep watch over the rest. “That is how we found ourselves at our next stop in Tanzania staying awake until one of us, tired of the suspicions, revealed he had been asked to watch over us. Turns out that was everyone’s brief!”

The reason they were a crew of four was because the other mission in Tanzania was to retrieve the military buffalo plane that coup plotters had fled into Dar Es Salaam International Airport. Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka and Sergeant Pancras Okumu had commandeered the plane with the pilots Maj Nick Leshan and Maj William Marende. “In a twist of fate, the Tanzanian authorities took us to the same hotel where Leshan and Marende were being held. The two asked us what their fate was but frankly, we had no idea,” Farah recounts. “The two had flown the plane barefeet after abduction by Ochuka,” Farah adds with a chuckle.