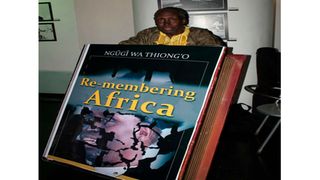

Ngugi wa Thiong'o during the launch of his book ‘Re-membering Africa’ in Nairobi on August 5, 2009.

| File | Nation Media GroupWeekend

Premium

Why we must all work to save our mother languages

What you need to know:

- Pushed to the fringes of everyday usage, our mother languages are dying every day an elder dies.

- Even the controversial CBC now being rolled out is unlikely to inject new life into the thinning of our mother languages.

The celebration on February 21 of the International Mother Language Day demands that we revisit some of the outstanding debates in literature and learning about our shared plight, first as former colonial subjects whose indigenous languages were systemically derided by the colonial machine, and second as a basis to imagine how best we can assert our belonging to a future cosmopolitan world that will only respect us if we have our languages.

For recollection’s sake, the debate on the role of language in defining ourselves was initiated by Obi Wali’s 1963 article entitled “The Dead End of African Literature”, which was a response to the proceedings of the Conference of African Writers of English Expression held a year earlier at the then Makerere College in Uganda.

Noting the exclusion of Amos Tutuola’s works from consideration at the conference; the use of European and American templates in interpreting African literature; and the uncritical embrace of English and French as the languages of literary expression, Wali reached a grim conclusion – seen in his title’s metaphor of a cul-de-sac – about the future of African literature.

For Wali, “until these writers and their Western midwives accept the fact that any true African literature must be written in African languages, they are merely pursuing a dead end, which can only lead to sterility, uncreativity, and frustration.”

Wali’s lament would somehow be ignored until the mid-1980s, when Ngugi published the globally influential Decolonizing the Mind, a collection of powerfully argued essays that pitch for the importance of mother languages in shaking off traumas of colonialism.

At the core of Ngugi’s intervention is the fundamental point that a people’s ultimate freedom from neo-colonialist machinations can only be through mother languages, a point that has been well nuanced since then.

Indeed the recent developments, among them the growing popularity in public parlance of the diction of decolonisation on the one hand, and the global embrace of symbolic gestures such as the International Mother Language Day, in our context obviously attest to the correctness of Ngugi’s position on the necessity to use our languages in writing our literatures.

However, while the debate on the importance of indigenous languages seems to have been won, the actual prospects of using those languages in our life and society seem to be bleak, for the tragic reasons that our languages are dying.

Onslaught of the English language

In Kenya at least, the not so slow death of our mother languages is widely due to the relentless onslaught of the English language and its values, most of which have been problematically packaged as markers of sophistication, proof of education, and prerequisites for employability.

Pushed to the fringes of everyday usage, our mother languages are dying every day an elder dies, and remain precariously suspended on the works and wishes of a few academics keen on keeping them alive, perhaps because only such academics know and appreciate the reality that without our languages, we can never be respected elsewhere.

But these efforts are paltry and practically ineffective, especially in a society such as ours where policy makers and the political leadership are both inept and determinedly anti-intellectual. One would imagine that any sensible leaders would make long-term, favourable decisions, based on available credible information. Alas! Things do not work this way in Kenya.

Clouded in a rhetoric that perceives the humanities as some deadweight on their journeys towards ‘progress’, these leaders remain stuck in a grove of ignorance about the frightening prospects that our mother languages are dying, and that with these deaths the very agenda of ‘progress’ will amount to nothing.

Yet, our seasoned scholars have expressed themselves clearly. Kenyan critic at Princeton University, Simon Gikandi, has written a telling article entitled “The Fragility of Languages.” Citing UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, Gikandi notes that “forty three percent of the estimated 6,000 languages spoken in the world after 1950 are endangered, that 576 are critically endangered, that 528 are severely endangered, and that 231 are extinct.”

Elsewhere, renowned linguist David Crystal argues that by the end of the 21st Century, half of all the languages we speak today will be extinct, because “there is a language dying out somewhere in the world every two weeks or so.”

I can imagine that for our notoriously inward-looking policy makers within and beyond the academia, these grim facts do not mean much, despite them being a worrisome reality for the UNESCO fraternity that initiated the International Mother Language Day.

Future of mother languages

Curious to find out what the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development thinks about this challenge, I spoke to the Director, Prof Ochieng’ Ong’ondo. For the good professor, the institute has recently secured some funding from the World Bank to support some projects on literacy in marginalised languages, improvement of teacher competency and so on. Yet, his airy eloquence notwithstanding, the future of mother languages in our school curriculum and therefore in our literary staple, is still a wait-and-see scenario, given the previous neglect and the enormity of current challenges.

Even the controversial CBC now being rolled out is unlikely to inject new life into the thinning of our mother languages, and indeed spells doom for creative writing in our languages in future, especially if we agree with critics who argue that the system is inclined more towards vocational rather that critical aspects of learning.

From my experience, speaking to our policy makers in the only national curriculum institution in Kenya leaves one with a nearly overwhelming sense of despair about the current state and future of mother languages in Kenya. How would one explain the fact that the KICD, working with its parent ministry, has been procuring CBC textbooks in all subjects for all learners, yet none in our rich indigenous languages?

The revived National Language Policy in Education that was formulated back in 1964 is yet to be fully implemented because of inadequate technical and financial resources; content in indigenous language only exists in 23 out of the required 85 language variations, and even then, only for the first three years of formal schooling. Worse, only eighteen of our languages have an established orthography for future generations that may wish to write literature in mother languages.

Ultimately, the cold and hard reality is that KICD, like its parent ministry, needs to do much more to support the teaching of indigenous languages.

This calls for a collaborative networking with other entities in the same sector, notably universities, the parent and line ministries, with the help of experts, to ensure that our mother languages are rescued from the grim prospects of death that Gikandi worries about in the article I refer to above. The collaboration that I have in mind of course should transcend the junketing that often plays out in news or academic conferences that hardly have any follow-ups.

If there is any valuable message that we should harvest from UNESCO’s designation of an International Mother Language Day last Monday, therefore, it is that mother languages are fragile resources; that our civilisations and belonging to the world as a people all rest on the lives and longevities of our mother languages, and that as resources, “languages are more threatened than birds and mammals”, in the words of eminent ecologist William Sutherland. The future of our literatures relies on the salvation of our mother languages today.

This in turn depends entirely on what curriculum developers at KICD, policy makers at the parent ministry and across the education value chain do today.

The writer teaches Literature at the University of Nairobi